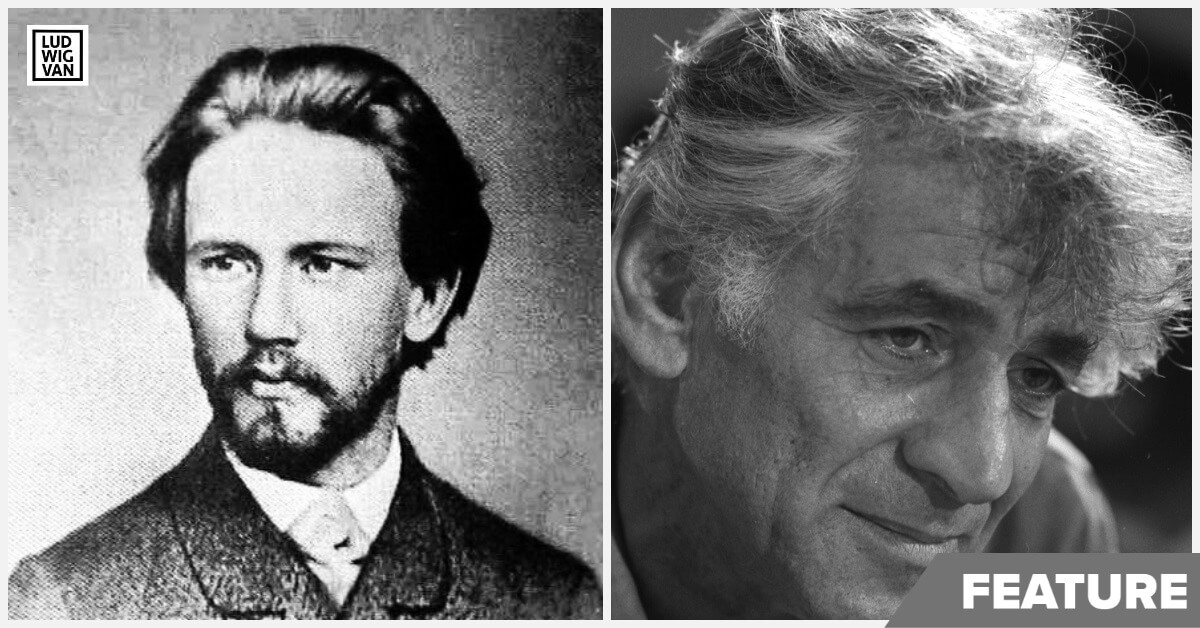

To honour Pride Month, LVT spotlights two illuminating presentations on iconic gay composers Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Leonard Bernstein.

Of the many summer events cancelled due to COVID-19, this year’s Pride Parade is especially regrettable. June 28 is the 50th anniversary of the first Gay Pride March, which took place in New York City in 1970. More of a protest than a celebration, it occurred a year to the day after the history-making Stonewall Riots, and was every bit as daring and radical an event as the uprising the year before.

But, if there is one community that understands the importance of staying safe where a virus is concerned, it is LGBT2Q+, which has survived and continues to live with the devastating virulence of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. COVID-19 is not a sexually transmitted disease, but it hampers all forms of human contact and is cruelly depriving. This is a moment for everyone, whatever their sexual orientation, to acknowledge how diminished life is when touch, closeness and affection is risky and unsafe, whether due to oppression or infection.

The soul-murdering effect of homosexual repression is one theme examined by psychiatrist and concert pianist Richard Kogan in his unique concert-lectures on the minds and music of great composers. In these masterful presentations, the Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical Center and artistic director of the Weill Cornell Music and Medicine Program offers a psychiatric assessment of the mental and emotional states of great composers and how they interplay (no pun intended) with their composition.

Kogan weaves virtuoso performances of illustrative masterworks throughout the presentation to illuminate his subjects. Since I first attended his presentation on Chopin at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting in Toronto in 2015, Kogan has broadened my perspective on many other composers, including George Gershwin, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Robert Schumann and Scott Joplin.

Kogan’s concert-lectures on Leonard Bernstein and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky both touch on the impact of homosexuality on their minds and music.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Kogan always acknowledges that any psychiatric diagnoses he applies to a historical figure is speculative, and only serves as a portal into the psychic state of the individual, as seen from the current state of psychiatry. With this caveat, Kogan is confident that today Tchaikovsky would receive a diagnosis of a depressive mood disorder, based on the frequent references in his letters and diaries to depression, as well as at least one suicide attempt. To Kogan there’s no question that Tchaikovsky’s sexual orientation was a major contributor (though not the only one) to his tormented state.

