The Red Violin Director François Girard returns to his roots with a musical mystery about loss and remembrance.

WARNING: The following article contains spoilers for The Song of Names, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 8, 2019.

Music and a story about loss and remembrance are inseparably entwined in The Song of Names, a Canadian film that made its world premiere as part of the Gala Presentations series at TIFF.

Based on the novel of the same name by British writer and Norman Lebrecht, the movie stars Tim Roth and Clive Owen, along with Catherine McCormack, Jonah Hauer-King, Gerran Howell, Luke Doyle, and Misha Handley, with Canadian actor Saul Rubinek in a memorable character role. [Disclosure: Norman Lebrecht writes a weekly column for Ludwig van Toronto.]

As the story begins, it is 1951, in London. The Simmonds family, including young Martin, anxiously await the arrival of violin prodigy Dovidl, a Polish Jewish immigrant, to his debut concert, financed entirely by George, the family patriarch. Gradually, it becomes clear that Dovidl isn’t going to show, and in fact, he seems to vanish without a trace. The cancelled concert leaves the Simmonds family in financial ruin; George has a stroke two months later and dies, believing Dovidl is dead.

Decades later, Martin, played as an adult by Tim Roth, is an adjudicator at various music festivals, leading a fairly dull and routine existence in a crumbling house with his wife, played by Catherine McCormack. One day, he sees a young violinist make a gesture before his performance — a gesture that was Dovidl’s trademark. It sets Martin on a journey to find the answers to the no-show that changed his life, and left him without both his father and the boy who he had come to think of as a brother.

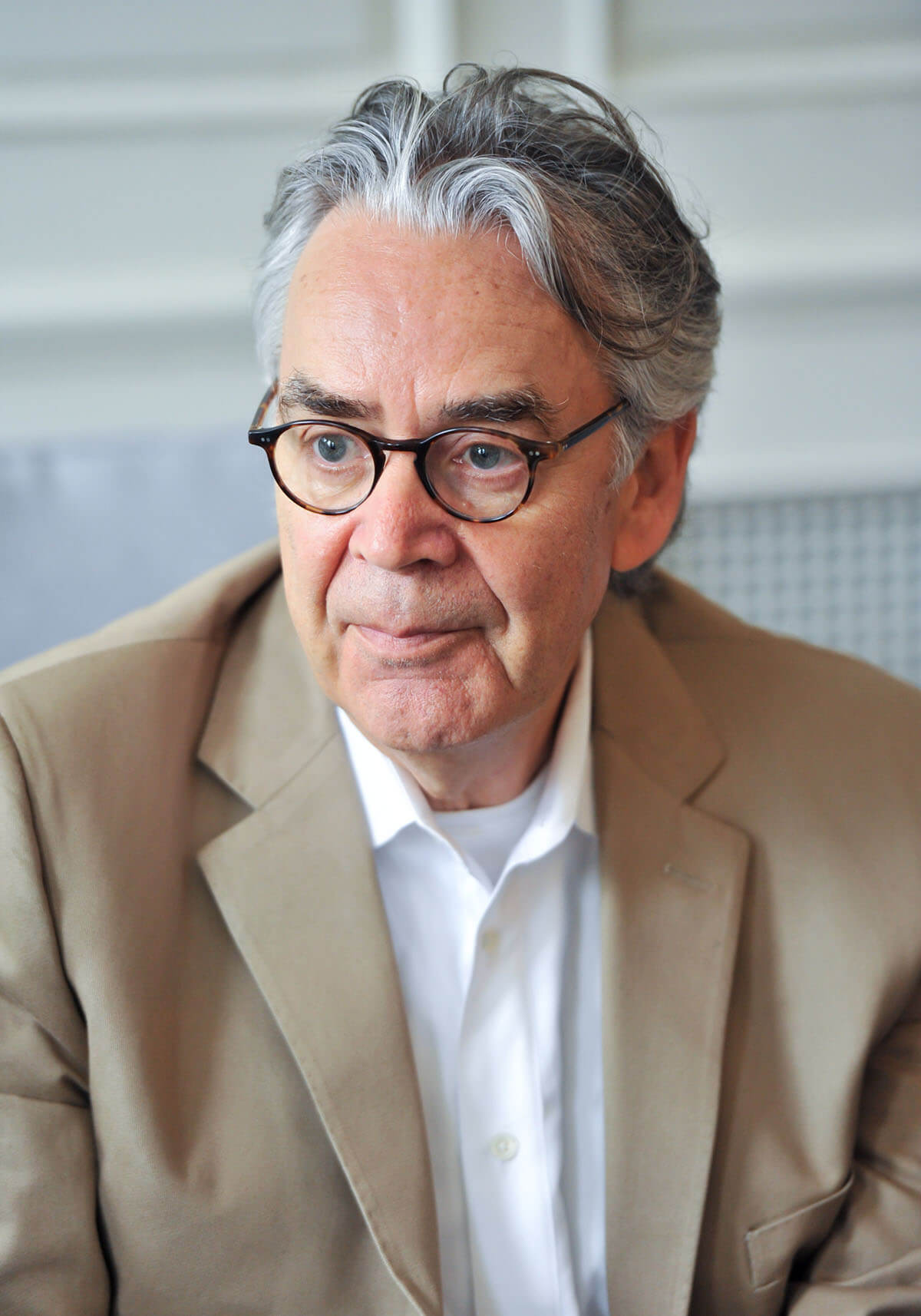

Canadian director François Girard was the natural choice to bring the story to the screen. The Quebec native’s first international hit was 1998’s The Red Violin, which also screened at TIFF, along with his Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould in 1993, among others. Along with films, Girard has directed plays and operas, including Wagner’s Parsifal at the Metropolitan Opera, and wrote as well as directed two Cirque du Soleil shows.

