We met director François Girard in New York, to talk about the Met Opera’s production of Wagner’s Die Fliegende Holländer, and the comparisons between film and opera.

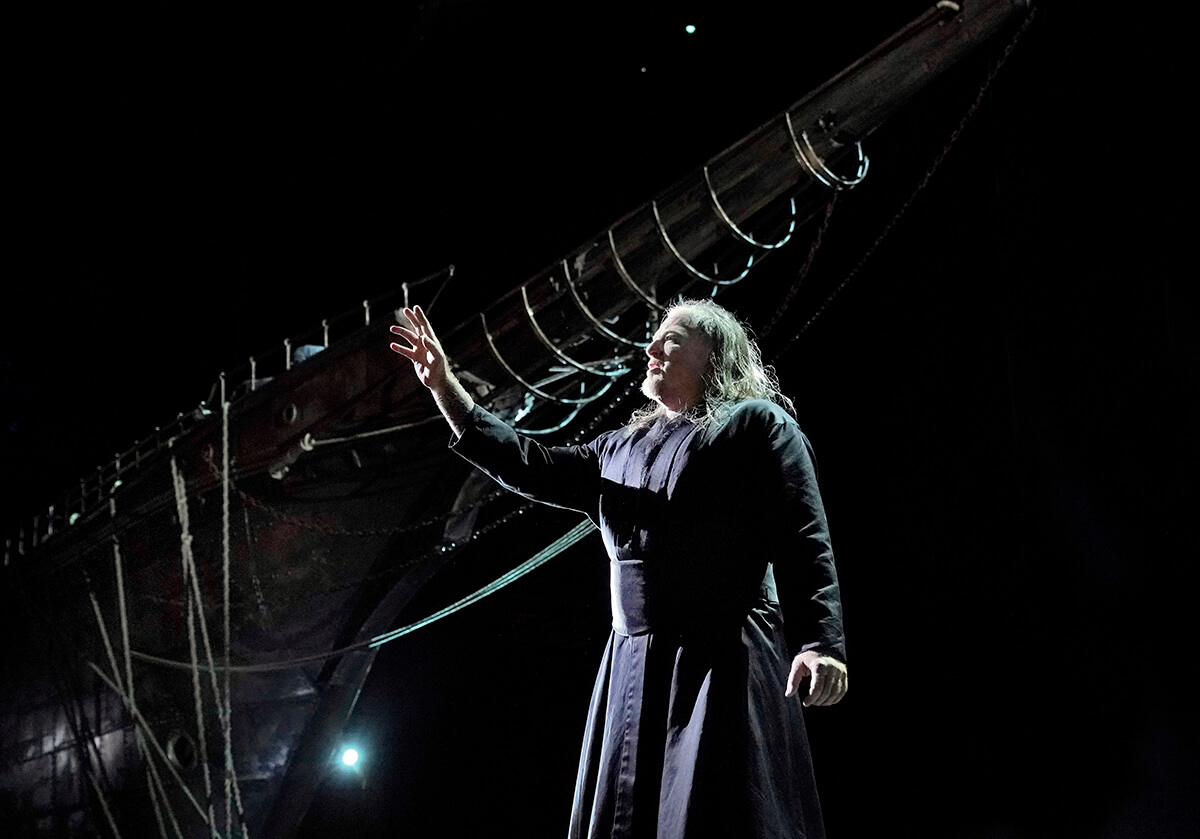

NEW YORK — It’s high noon when François Girard turns himself into a ghost. It makes sense, despite the early hour. It’s a good look for this wispy figure with sharp eyes peeping out beneath his head’s nest of thick, greying hair. (Imagine Scrooge — Alistair Sim — Lite.) The occasion is the midday break in rehearsals for the Metropolitan Opera’s new production of Wagner’s Die Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) for its March 2 opening. (It closes March 27). And when Girard darts up on the Lincoln Centre stage checking on this or that, he materializes in and out of the made-to-order Baltic mists that creep across John Macfarlane’s slate grey set.

Lincoln Centre itself feels a touch haunted these days. For starters, Sir Bryn Terfel, all set to sail again through his signature Dutchman role, cancelled his return to the company after an almost eight-year absence due to a fall, breaking an ankle in three places, and requiring surgery. His replacement. Evgeny Nikitin is the Russian bass-baritone and heavy-metal aficionado who, in disclaiming that his multiple tattoos suggested a swastika, withdrew from the 2012 Bayreuth Festival to put the issue to rest. (Nikitin, who had his Met debut in 2002, sang the Dutchman in the Canadian Opera Company’s 2010 production.) Questions of political correctness are rarely distant from anything Wagnerian. And Girard is particularly ungiving about this. “In my travels, I’ve been very well aware of the far right-wing rising,” says the 57-year-old Montréal-based director. “But I think you deal with what Wagner wrote.”

