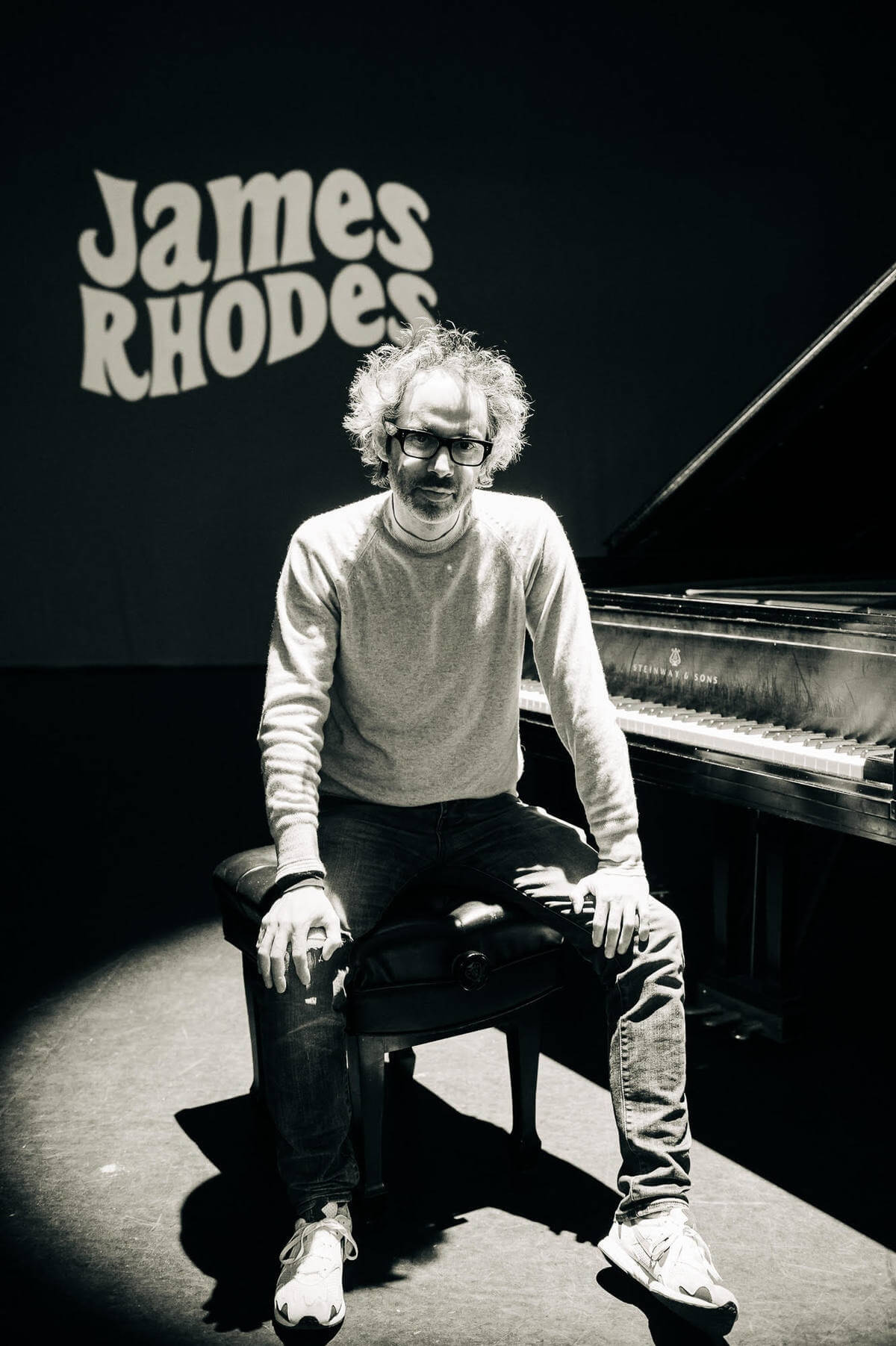

James Rhodes brings f-bombs, an irreverent approach, and sensitive and virtuosic interpretations of Beethoven’s lesser known piano sonatas in his Canadian debut.

