Elsa (Idina Menzel) from Frozen belts out a strong mezzo-soprano. Her sister, Anna (Kristen Bell), is a light soprano. The deceptive Hans (Santino Fontana) has a clear baritone. When Olaf the snowman (Josh Gad) starts singing, he’s a definite tenor. We don’t live in Arendelle, but these are a snapshot of the many voice types out there in our world.

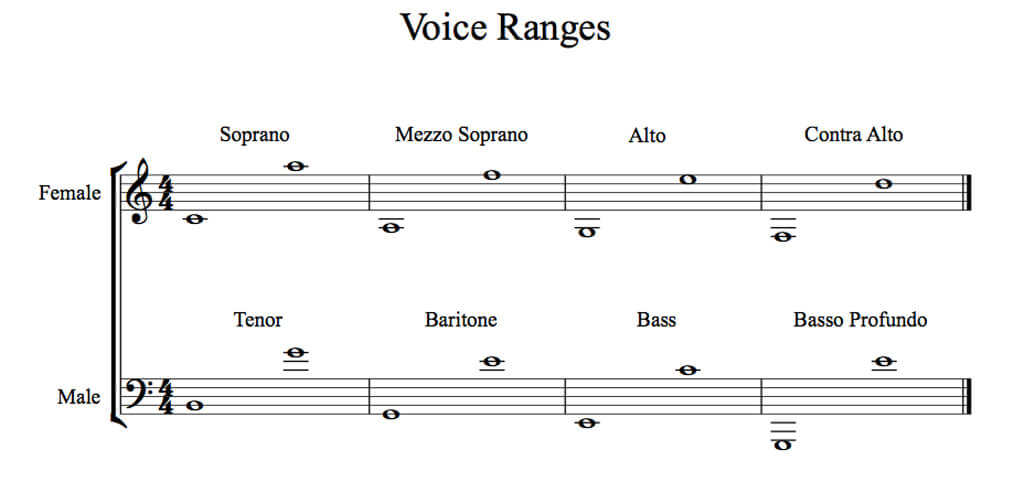

The human voice is arbitrarily sorted into “types” that are based on frequencies or pitches that the voice can sing. In the choral world, there are four main voice types, soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. These make up the texture of most choral works. These voice types typically correspond to specific frequencies. Additionally, most choirs are broken up in each section in case compositions require additional voicings. These are usually denoted, Soprano 1, Soprano 2, Alto 1, Alto 2, and so on. See the chart below for general reference:

The arbitrary part is that one is not limited to singing just in the range the notes attributed to their voice type. You’ll find baritones who can sing well into the tenor range and sopranos who have a strong alto range. Throw in falsettos, whistle tones, and chest voice, and you get a whole whack of range that can be developed and nurtured to produce sounds to fit any number of aesthetics or compositions.

University of Toronto Professor of Voice Studies, Darryl Edwards, provides some insight. He says “The quality of singer’s timbre at various points in their range, their confidence level, their vibrato, and their capacity to sing at various dynamics — these are all factors in determining placement. They also vary depending on the person from day-to-day, situation to situation. To quote vocal pedagogue Richard Miller in referring to vocal technique, singer placement involves both “system and art.”

Last year I was re-auditioning for the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, an annual process for every singer in the choir. I sang a medium-ranged piece that featured a few high notes to show off my tenor. I was surprised that our conductor wanted to place me into the baritones, feeling my voice was suited for that section. I understand why. I have a wide range and a solid tenor. My tessitura, or most comfortable singing range, is wider and lower than a lot of tenors. In any case, I have sung tenor in every choir since my voice changed. I protested and displayed my range through some scales and exercises and was kept in the tenors, much to my pleasure. Voice types are not always straightforward.

The Dimensions of the Voice

There are several dimensions that shape voice. Think about a male coworker, does his laugh boom across the office? What about a female co-worker in the lunchroom, does her voice rise above the din of the noise? All voices have different dimensions: Weight is how a voice fills space like the width and depth of Christina Aguilera or Britney Spear’s light soprano. Range is what pitches the voice can hit, the low ones a man or high ones a girl can hit. Timbre, or colour, is how we distinguish the sound; how the same pitch sung by two people will sound different even if it is the exact same note. There are many others like intensity, vibrato, age, and registration.

Professor Hilary Apfelstadt, Director of Choral Programs at the University of Toronto had this to say: “it is helpful to use colour as a determination of voice placement, as we do with sopranos at auditions when we hear more depth or richness and have them sing [soprano 2]. I like a pyramid with more sound and richness on the bottom and more lightness on the top.” This is a common goal of choristers and singers, to have a strong, solid tonality supported by upper harmonics.