Then of course, there is the ghostly blob projected by some sort of new tech magic which mimics the Dutchman’s every move, conjuring up a spectre which might be scary to some, but to others might border on the Grand Guignol. Nicknamed “the shadow,” it’s not quite as creepy sounding as the Lamont Cranston “Shadow” on the Blue Coal Mystery Show on radio the ‘30s and ‘40s. To Girard’s mind though, the Dutchman himself is spectral, with one foot in reality, the other in the netherworld.

Girard himself is very real to Met management following his much-praised Parsifal of 2013 (a co-production with Opéra de Lyon), revived in 2018 for the Met. Even more fundamental is his long-standing relationship with Met director, Peter Gelb. During his days as head honcho at Sony Records, Gelb helped ensure the 1993 success of the Girard-directed Twenty-Two Short Films about Glenn Gould. In 1998, Gelb was behind The Red Violin, which earned composer John Corigliano a Best Original Score Oscar

“In my travels, I’ve been very well aware of the far right-wing rising. But I think you deal with what Wagner wrote.”

Gelb, an endlessly controversial figure in New York, was most recently pilloried for siding for too long with the disgraced Placido Domingo following accusations from 20 women of the singer’s predatory sexual transgressions. Gelb has also locked horns with the Met’s many unions while trimming staff. But, with the 2019-2020 season an unqualified hit — the Met’s run of its Porgy and Bess being extended — and Gelb’s contract re-upped to 2027, he will no doubt continue running the company as if it were the New York Yankees, with the rest of opera acting as its farm teams. “The Met is a repertory company,” Gelb told me a while back. “We had the (Festival d’opéra de Québec) as the test kitchen for the production (of the Dutchman, in the summer of 2019, for Girard’s first directed opera in Québec.) We have to make sure, as a new production, it can play with other productions.”

Gelb to World. This is the Met where even back, back rooms have star power like the alcove I came across dedicated to Sara and Richard Tucker, the beloved New York tenor, “by their sons.” Nikitin knows all about this. As soon as he got the call that Terfel was out, he dropped four appearances at St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre, and a pair of concert vision of Dutchman, one in Moscow, to free up time for the Met.

Speaking of the unreal, did I mention the pay telephone, a real deal, money-taking pay telephone, located just through the sequence of stage doors leading backstage passed the security guard, which Girard rushes past when he needs to go outside to have a smoke? It gives one pause, this blast-from-the past payphone with its beautiful, battered, chrome face, its spirit of critics using it to bellow at long-suffering night editors on the culture desk that they’re going to be filing late because, hey, with Wagner you’re always going to be filing late. Lincoln is all arch modern on the outside, but inside has a wonderfully worn feeling, like that payphone.

Die Fliegende Holländer is where Wagner discovered what it meant to be Wagner, clarifying — in his compositional practice and thinking — the concept of the leitmotif.

Die Fliegende Holländer is where Wagner discovered what it meant to be Wagner, clarifying — in his compositional practice and thinking — the concept of the leitmotif. Hardcore Wagnerians treat the work a bit like a wannabe, though. Oh, they allow Dutchman its place in the Wagner canon but grudgingly only, and then only because it can be taken as a prelude to the real guts and glory of Wagnerian-to-come: Der Ring Des Nibelungen (The Ring Cycle). (Girard directed Siegfried, the Ring’s third part, for the Canadian Opera Company in Toronto in 2005.)

The Dutchman is the earliest of all Wagner work to be — allowed to be? — performed at Bayreuth. In his many letters to Liszt, the composer — when not asking the pianist to get the German police off his trail — alluded to the weakness of German theatre in general, and its fixation on Carl Maria von Weber in particular. But Dutchman itself is saturated with Weberian High Romanticism German-style. Weber’s biggest hit, Der Freischütz helped make Dutchman possible, with Wagnerian storm-tossed seas replacing Weber’s forests rife with fat quail and Deutscher Mädel. It was fun to watch veteran Russian conductor Valery Gergiev work the horn section in the Met orchestra hard, stopping and starting to get just the right sort of Weber oomph-pa in their playing.

Girard might be described as a post-Wagnerian, unwilling to get lured into the socio/theoretical murk fogging the Wagnerian zeitgeist, yet revelling in the freedom allowed by the composer’s inherently theatrical thinking. Girard’s own background in art and pop video — he directed Peter Gabriel: Secret World Live tour in 1994 — sharpens his realization of the key moments in his narratives. (Actually, video’s on-the-fly shooting style deceives. Anything done on-the-fly is trimmed into solid, cogent narrative in the video editing suite).

Speaking of ghosts, the Dutchman is a spectral spaceman in Girard’s thinking; the oceans he travels are the cosmos. Macfarlane’s sets hints strongly at J.M.W. Turner. Macfarlane himself is an accomplished painter. For Wagner, it was supposedly a gut-wrenching sea voyage to England off the coast of Norway that provided the genesis of the idea. David Finn’s lighting design can’t swirl enough as the massive made-for-the-Met boat stealthily eases its bulk on stage. Yet in Girard’s hands, this mid-19th century nightmare is projected into the 21st century; the edged-in-gloom look might well come from contemporary French bande dessinée. “It’s in the stories and legends Wagner used,” the director tells me some days before the Met rehearsals have begun. “The Dutchman is a simple and bold story, full of a kind of youthful flamboyance. It comes from a Wagner who was flashy; it has this energy, this almost violent energy.”