The Glenn Gould Foundation: The Beethoven Revolution.; Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 15 in D Minor, op. 28 (“Pastoral”); Piano Sonata No. 27 in E Minor, op. 90; Piano Sonata No. 21 in C Major, op. 53 (“Waldstein”). James Rhodes, piano. Koerner Hall, March 5, 2020.

Why aren’t there more piano recitals like the one James Rhodes presented last night?

U.K.-born pianist James Rhodes has made a career out of making the genre less intimidating.

His Canadian debut at Koerner Hall on March 5, 2020 — at the invitation of the Glenn Gould Foundation — is an example of what the future of the genre could be with a bit less pomp and finery: exciting, at times dangerous, the kind of music you could listen to in a leather jacket.

Despite all the unwritten rules that can make classical music feel dated, the buck will always stop at the performer — and as long you’re playing the heck out of the piece, who gives a damn what else you do up there?

He’s not the first to strike out in that direction. In fact, there’s a growing list of eager ambassadors, who, when attempting to demystify the genre, lose audiences in the process. Not Rhodes. In a black knit shirt, faded black jeans, and running shoes, his performance nailed the cool millennial-concert-pianist aesthetic (though he’s not officially a millennial; he turns 45 today, happy birthday). He made the best of both worlds; his preambles were laced with f-bombs and sitcom references, but once he sat down at the piano, no amount of relatable banter could conceal his fervent devotion to his instrument.

The program, titled The Beethoven Revolution, was a selection of three of Beethoven’s lesser known piano sonatas, which Rhodes recorded nearly a decade ago. His entire performance was, without exception, a virtuosic mini-marathon of intricately braided musical material.

At times, his showmanship got in the way of exactitude, but the sincerity of his approach to performing is the hand that grabs you. It wasn’t just about trotting out slightly obscure works to celebrate Beethoven’s 250th birthday; everything about Rhodes’ musicianship suggests that he’s trying to find modern iterations of that thing the composer was originally looking for in his music.

Is that thing still alive? Is it compatible with profanity and the rest of our modern sensibilities, or is it the case, as Rhodes proudly declares, that “Classical music is not high art”? Do some performances need to be rough and rowdy in order to squeeze some life out of it?

The prognosis is of course not so bad. There’s an excess of life in the music, though it’s often stifled by the museum-air that one has to breath in order to get to it. That was one of the takeaways from his conversation with the Glenn Gould Foundation on March 4: “The problem with the classical music business is they keep saying they want young people, but they only really want rich white people.” Preach.

He also walks the walk as a multimedia advocate of bringing classical music back into pop-culture. His fourth book, JAMES RHODES’ PLAYLIST: The Rebels and Revolutionaries of Sound, was published last year, and he’s also churned out seven studio albums with such universally accessible titles like FUCK DIGITAL. Oh yes, Hollywood is making a film about his life, starring The Amazing Spider-Man’s Andrew Garfield.

Even when all of that is said and done, there’s still ample opportunity to drop the ball when you actually sit down to play — and this is where Rhodes is a head above like-minded ambassadors of the genre. His priority isn’t that you understand the music, he wants you to fall in love with it, let it save you as it once saved him. You can tell that from the heat that radiates from his interview answers, and how he does away with all those useless gestures — a la Lang Lang — that draw up smoke and mirrors where the unmistakable honesty of Beethoven’s musical dialect should otherwise shine.

Things got off to a very rocky start when he began the Pastoral Sonata (Op. 28 Piano Sonata No.15): they were the completely wrong notes. At least that seemed to be the case initially, until the collective realization set in that it was neither the Pastoral Sonata, nor was it Beethoven. Bach, in fact. Without a word of explanation, Rhodes opened his Beethoven recital with Bach’s Chorale Prelude for Organ (arranged for piano by Siloti), a gentle nod to the seminal composer and to his idol Glenn Gould.