Most often, choral directors are looking for a specific sound and will find voices to match that. Professor Edwards notes the “aesthetics modelled by Stephen Cleobury’s King’s College Choir, John Eliot Gardiner’s Monteverdi Choir, Eric Ericson’s Swedish Radio Choir or Joseph Flummerfelt’s New York Choral Artists.” These are all very distinct, different choirs with specific voices assembled to create a specific sound.

“Some singers are better at singing sixteenth notes than half notes, while others can do both,” says Professor Edwards. “Some singers can sing with absolutely straight tones, while others cannot or prefer not to. Others have rich timbres with pleasing vibrato, too. A discerning conductor can select singers who hold as many of the required skill sets as possible”.

The Diversity of Vocal Production

The added dimension in a great city like Toronto is that vocal production, physiologically, varies depending on what other languages you speak. Native Mandarin speakers are used to creating sounds that are produced in the middle towards the back of the oral cavity. Speakers of Swedish are much more forward in the oral cavity. English speakers find it difficult to produce Arabic tones because of their pharyngeal origins. This all impacts the way one’s voice produces sound.

Even in English, native Scots have a brighter texture to their voices than the darker shape of the south-west like Devoners (Think Professor McGonagall vs. Hagrid); yet both are the same English. Mandarin and Cantonese speakers have a very hard time producing sounds involving the sounds of the letter “L” (IPA: l). English speakers cannot easily create the sounds of the Arabic letter غ(ghayn). The deep, elongated vowels of Italian are hard for native English speakers to replicate subconsciously.

Just as some people will always have accents, but can speak without them, it affects the singing voice as well. I myself, am a cultural hybrid of Chinese Jamaican descent. Take the word “tree”. Say it while smiling, that’s more like the Canadian way. Now say it while frowning, and that’s more like the Jamaican way. Sing it to a pitch in both ways, and you end up with two very different sounds and textures. I’ve spent most of my life singing enough to know that no one ever wants “tree” sung the Jamaican way.

It is not just about articulators, or the ways we shape sound with our tongue, teeth, lips, and more, but about the fundamental difference in the way we produce sound using our full vocal apparatus. For newcomers to Canada, this is just another dimension in singing to navigate, and one that many vocal teachers are woefully incapable of addressing or even acknowledging.

The Changing Voice

Another key aspect of the voice is aging. Like any set of muscles in the body, the voice changes with time, and this can change the way our voices sound. Professor Victoria Meredith at Western University has advocated for all singers, but especially, aging adult singers to treat their voices differently. Much like one would not play soccer the same at age 12, v age 24, v age 62, it doesn’t mean that you can’t sing or play soccer, but you have to do it differently.

Physiology changes with age and Meredith provides hope to rejuvenate and reinvigorate the ageing voice. She takes elements of exercise physiology and applies them to the singer’s voice. Taken together, her approach calls for a holistic approach to the voice and the treatment of the voice apparatus as a full set of muscles that require exercise, toning, and health.

Chances are, as I age, I might find my voice moving into a more baritone range. I could even lose access to the higher or lower notes of my range. You might find that singing in alto has your voice feeling raspy and weary at the end of rehearsal. You might find that singing that soprano top “A” once or twice is okay, but not consistently for a five-concert run.

The best piece of advice comes from Victoria Meredith: “Comfort is your best guide… One of the challenges of voice building is that much of the time we cannot feel the parts of the body that are working. We can, however, feel if there is discomfort” (Meredith, 2008 p 56). Pay attention to the way you feel while you are singing — don’t hurt yourself.

“Our vocal abilities glide through various phases, and so does the maturity of our meaningful connections to our singing. Framing a change as an opportunity rather than a demotion is imperative. It’s just a change, and an invitation to a new dance. To be singing — that’s the thing!,” says Professor Edwards. He’s right. A good vocal teacher can help you on the path to a long singing career producing the best qualities of your voice at any phase and any age. However, sometimes you just gotta belt out “Let it go” at the top of your lungs. That’s okay; as long as you remember vocal rest when you get out of the shower.

References and more information:

Professor Darryl Edward’s blog and personal website.

Professor Hilary Apfelstadt’sUniversity of Toronto website.

Meredith, Victoria. (2008). Sing better as you age: A comprehensive guide for adult choral singers. Santa Barbara, California, Santa Barbara Music Publishing Inc.

For more CLASSICAL 101, see HERE.

LUDWIG VAN TORONTO

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.