A canary in a coal mine for the current state of classical music and overcoming sexual abuse: A deep dive into the classical music phenomenon of James Rhodes.

One of television’s most fabulously contrarian moments comes with the “Bubble Boy” episode in the seventh show in the fourth season of Seinfeld.

Originally aired Oct.7, 1992, it has Jerry and the gang getting out-of-town to the peace of a lakeside cabin. Things go awry — stratospherically awry — when George and Susan, his girlfriend, as a good will gesture meet Donald the “bubble-boy”. Poor Donald. He’s condemned forever to live in an entirely sterile, insular, plastic-wrapped environment. (Wait. Don’t get out the handkerchiefs yet.) He soon proves to be a dork, an arrogant and socially inept jerk with a vile temper who becomes enraged during an innocent game of Trivial Pursuit and strangles George for daring to contradict an answer. You can almost hear a studio-audience cheer when Donald’s bubble deflates after being punctured by Susan, standing by her George.

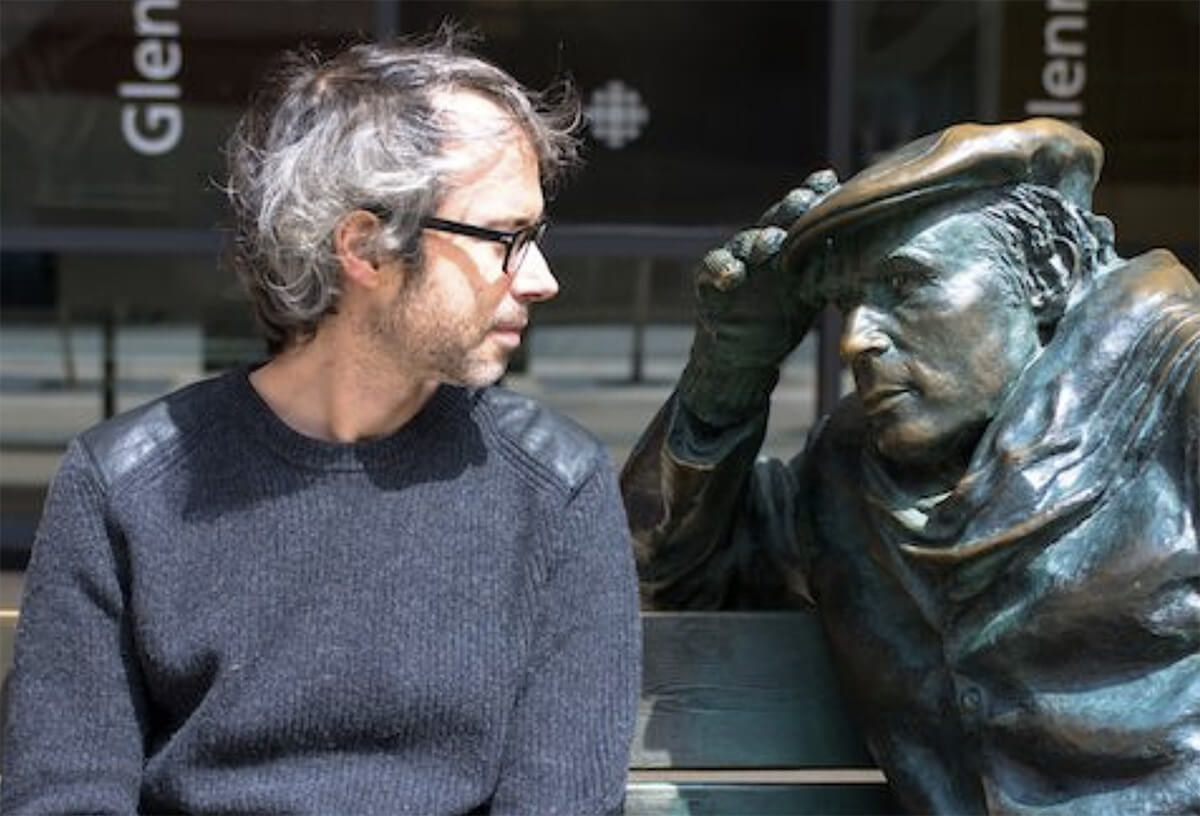

An unsympathetic bubble boy? What’s next? Well, we have the answer. James Rhodes, a crusty, cussing concert pianist, Glenn Gould fanatic and world-class politically incorrect maverick who’s bent on saving abused children and classical music. His virtuoso-level swearing may be muted, one assumes, when he appears at Koerner Hall with an all-Beethoven sonatas program for his March 5 Canadian debut. (He’s talking on March 4 at the Isabel Bader Theatre.)

Hold on. I just did it. I said, “one assumes.” I should have known better. Assuming anything about Rhodes doesn’t work except in assuming he’s going to get your attention one way or another. Just don’t assume how. Rhodes, now 44-years-old, is a force of raw nature. “Classical music makes me hard,” he insists. There you are. Any more questions?

However unapologetically incorrect Seinfeld seems in these apologetically correct times, the show’s over-the-top capabilities are minor league compared to how Rhodes reveals himself in interviews, as on CNN, or in print. James Rhodes: Instrumental: a Memoir of Madness, Medication and Music is his 2014 best-selling account of how, between the ages of six and 10, he was raped by his gym teacher. The revelations are equally horrific and breathtaking. “I left school at 18 feeling like 68,” he says, adding how he realized, “that the rest of my life could safely be spent destroying myself.” Elsewhere, he drops the bomb: “I have an urge to eviscerate myself.”