It was business as usual when the Pastoral finally sprang from the keyboard, proof that you don’t need all that ceremony and ugly white bow ties to make Beethoven work. The sonata is a beautifully domestic kind of music, evocative of Beethoven’s ‘interiority’ as Rhodes put it. In this sense did Beethoven walk so that Satie and Debussy’s cozy parlour-music could run. These sonatas, however, emit an aura of studious solitude, amplified by Koerner Hall’s rustic and varnished surfaces and Rhodes’ natural delicacy. His handling of the fourth movement was especially telling, imbuing it with a nocturnal lucidity.

In his stage-banter for the next item on the program, Rhodes perhaps unknowingly added a bit of embellishment for the sake of a dramatic backdrop to the music. Making the oft repeated mistake of misattributing the subtitles of the two movements of the Piano Sonata No.27 (Op.90) to Beethoven, Rhodes described how the first movement is to be understood as a ‘Contest Between Head and Heart’ and the second as a ‘Conversation with the Beloved’. Those were subtitles forced upon the work by Beethoven biographer Anton Schindler, whose zeal for that particular interpretation went as far as forging the composer’s handwriting.

But, to fixate on such minor details would be to miss the ‘revolution’ Rhodes intended. His was a one-man assault against the rigid academism that’s always in the background of your typical night at the symphony. And it worked. For example, the contrast between the emphasis on the opening subject of the first movement and its markedly reserved repetition, carried a special meaning in light of it being a dialogue between a raging heart and a reasoning head.

A bit of background is needed to appreciate the gravity with which Rhodes arrived at the last item on the program, the so-called Waldstein Sonata (Op.53, Sonata No.21). Rhodes’ journey to becoming a concert pianist is unlike any I’ve ever encountered. Between the age of 18 and 28, he didn’t once touch a piano. And, before that, his formal musical education only began at the age of 14. Much of that absence was the result of debilitating injuries he suffered from being a victim of vicious sexual assault as a child. He fought through all of that to return to his passion at the piano as an adult.

The man is all kinds of strong, a strength he credits almost entirely to the influence of music, Bach and Gould in particular — literally being smuggled an iPod filled with music by those two while in a psychiatric ward. Though that particularly gruesome pain cannot be quantified and understood, his fervent belief in the healing power of music is a message that is infinitely relatable. A prolonged proximity to pain can cultivate an insatiable yearning for music, I believe, and to that end there is nothing comparable to the fervent gospel occasionally found in classical canon.

Before taking up the first movement of the Waldstein, Rhodes directed our attention to the very last note of the second movement, all of which is merely an introduction to the third movement. That third movement earned the Sonata the nickname of ‘Dawn’, which Rhodes attributed to a French origin (though it is in fact an Italian one, ‘L’Aurora’). After the fairly uproarious excursion of the second movement, the material arrives uninterrupted into the third. It’s the kind of cadence that relaxes muscles you didn’t even know were tense, and Rhodes’ touch could not have been more suited for that arrival — as if coming home to an innermost interior space; some lines from Derek Walcott’s poem “Love After Love” immediately rang in my ear.

Everything after that final note is Beethoven as he’s not often recognized: a melodist of robust and Romantic sensibilities. The whole third movement is indeed a kind of sunrise, a picture painted by Rhodes’s performance, finding radiance in cadence and consolation in a new beginning.

He followed it up with three encores — one too many by Toronto standards — but the reception could not have been warmer nor more grateful.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- THE REMOTE PODCAST | Conductor Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser On The Cultural Changes Taking Place In Orchestras - November 23, 2020

- THE REMOTE PODCAST | Catching Up With Tapestry Opera’s Savvy Artistic Director Michael Mori - November 6, 2020

- REMOTE | Diane Leung: ‘This Is The Time Where We Are Forced To Grow And Change’ - October 22, 2020