“I came into my door to film through music,” he says. “Opera is the mother of film.” But, when he saw that the focus of the film was a violinist, he wasn’t sure. “At first, I had a resistance to making this film,” he says — not wanting to repeat the themes of The Red Violin. But, the story, with its strong universal themes, appealed to him.

The screenplay by Jeffrey Caine is based on Lebrecht’s book, with some tinkering of the story elements for cinematic purposes. [Disclosure: Norman Lebrecht writes a weekly column for Ludwig van Toronto.] Girard read the script first, then the book, which has a completely different structure. For the movie, Caine turned the story into a mystery to add narrative momentum. “He turns it into a quest — a mystery,” Girard says. The book, however, was still the wellspring when it came to the details of character. “I often went back to the book for understanding.”

The movie is shot with rich tones, particularly in the period scenes, which are imbued with gorgeous colours and atmospheric lighting that captures the look of pre-war Europe and wartime London. In flashbacks, we learn how Dovidl Rapoport, as a young boy, was sent to live in relative (at the time) safety in London with the family of Martin, away from the looming Nazi threat in Poland. George Simmonds, a music publisher, lavishes attention — and money — on Dovidl and his talent, to Martin’s chagrin.

The story doesn’t shy from taking a hard look at its protagonists. Dovidl isn’t an entirely sympathetic character — self-absorbed, and not particularly attentive to anyone’s feelings or needs other than his own. Martin, too, is often petty and jealous of the talent and charismatic Dovidl. After the initial hostilities, however, the two form a strong bond, albeit one that is always something of a love/hate combination — like true brothers, in other words.

Casting the complex story was crucial. It plays out over three time periods, and involved using three different actors each for the roles of Dovidl and Martin, from age 10 to 13, 17 to early 20s, and then Tim Roth and Clive Owen as the two men now in their mid-fifties. British violinist Oliver Nelson helped to coach Clive Owen and Jonah Hauer-King, who play Dovidl at 55 and as a young adult, respectively, on how to make their violin playing seem realistic in the movie, and Taiwanese-Australian violinist Ray Chen plays for Owen and Hauer-King. No such effort was required with Luke Doyle, who plays the young musical prodigy. “You can’t fabricate all the musicians,” Girard says.

Doyle, a musical prodigy in his own right, plays Dovidl from age 10 to 13. The young musician comes from Glastonbury, and underwent intense training in acting, along with work a dialect coach for his Polish accent and a few lines in Yiddish. His playing in the film is real, including Henryk Wieniawski’s Variations on an Original Theme, Opus 15 and Niccolò Paganini’s Caprice #9 and #24.

As an actor, he ably embodies the role of a young Dovidl — flip and arrogant, yet also brittle, with a sadness that he carries inside the self-confident exterior. “He is also a very precocious mind,” notes Girard, who met Doyle a few times in London for casting interviews. “I realized I was the one auditioning. I knew he could pull off the arrogance.”

Girard worked with all three Dovidls and Martins in groups. The actors would discuss their portrayals, and work on the physicality and developing the strong connection and bond between the two characters. In the novel, both Dovidl and Martin’s families are Jewish, but actor Roth suggested that Martin’s family not be Jewish, creating additional tension in the story.

During adult Martin’s quest to find Dovidl, he journeys to Poland, visiting the site of the Treblinka concentration camp. It is a genuinely poignant moment in the film, which was the first feature to receive permission to shoot on the Treblinka memorial grounds.

In the story, The Song of Names is part of a Jewish tradition of remembrance, in this case, a tragic one. It is a song that the survivors of Treblinka created to memorize the names of all those who died within its gates. While the song itself is a work of fiction, the notion is rooted in Jewish liturgical traditions.

Girard gives high praise to the film’s original score by Oscar-winning Canadian composer Howard Shore, perhaps best known for his work on The Lord of the Rings. It is Shore’s haunting music that Dovidl plays as The Song of Names. “He’s been one of the most incredible companions and partners,” Girard says. There were many discussions about the movie and the story, and how the music would fit into it. Unlike most other films, Girard was looking to capture more than just mood or background music. He calls the composition “the core” of the film. “It’s not a sound he was capturing — it’s a spiritual DNA.”

Along with the film’s central themes of loss, remembrance, and how to pick up the pieces from that loss, there is another concept woven into the story.

After the cataclysmic events of 1951, and their aftermath in the decades subsequent, the film’s resolution leaves both characters with a new future. “There’s an interesting turn in Dovidl’s character,” Girard says. It revolves around the question of art and music, the individual versus the community. What is the role of art — does it serve the ego of the artist, or should it serve a higher purpose? Or, can it do both? “It questions the implications of what an artist is.”

The film has been picked by for distribution by Sony Pictures Classics. Look for a release later in 2019.

LUDWIG VAN TORONTO

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- THE SCOOP | The Glenn Gould Foundation Receives $12 Million Funding In Federal Budget - April 19, 2024

- THE SCOOP | Conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin Receives Honorary Fellowship From Royal Conservatory - April 19, 2024

- INTERVIEW | Larry Weinstein Talks About His Film Beethoven’s Nine: Ode To Humanity, Premiering At Hot Docs - April 18, 2024