National Ballet presents Rubies, Four Temperaments, and Alexander Ekman’s Cacti.

National Ballet of Canada. Choreography by George Balanchine and Alexander Ekman. Runs through March 13 at the Four Seasons Centre, 145 Queen St. W.; national.ballet.ca

The National Ballet of Canada unveiled its springtime ballet grab-bag Wednesday night, consisting of two well-known Balanchine neo-classical works, The Four Temperaments and Rubies, followed by a third, substantially more prickly piece by the prolific Alexander Ekman, titled Cacti.

But first, to the Balanchine duo that smartly led off the evening with such aplomb and chiseled beauty, celebrating the triumph of plotlessness central to the rise of twentieth-century ballet. Even though Balanchine was at the centre of it all, composer Igor Stravinsky came along first, with his neo-Classical re-purposing of rhythm that infused bold revitalization into dance, using asymmetrical metres that readily transferred to movement. From this early collaboration in the mid-1920s would come (eventually) the first plotless Balanchine ballet, Apollo.

Fast forward some twenty years and we come to The Four Temperaments (1946), a theme and four tropes on the ancient bodily humours, the National Ballet’s first offering of the evening. Balanchine seized on the conceit to make the melancholic, sanguine, phlegmatic and choleric representative samples of what amounted to being four new method snapshots of dance technique. It was quite an accomplishment to move to extreme distortions of form beyond anything seen up until that point in dance history, nothing less than a brilliant inversion of, albeit still based on, the earlier archetypes found in classical forms.

The driver of it all was not the plot but once again, rhythm. Except here, the composer was Paul Hindemith, who scored a brilliantly economical theme and variations for piano and strings, lending a perfect sound world that could at once encompass the odd-angled jerkiness of the choreography while still retaining smoothness of musical and balletic line. The paradox of tension and broken classical form, conveyed with a cool precision, as if to distance the art from the viewer was a device old enough and certainly well established, but it took special skills that were wholly unique to Balanchine’s company during the post-war period to bring off the odd turns on pointe, ungainly hip thrusts and seemingly strange arm extensions.

And the National Ballet performed it all perfectly in step, from Evan McKie’s natural Phlegmatic solo to the Sanguinic compulsive pair of Svetlana Lunkina and Naoya Ebe. Mr. McKie’s solo stayed firmly in mind after the evening was over, a model of beauty in line, his every move captivating. But the Lunkina/Ebe duo captured the fire of their Temperament while distancing me from them, remaining consistent with the demands of neo-Classical objectivity. Their turns and angles animated like a painting abruptly come to life, then froze once more into inward reflection. It was masterful movement, never showy nor too clinical, and always lovely. It made a lasting impression.

And Alexandra MacDonald’s splendid debut in the Choleric fourth variation was so perfect in its timing and in character with Hindemith’s Gebrauchsmusik (music for an occasion) that she made my evening. Dancing to Hindemith is difficult for anyone, but to make it look like the instrumental nature of the music was made to be danced to, in addition to making every outwardly awkward thrust and gesture of that balletic language cohere, was truly satisfying. She was the very meaning of Choleric – isolated, repelling, conflicted, paradoxical – like the musical score and the beautiful movement vocabulary they were conveying. These were my favourite performances of the night.

With Stravinsky’s neo-Classical potboiler Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra (1929), Balanchine found another piece for his later reactionary work Rubies, taken from his 1967 trilogy Jewels. Once again, the rhythm was, itself, the plot device, and featured the unconventional use of line and counter-line, whether off-angle or in counterbalance to something unconventional, and often coming with frequent extension and apposition — important tools to match Stravinsky’s metrically modulated, off-kiltered score.

If The Four Temperaments was a reaction to the war and a culture of experimentation in general, then Rubies, a kind of paean to American dance and pop/jazz fusions, was a reaction of substance to sixties youth culture. Rubies is the most ironic and angular of the three, daring in its hip thrusts and total unconventionality of rhythmic depiction via Stravinsky’s oddish syncopations, highlighted especially well in Pamela Reimer’s excellent piano playing.