“Tchaikovsky experienced unremitting self-loathing about his homosexuality,” Kogan stated, quoting the composer, who wrote, “I think of nothing but ridding myself of his pernicious passion.” Beyond that, points out Kogan, during Tchaikovsky’s lifetime homosexuality was a criminal offence in Russia, punishable by deportation to Siberia as well as complete loss of civil rights, condemning all homosexuals to exist in a mentally-corrosive state of fear. For Tchaikovsky matters were made worse by his attraction to males in early adolescence. In 1869, when he was 29, the object of his desire was a 15-year-old conservatory student whose suicide intensified Tchaikovsky’s resolve to become heterosexual.

The turmoil and yearning of this episode of prohibited love is clearly expressed in the music Tchaikovsky composed during this crisis, the Fantasy Overture Romeo and Juliet. Kogan demonstrates that Tchaikovsky used music to cope with his prohibited desires in his presentation when he plays the sublime theme from Romeo and Juliet, suggesting that this young man, “is almost certainly the inspiration for that theme.” (Have a look at about 7:50 in the video below.) The parallel suffering of Romeo and Juliet and the composer himself that can be heard in this theme is a powerful illustration of Tchaikovsky’s assertion that, “without music I would go insane”.

Mental health depends, in part, in the ability to bring intolerably intense emotions down to a manageable level. The more ways an individual has to do this, the easier emotional life will be. According to Kogan, Tchaikovsky’s difficulty attaining moderate emotional states is clearly seen in a composition such as his first piano concerto, excerpts of which Kogan performs in his concert. “The majestic opening theme of the first movement never comes back, which is unprecedented,” explains Kogan. “Tchaikovsky sought to escape into idealized musical fantasy worlds, full of excess and extravagant gestures because his despair was so urgent. What could be more extravagant than writing a glorious opening theme and then just tossing it away?”(See 13:30 in the video below.)

In 1877 Tchaikovsky attempted to achieve a semblance of normalcy by getting married, a disaster that culminated after 9 weeks in a suicide attempt. The psychiatrist he consulted in the aftermath of his staged faux-drowning prescribed total lifelong avoidance of his wife. The rest of his life Tchaikovsky was terrified that his estranged wife would expose his homosexuality.

From that point forward Tchaikovsky flourished artistically, musically and financially at the same time as he deteriorated psychologically and emotionally. The triumph of conducting the 1812 Overture at the opening concert of Carnegie Hall in New York in 1891 was not enough to temper his alcoholism, chain-smoking and chronic stress. When he was 51, he was ravaged by another agonizing infatuation towards his 14-year-old nephew, to whom he dedicated his Pathétique Symphony (no.6). His death 9 days after its debut, ostensibly from drinking contaminated water, may have been a suicidal ingestion of poison intended to prevent exposure of his sexual activities. The final phrases of the Pathétique, which Kogan hears as, “the most eloquent suicide note ever written,” lend credence to the possibility that Tchaikovsky took his own life. (See about the 27-minute mark in the video.)

Had Tchaikovsky lived in an era of equal rights for homosexuals, he would have experienced less fear and shame and more dignity. He might have found stable and lasting love. How would this have been expressed in his music? This fragment from a letter to his patroness suggests an answer:

“I repeatedly try to express in my music the torments and bliss of love,” Tchaikovsky wrote. In a more liberated time, there might have been more bliss and less torment in his music.

Leonard Bernstein

In a sense, Tchaikovsky’s depressive personality was the outcome of emotional malnutrition due to a shortage of familial and romantic love. By contrast, Leonard Bernstein’s ebullient and joyful character was nourished by an overabundance of every flavour of love, from maternal to collegial to romantic to erotic. Kogan sees Bernstein as an example of a hyperthymic temperament, an uncommon disposition that seems to be hardwired for happiness, but carries with it the risk of an extreme plunge because the high baseline mood state can fall precipitously if it is destabilized, and has no experience of an intermediate neutral mood.

Homosexuality was still criminalized in America during Bernstein’s youth. It was also considered to be a mental illness by the field of psychiatry, which prescribed reparative therapy to re-orient homosexuals to heterosexuality. The pervasive stigma and discrimination towards homosexuals, which made it necessary for many if not most gay men to adopt a public stance of heterosexuality, consigned those men to inauthentic lives and conflicted internal states.

