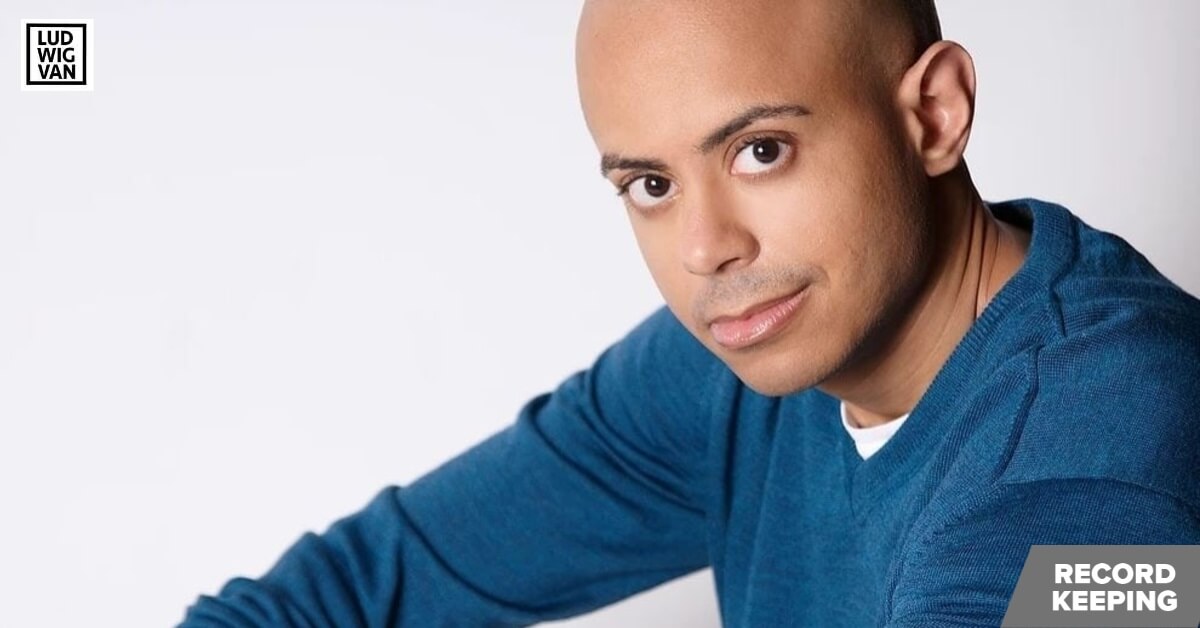

RECORD KEEPING | Stewart Goodyear Offers Pristine Technique And Sensitive Interpretation Of Beethoven Concertos

By Anya Wassenberg on September 17, 2020

Stewart Goodyear has always worn his heart on his sleeve when it comes to Beethoven, and his love of the material emerges as a technically polished and musically graceful interpretation of all five piano concertos on Beethoven: The Complete Piano Concertos, an Orchid Classics release.

(Continue reading)