And, the company gave the work a near-perfect performance, capturing the essential playfulness Balanchine’s work is meant to convey. Rubies is, after all, supposed to be a whimsical capriccio you can smile to while you dance, and Heather Ogden and Guillaume Côté were note-perfect throughout in their timing to the music. It is a pure pleasure to see such synchrony danced to music that conveys, in mechanics and aesthetics, the very opposite nature of what it seems to asymmetrically intend

Xiao Nan Yu’s Tall Woman was elegant and dignified, and the unconventional three-man partnering, holding her arm and leg in remarkable extensions amid an added ankle grab was amusing and supplicating, yet all at once oddly sublime in stage composition, especially with everyone clad in lush ruby-red costume.

Act III took us from the sublime to the surreal. Cacti seemed to be all anyone could talk about outside the Four Seasons Centre after the show, with the general consensus from the majority of the opening night crowd being that it was a wicked good time.

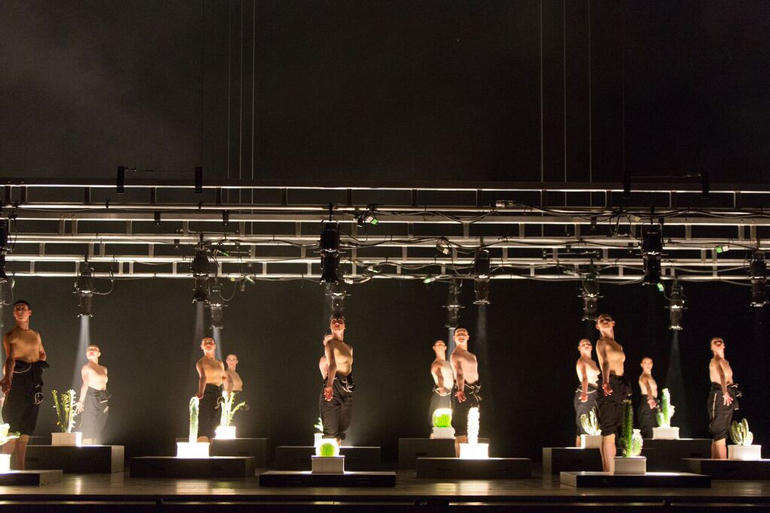

Sixteen dancers are placed on large portable white tiles which can take various configurations throughout the show. They move intensely, run on the spot, shout, pose, flex, mug, slap and stare in mock awkwardness. A string quartet plays upstage and meanders through the set. Later, a duo is sent up in relentless satire as we are taken inside their thoughts to find out they are really thinking about very little of anything at all, while executing demanding poses and smoke-and-mirror postures. Unusually stilted, obsequiously formulated academic language is voiced over from above in several other scenes, highlighting the frequent ludicrousness of critical response.

Cacti finally make their surreal appearance. It’s very sixties, from a time far back when navel-gazing art works probed questions about the nature of their medium and how reception to contemporary art could even be formed.

Mr. Ekman clearly thinks it remains important to ask these questions, but he makes it hard to sympathize with his disillusionment. For musicians, Mr. Ekman’s Cacti might be reminiscent of many works by John Cage, but without his gentleness of spirit.

Mr. Ekman’s deliberate, vacuously inane humour is served up with a sledgehammer, smashing against a world-view of a contemporary dance universe he finds inaccessible and boring, and equally excoriates its critics with vapid satire, a purposive playing on his perceived emptiness of the entire arts commons.

Cacti is supposed to be a thought-neutralizing work, and is ultimately successful on that account, judging from audience responses. Don’t think too much about Cacti, Mr. Ekman seems to be saying. Just watch It, have some fun, and enjoy the fact that, much like the intent behind the title, Mr. Ekman enjoys his role of playing prick while poking fun at everyone in the dance kingdom, from choreographers to dancers to, well, everyone else.

Everyone, that is, except his audience, whom he brings in on the joke. Go and see it for yourselves, and react. That’s all there is to know, and all you need to know.

Much like watching Balanchine, it is very often enough to experience and appreciate a lot of dance on its own terms, enjoying it simply for what it is.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Get our exclusive newsletter here and follow us on Facebook for all the latest.

- SCRUTINY | Opera Atelier’s Film Of Handel’s ‘The Resurrection’ A Stylish And Dramatic Triumph - May 28, 2021

- HOT TAKE | James Ehnes And Stewart Goodyear Set The Virtual Standard For Beethoven 250 - December 15, 2020

- SCRUTINY | Against the Grain’s ‘Messiah/Complex’ Finds A Radical Strength - December 14, 2020