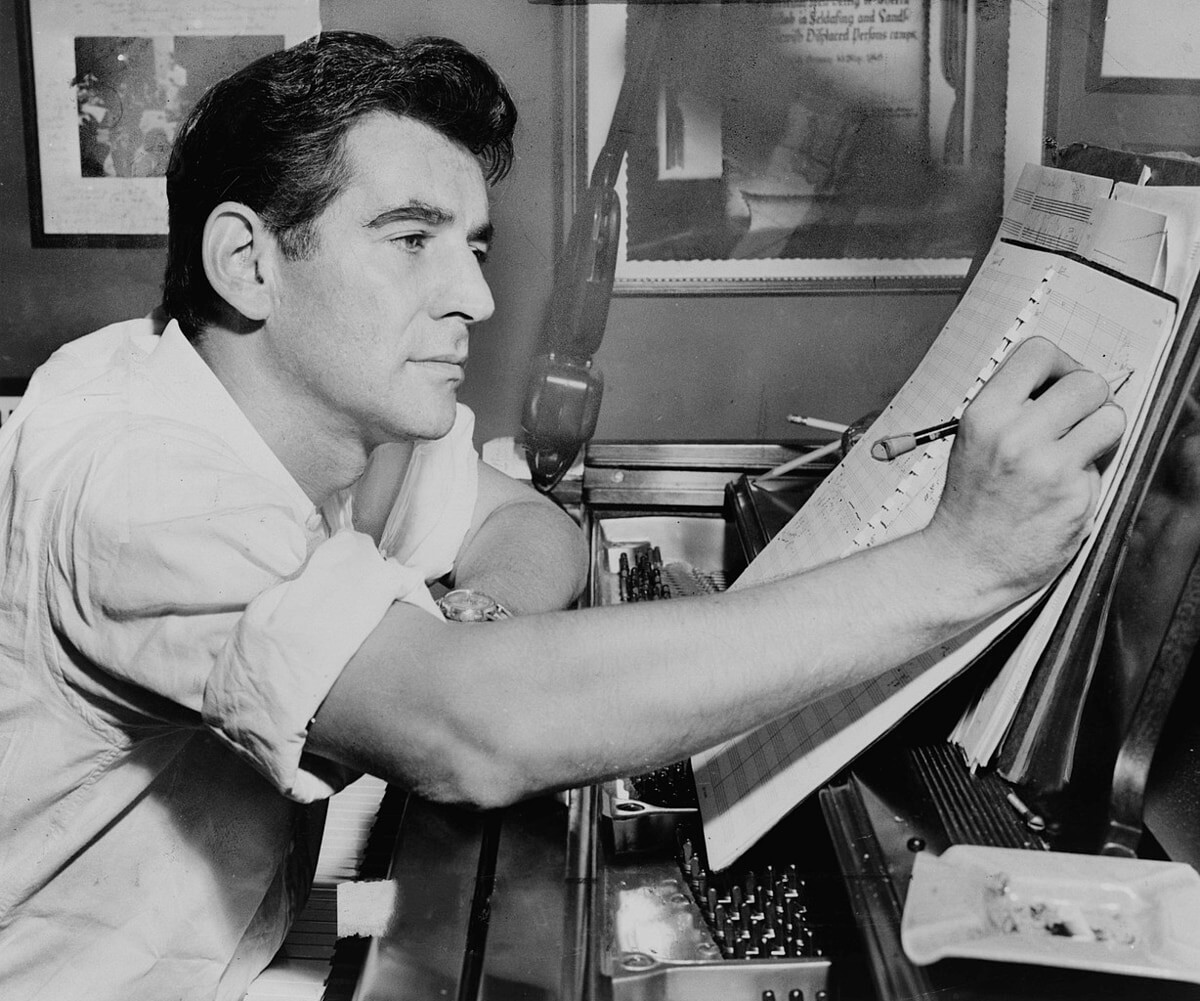

This was true for Bernstein for most of his adult life. Advised that to attain a conductor’s podium, he would have to assume a heterosexual public persona and dispel any suspicion that he was gay, Bernstein married in 1951. The marriage, which lasted 25 years and produced three children, did not re-orient Bernstein’s sexuality. It did, however, provide the veneer of heterosexuality, a secure emotional base and a stable modus vivendi that allowed him to develop a career as a composer, conductor, concert pianist, and music educator that was so prodigious that Kogan describes him as, “the greatest all round musician America has ever produced.”

