NEW YORK — To call Leonard Cohen: A Crack in Everything “a contemporary art exhibition,” — as the Jewish Museum in New York does — is to suggest new ways of understanding Cohen’s very old soul have been found. Well, it doesn’t happen, maybe because this was mission impossible from the first.

This is not to diminish the work by a dozen top drawer artists. It does a good job of that on its own. Check out the cover of The New York Times, from November 11, (2016) where Donald Trump’s imminent electoral triumph is juxtaposed with news of Cohen’s Nov. 7, 2016 death. This is not just irony over-load: it’s missing the point — whatever it is — by miles.

While making your way to pieces such as The Poetry Machine (2017) by Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller — wherein a poem from Cohen’s Book of Longing is spewed forth with each organ key pressed — you ease your way through a velvety gloom into various smaller rooms found over three floors, which were once lived in by the internationally connected Warburg family back in the day. Now gloom prevails, Cohen country, the more the merciless.

I really like the Jewish Museum. It’s proof you don’t have to be big in the art business to be good. It’s been more quick-witted and sure-footed than its much bigger rivals along New York’s Museum Mile. Yet over the years, I’ve felt that, perhaps in responding to its pedigree, many of its shows were couched in a certain curatorial circumspection. This time around real, physical couches, with comfy throw pillows have added considerably to the show’s salubrious vibe. On the day of my recent visit, many museum visitors were sprawling on floors in one darkened space after another giving the entire experience the ambience of an up-scale Frat House party at Montreal’s McGill University in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Cohen’s early glory days.

Actually, this is not beside the point, it may well be the point itself. Anything about, or from Cohen is best understood from the voluptuary’s point of view, particularly when it happens in the dark. “Serious has a kind of voluptuous aspect to it,” he once wrote. (“The light” only gets in a bit, as if through a crack, sings Cohen in “Anthem,” hence the title.) Joni Mitchell famously dismissed him as a “boudoir poet.” Her intention was anything but complimentary — she also used the word “plagiarist” to describe Bob Dylan — but she was right about the sort of setting where Cohen’s work does its best work on the rest of us. The voluptuousness at the show is boudoir-like, compressed and frilly. (Note to Ms. Mitchell: As a borrower, Dylan has nothing on Bach or Picasso.)

Dylan is inevitably drawn into any discussion on Cohen although unfortunately not in A Crack In Everything. And Dylan’s voice is missed. He would have been harder and better on Cohen than any of the dewy-eyed artists. The two met over the years and discussed songwriting. (The gist of it: what took Cohen years to do cost Dylan less than an hour.) I can imagine them as Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot or, in an American context, to Tod and Buz in Route 66. Maybe they could have revived Bing Crosby and Bob Hope’s Road To pictures. Anyway, there were always parallels as the two were aware. Whatever else has resulted, Dylan’s structural analysis of Cohen’s craft is the best there is and would have given a bit of needed grit here.

On the other hand, the mansion plays an unstated role. Built-in 1906 in the French high frou-frou Renaissance manner, it was donated in 1944 to the Jewish Theological Seminary. It’s a reminder of Cohen’s own roots in Montréal’s Jewish establishment where his grandfather Lyon, co-founder of Canadian Jewish Congress, began the Freedman clothing company which was later run by his father, Nathan. Cohen’s own compass always pointed to Montréal, where he could renew his “neurotic affiliations,” as he once said and to where he was flown to be buried in the family plot.

Leonard Cohen – Une Brèche en Toute Chose, a more extended original edition at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MAC) until closing April 9 last year, occupied one vast gallery without the spatial “constraints” in ‘what is an aristocratic mansion on Fifth Ave,” says co-curator John Zeppetelli, MAC’s director and chief curator. “Even so, it was the first time they (the Jewish Museum) loosened up so much space.”

With co-curator Victor Shiffman, Zeppetelli turned the museum’s multiple spatial intimacies to their advantage, “for a concentrated environment,” he went on, “perfect for people who read complex novels but don’t go complex art installations.”

The complexity of these installations might well be questioned. Admittedly, I didn’t stay the entire time required by the projection compiled by editor Alexandre Perreault’s of 220 Cohen self-portrait drawings, while I did hang around for most of the entire well-chosen line-up of 18 musicians in Listening to Leonard (2017) for their Cohen cover versions. So, to recap: two lists of accomplishments. I did go to Ari Folman’s Depression Chamber (2017), where you’re alone in a gloomy room – what else? – while listening to Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat” as the lyrics are projected on the wall. A woman just came out as I poked my head in then to remember there was art elsewhere needing my more immediate attention. Anthony Perkins did his attic scene in Psycho better than I could.

A Crack In Everything fits nicely in the modern museology’s audience-friendly connections made with pop music, like Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock ‘N Roll at the Metropolitan Museum a block or so away. (to Oct.1) But the Jewish Museum show suggests the missed-potentials of other artistic parallels, starting with Noel Coward or maybe Gilbert (“Ne Me Quite Pas”) Bécaud. Like them, he wore his world-weariness like a formally fitted evening wear. For those who shared his life and times, Cohen, like Coward, will always remain a presence beyond his music.