“The Dutchman is a simple and bold story, full of a kind of youthful flamboyance. It comes from a Wagner who was flashy; it has this energy, this almost violent energy.”

My perspective on Wagner is this: Yes, you can treat his pieces any way you want. But I am against the kidnapping of any opera when a creative individual expressed himself through it. With Flying Dutchman, you are already exposed to deeper elements. I am here to merely have a reading of them. You do what Wagner wrote and to serve any other cause is wrong. Yes, the question of anti-Semitism is always present in Wagner’s case. But people have to put it in context. If Wagner was guilty then a lot of Europe was the same at the time, But from a dramaturgical point of view, from a staging point of view, his work remains the brightest and the purest.”

Girard’s theatrical background, not his film, was the determining factor for his Met association. “I knew of his theatre and opera work, including his part in the Canadian Opera Company’s Ring Cycle (in 2005, where Girard directed Siegfried,)” says Gelb. “The leap from film to opera is not an easy one. One of the greatest challenges is what to do with chorus, with moving 70 or 80 people on and off stage. In film, scenes can be created in the cutting room. I opera you have to create transitions live. You have to deal with that space in opera..”

Girard: “The question is why is Wagner so alive today? That’s a whole debate. Opera is the parent of film. There are parallels between film and opera of the 19th Century, But when film took over from opera, when Charlie Chaplin and all the others came along, it was the end of the operatic experience in a way. So we have had to reinvent the experience.”

But why do we keeping going to the theatre?” Girard asks rhetorically. “I’ll tell you why. It’s because when you leave it, you know you’ve just walked out of something that’s not available in any other form. Look. We all have computers and cell phones. We are completely trapped by the present and I am not excepting myself when I say that. If I were to tap “Aristotle” on my computer, it would be all there, everything about Aristotle. Never has knowledge been more accessible. But if we don’t listen to the wise old poets of the past, we limit ourselves. That’s why I was interested in Glenn Gould. He was engaged in modern technology, but he used it to reach Bach. He may have been trapped in the present, but he was interested in the future.”

Girard bristles a bit at being described just as a film director who happens to do opera — the list of his peers in this regard is long for sure — or conversely as specialist in music-based film, such as The Song of Names, last year’s below-Hollywood-radar film based on Montréal music critic Norman Lebrecht’s novel. It’s considerable sprawl over time and geography touches on an opera’s worth of interconnected themes, from growing up in bombed-out London in World War II, to the early life of a genius-level violinist, to a mystery disappearance, to a Jewish feeling of survivor’s guilt.

Yet, “it’s actually a very intimate film,” Girard insists. Indeed, at its core is a single work of Jewish liturgical chant — names of Nazi victims memorialized only through cantorial singing — composed by Howard Shore, the veteran Canadian film composer.

Maybe dreamed up is a better description. “It took me a while to do the research to write a piece that’s a true expression from my heart,” says Shore from his New York studio. “To do that, you have to have a great collaboration with someone who knows music, like François. (Martin) Scorsese is someone else who is very knowledgeable musically. The cantorial piece is a piece set in 1951, when my father was bringing me to synagogue. There were lots of discussions” — with Girard — “to bring it to life.”

“You have to understand,” says The Song of Names producer Robert Lantos. “There is no song of names. On the page, the music doesn’t exist. Yet it’s the emotional core of the work, this revelation through music. So when I read (Lebrecht’s) novel I knew that I needed a director equally at home in the languages of film and music. Is there a director who handles music better? I knew François from opera and from his (2011) work with Cirque de Soleil, so I asked him to read it. He himself could be a composer; he plays piano that well. He’s a genius, you know. I don’t think he knows it.”

The last moments of my talk with Girard turned to earlier directors’ productions of Dutchman, knowing he’s already into planning a Lohengrin, produced for the Bolshoi and the Met. I mention Joseph Keilberth’s 1955 Bayreuth version of the Dutchman, as good as any I know, not being an eclectic Wagnerian. There’s one by Van Karajan, I add.

Okay. He’ll look out for them, Girard says. “My music research is not as thorough as my theatrical research. I must listen. When I get time.”

++++

Wagner’s Der Fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman) runs Mar 2 – 27, 2020 at the Met Opera in New York City. For Met Live in HD broadcasts, see theatre listing at Cineplex Events.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- MAJOR CHORDS | Car Culture Meets The Orchestra At The Drive-In - October 7, 2020

- PROFILE | Max Richter: ‘The Pandemic Has Changed All Our Thinking’ - August 13, 2020

- INTERVIEW | François Girard Tells Us About His Unique Brand Of ‘Flying Dutchman’ For The Met Opera - February 29, 2020