The stability of this way of life was dramatically disrupted with the radical shift in attitudes and emerging acceptance of homosexuality ushered in by the Stonewall Riots in 1969. In 1972, at the urging of his psychiatrist, Bernstein left his marriage to live openly with a male lover 40 years his junior. It was no longer necessary for Bernstein to pose as straight to protect his reputation or his career, but there was a high emotional price to be paid for leaving his family. His remaining years, though still hyper-productive in nearly mythic proportions, in terms of conducting, broadcasting, teaching and recording, were darkened by depression. He suffered from a sense of failure as a serious classical composer, and experienced profound guilt over leaving his wife, convinced that this caused her death from cancer.

Given his conflicting intense desires and appetites, complex personality and seemingly limitless and multi-faceted talents, Kogan believes Bernstein used music to regulate himself extremely well. His multi-focal pursuits rather than a single focus on classical composing were essential to harnessing his overpowering drives.

“As a performer he could be flamboyant and receive the adulation on which he thrived; as a conductor, he could achieve ecstatic states and release physical energy, as a serious classical composer he could attain the moral gravitas he felt was incumbent upon him, and as a teacher he could emulate his learned father’s Talmudic prowess and also inspire students with his ardent vision of music as a universal, shared language that he believed could bring world peace.”

Bernstein recognized that music was central to his psychic survival. “Music has saved my life,” he once said.

Simply put, persecution is bad for mental health, whether perpetrated by the State, the employer, the faith group, the schoolyard clique, the family or the community. At the same time, outwitting the oppressor in order to survive produces ingenuity and creativity that can be richly expressive in music and other art forms. Kogan points out that Tchaikovsky and Bernstein each set the beloved story of prohibited love — Romeo and Juliet — to music and each contain oblique musical references to forbidden passion.

The love presented in Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture never reaches a state of consummated passion, but remains at a level of unfulfilled and unending yearning, expressing how inescapable the grip of a powerful attachment can be. Bernstein’s compositional representation of love in West Side Story is edgier, capturing risk and unpredictability. His continuous use of the of the tritone, an unstable interval of irresolution, that was once referred to as “The Devil’s Interval” and was banned by the Catholic Church, can be heard as a subversive refrain. Even Tony’s ardent love song, “Maria” begins with a tritone. But there is also anticipation, excitement and thrill, and a more overtly sensual edge in West Side Story, especially in the energetic rhythms and modern musical styles including Mambo and be-bop jazz.

West Side Story’s setting in mid-50s New York City also may have allowed veiled allusions to the need for gay men in America to pose as straight. Instead of the clergy-sanctioned, though secret marriage ceremony of Romeo and Juliet, as there is in Shakespeare’s version, Tony and Maria enact a symbolic wedding, entering into a pretend marriage, perhaps an oblique echo of the need for sham marriage as a protective camouflage used by Bernstein, and many other homosexuals, including Tchaikovsky. Some of West Side Story’s lyrics (co-written with Stephen Sondheim) allude to the repression of illegal but irresistible attraction, as in “I Have A Love”: When love comes so strong, there is no right or wrong.

“The four men who collaborated on West Side Story, Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, Arthur Laurents and Jerome Robbins, were all gay,” Kogan pointed out to me when we chatted about his two presentations. “In telling the story of Romeo and Juliet they could also tell the story of their experience of love in defiance of social norms. The hope for tolerance, safety and acceptance, is evident in the lyrics to Somewhere: there’s a place for us…a time and place for us…somehow, some time, somewhere”. Not that they agreed to write an anthem for the gay community, but their empathy for these characters would have been heightened by their own experience.”

Tchaikovsky and Bernstein both used their musical talents to protest tyranny and celebrate freedom. The 1812 Overture, which Tchaikovsky composed in 1880 to commemorate Russia’s defense against Napoleon is a favorite musical salute to independence to this day. Bernstein conducted Beethoven’s 9th Symphony in Berlin while the divided city’s residents were chiseling the detested Berlin Wall into pieces. Over 100 million people (including me) watched and listened to this epochal concert, thrilled to hear the word “Freiheit”— freedom — which Bernstein substituted for the original word, “Joy”, immortalizing the moment by transforming the Ode to Joy to the Ode to Freedom.

There’s no doubt that if they were alive today, Tchaikovsky and Bernstein would be applying their musical talents to the challenges faced by LBGTQ2+ communities and the world at large.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.