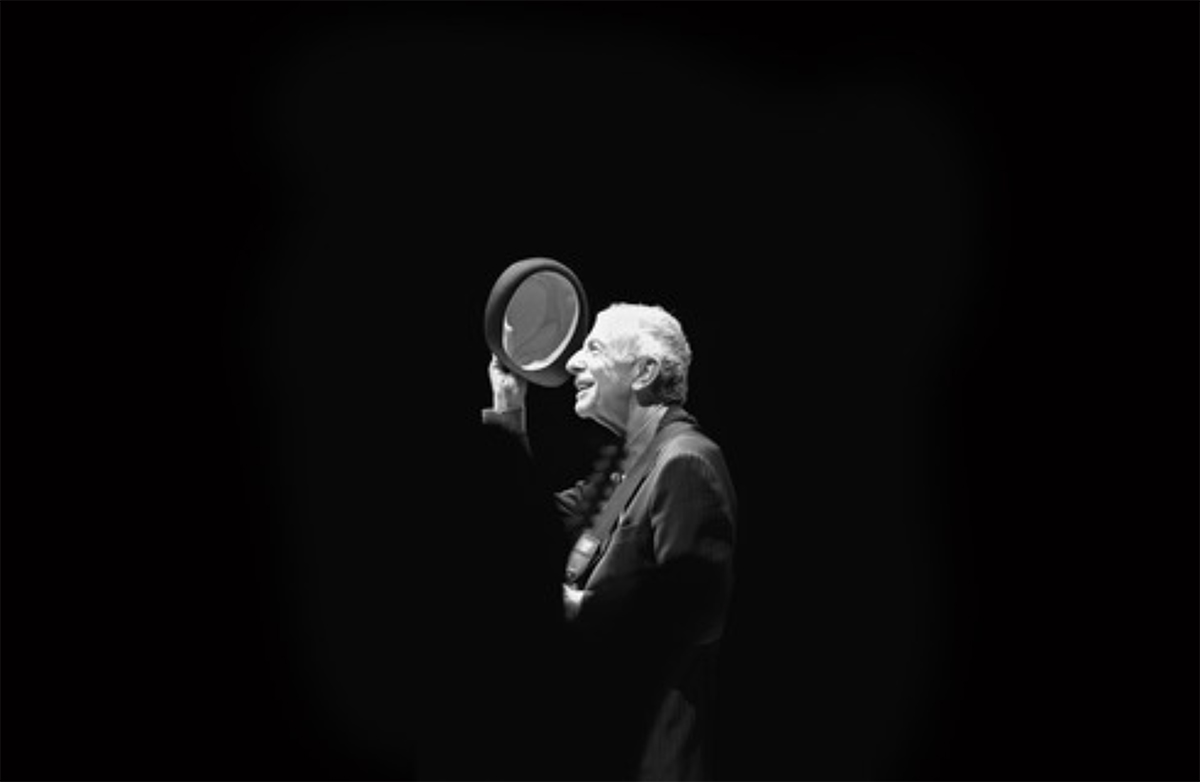

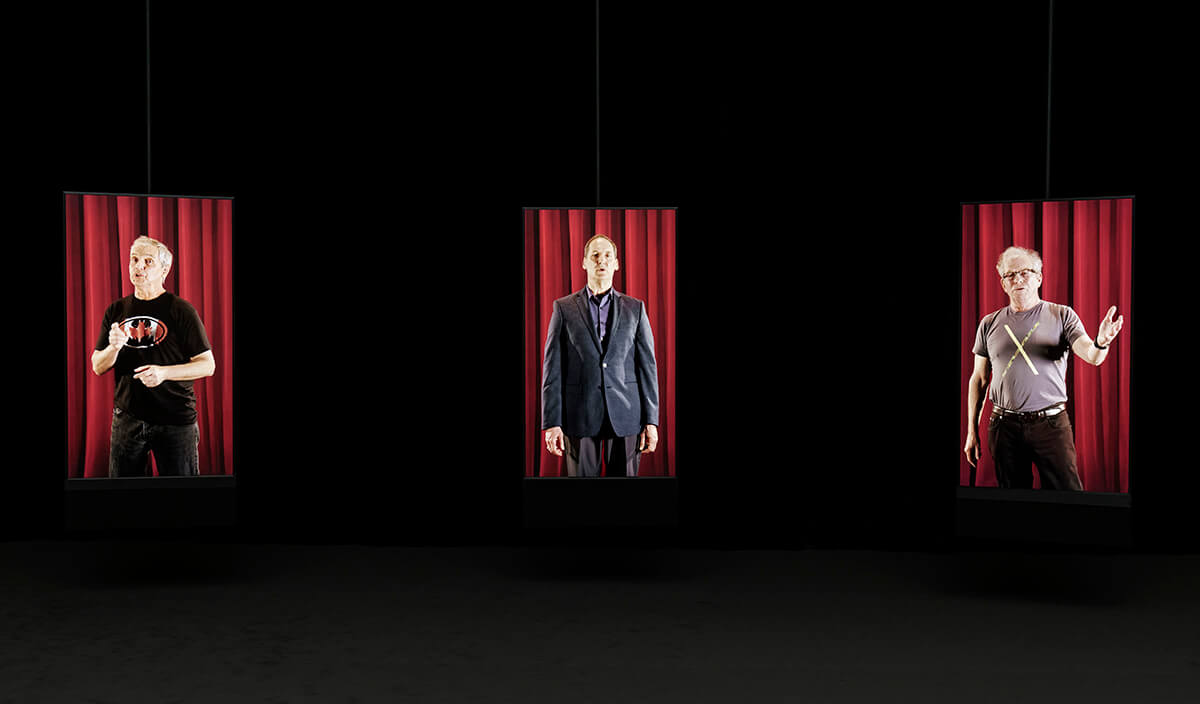

Art-wise though, the chart-topper in A Crack In Everything — visually, musically and conceptually — is South African artist Candice Breitz’s group of 18 older male Cohen fans singing, “I’m Your Man,” each version backed by members of the Shaar Hashomayim Synagogue Choir, from Cohen own Montréal congregation. Foe the visitor it works this way: The backing, a capella choir confronts you in the first of two darken rooms doing the backing vocals for the soloists you meet in the second darkened room.

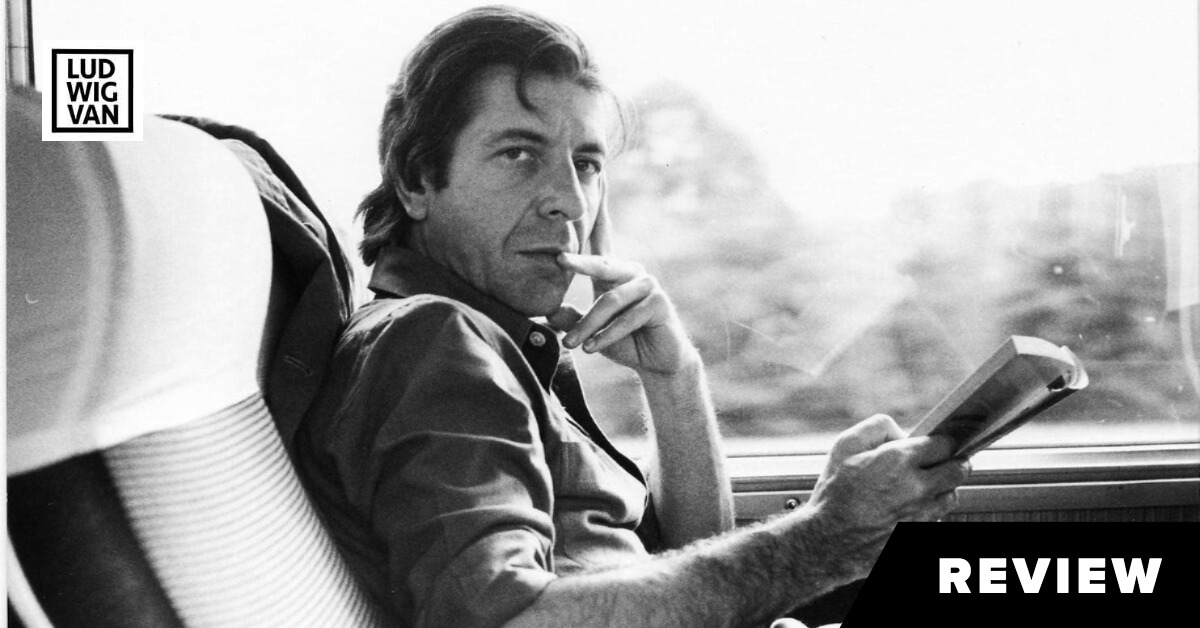

In truth, Cohen had double his share of glory days. The first — the young moody poet turned youngish moody songwriter ‘70s period — was in fact a tune-up for the second, where he emerged following the ‘90s as a world-weary aesthete with a chip on the shoulder of his famous blue raincoat.

We met a few times as this metamorphosis was upon him but, still, I best remember what didn’t change, the way his inherent playfulness would add wattage to his eyes when meeting women. It’s there in one of many video clips used in A Crack In Everything, when he tells a female TV host he’s thinking of getting a tattoo.

Where? she asked provocatively. Oh, at a little shop he knows downtown Montréal.

The evident distress of Cohen’s latter years, where he had to stay on a tour going into his 80s, although not ignored, is left for another time, for, I guess, another venue in another medium. By then his world-weariness, like his suit, was the real thing. But then, hey, he always knew where to do for a good tailor and a tattoo.

LUDWIG VAN TORONTO

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- MAJOR CHORDS | Car Culture Meets The Orchestra At The Drive-In - October 7, 2020

- PROFILE | Max Richter: ‘The Pandemic Has Changed All Our Thinking’ - August 13, 2020

- INTERVIEW | François Girard Tells Us About His Unique Brand Of ‘Flying Dutchman’ For The Met Opera - February 29, 2020