Disassociation is impossible because it’s “the most serious, and long-lasting of all the symptoms of abuse,” he writes.

Disassociation is impossible because it’s “the most serious, and long-lasting of all the symptoms of abuse,” he writes. “It’s really quite brilliant.” Here’s the blunt truth behind what started in that gym so long ago. It’s something a little kid would know for what it was and would never forget:

“He’s inside me and it hurts.”

Such language, style and facts so shocked Rhodes’ first wife that she tried to block the book’s publication, arguing that their son might forever be “psychologically harmed” by his father’s graphic revelations. The injunction against publication in England was eventually lifted by the Supreme Court in a decision cheered by abuse survivors.

It’s brilliant. It hurts. Die. Survive. Words in stark opposition to each other, ideas that clash, entire chapters which zoom off in different directions. Taken together they blow away any sense of comfort you want Rhodes to bring to his story. He never wants to let the anger go. His concert journal, Fire On All Sides — the title derives from stage directions in Mozart’s Don Giovanni — outlines the depression endured while living his touring concert pianist’s life. Music was a form of “spiritual salvation”, as he describes it to me.

Rhodes’ own efforts to demystify classical music led to a short-lived contract with Warner Brothers as the label’s first classical artist. (He left Warner, claiming the label took too long between releases). No matter, he intends to humanize — if that’s the word — the gods in the classical music Elysium. Bach, he’ll point out, had Mick Jagger’s appetite for women and “boned groupies” between fingering fugues. Rhodes even has his own line of T-shirts sporting composers’ names. Yet, he remains awestruck by the pianism of great players these days, and rhapsodizes about Evgeny Kissin and Barcelona soccer star Lionel Messi in the same sentence; (it comes down to their micro-movements.)

“But where else can we go and close our eyes without Twitter and Facebook than in a concert hall?”

He despairs about what’s evolving in the concert world. “There’s been such an emphasis on technique,” he tells me. “It seems to have polarized classical music so that it has to apologize for itself. These days going to a concert feels like going to a church. It shouldn’t. You shouldn’t need any knowledge at all. But where else can we go and close our eyes without Twitter and Facebook than in a concert hall? They have WiFi in planes now.

“I see a generation of kids leaving school who have no fucking idea of who Bach is or what a cello is. On the other side, you see other kids coming from a conservatory who, from the ages of six or seven, practice eight hours a day.”

Catching up to his back-and-forth mood swings can take him from being “incandescent with rage,” one moment to tear-drawing openness the next, as when he says, “Music is so enormous, it goes so much deeper than just that one word.” One moment, you want to hug him to drive away his devils. (He’s scruffy, skinny, and utterly needy-looking like a puppy brought in from the rain.) Another moment you feel so rattled by this emotional ping-pong game he’s playing, you long for doing something, anything more structured, like taking up martial arts.

He understands his effect. He’s not over-the-top about being over-the-top. “Victim is a trick word,” he tells me. “It has to me a very negative connotation. ‘Survivor’ may be a better word. One of the very serious problems of child abuse is that it happens when the brain is a sort of plastic and can be formed. (Abuse) can literally change the wiring of the brain in a way. It’s always going to be there. I am always going to have the capacity to wallow in self-pity.”

And — bloody hell — it works, this capacity to intellectually and emotionally light up the sky. Critical word may still be out on his playing of Beethoven. But Rhodes’ depth-charge like revelations have helped pave the way for the #metoo movement, and revelations about the transgressions of superstar musicians from conductor Charles Dutoit to James Levine to Placido Domingo. Rhodes’ revelations of abuse became part of the conversation around the conviction in 2013 of the ex-Director of Music of the Chetham music school in Manchester.

Rhodes’ anti-abuse campaign is taking root in Spain, since 2017 his adopted country — “Why? Brexit,” he sighs — where the left-leaning Socialist Party plans to enact as one of its first reforms as the so-called “Rhodes law.” (The thought of children having to defend themselves in front of their accusers told Rhodes how out-of-date was Spanish law.)

The truth is, I didn’t really get James Rhodes, and thought that maybe his super-aggressive, blow-it-all-up thinking was too over the top, no?

“No,” said Canadian violinist, Lara St. John, across the bistro table from me in the Boucherie on 7th Ave. in New York.

St. John’s own revelations about her abuse as a teenager at the hands of her violin professor, Jascha Brodsky, during her years as a student at Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute, were published late last year in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

St. John looked at me as if I was addled. “Put it this way,” she said over the din around us, “what he says is something I very definitely want to say. He just said it in a better way.”

She paused.

“Do you have his email address?” she asked. “We have to talk.”

—

James Rhodes makes his Canadian debut with an all-Beethoven program “The Beethoven Revolution” at Koerner Hall in Toronto, on March 5. He will also be giving a talk, “An Evening In Conversation with James Rhodes”, at Isabel Bader Theatre, on March 4.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- MAJOR CHORDS | Car Culture Meets The Orchestra At The Drive-In - October 7, 2020

- PROFILE | Max Richter: ‘The Pandemic Has Changed All Our Thinking’ - August 13, 2020

- INTERVIEW | François Girard Tells Us About His Unique Brand Of ‘Flying Dutchman’ For The Met Opera - February 29, 2020