Alexander Neef figures he knows how to open a Canadian Opera Company season: Use the big bang theory. Do something major right off the top and then, if you can, go big with something else.

This year the COC director did both. And so far it seems to have worked — to a degree. Expectations for the 2018-2019 season were revved up months back for the world premiere of Hadrian, Rufus Wainwright’s second opera (after Prima Donna), the first libretto from playwright Daniel MacIvor and the promise of “a bacchanalian banquet.” What resulted was deemed to be “fairly accomplished” in the words of one critic which, to me, is praising with faint damnation and signalling a big bore.

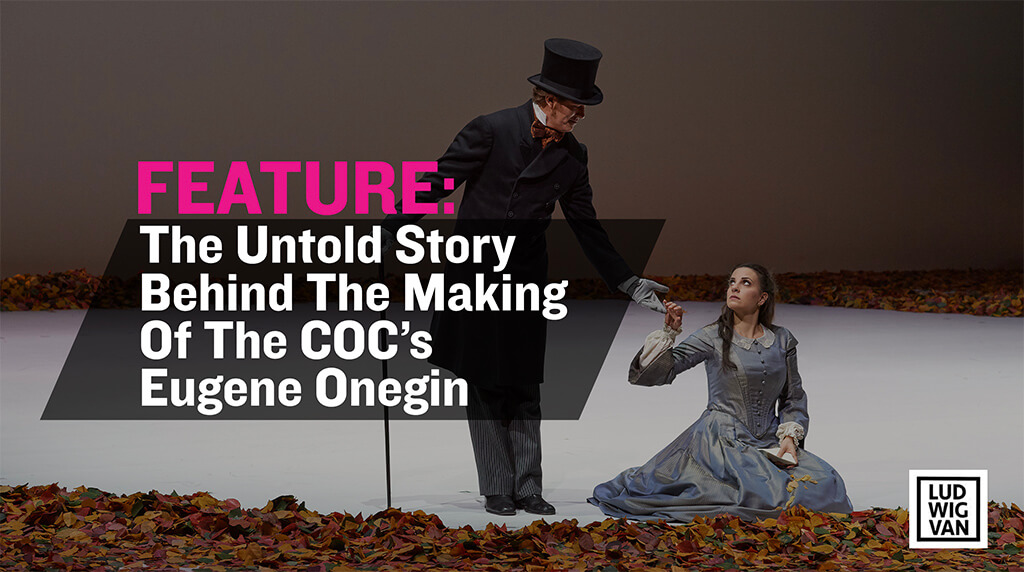

Before that though came the opening of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, which seemed to me to be a much bigger deal, in fact, one of the biggest in recent COC history. It’s nothing less than the local debut of one of the most heralded productions in recent history, one now owned by the COC and produced by the Toronto go-to duo of director Robert Carsen and designer Michael Levine.

To give this a pop cultural twist, this Onegin is opera’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. (It continues Oct. 26, 30 and Nov. 3.)

“Beautiful to see,” enthused New York Magazine critic Peter G. Davis during its second production at the New York’s Metropolitan opera in 2007. “Opera does not get more romantic than this.” Actually, opera doesn’t get any more Michael Levine than this.

“This happens a lot with Michael,” says Neef. “People walk out of one of his shows not knowing what hit them. It’s like getting opera for the first time. People are blown away that this actually exists.”

A bit of background: While emerging as a world-leading set designer, Michael Levine has been able to play God with the supernal ability to fashion unimagined new universes and to resuscitate little known old opera plots. All of this heavenly hyperbole is mine (and opera’s too, of course). It’s never Levine’s. For one thing, he believes in collaboration. For another, he sees set design as a means of “searching for solutions” lurking deep within the inner logic of a work. Divine guidance has little to do with it.

“[Michael Levine’s] sets are a living, breathing organism.” — Alexander Neef

The solutions have been jaw-dropping over the course of nearly 40 years and many hundreds of productions. They started with his career-launching sets for George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House at the Shaw Festival in 1985 where he animated a book-filled room so that its walls seemingly crept up and down. (I imagine Shaw himself would have green-lighted such wonderful scenographic legerdemain. In Caesar and Cleopatra, Shaw’s Caesar applauded book burning.)

Levine’s acutely calibrated sense of mischief surfaced early on, too. His set for Clare Boothe Luce’s The Women, a 1987 Royal Alexandra Theatre production, was filled with what appeared to be fashionable store boxes and cabinet drawers spilling over with red dresses and other “padded and soft” objects.

If Levine accomplishes little else in life, he will already have turned scenography’s role from passive to active. His sets, occasionally with multiple moving parts, establish “the geometry of the eventual play,” as formative British director Peter Brook describes the process.

“What Michael puts on stage gives a home to the piece,” Neef goes on. “His sets are a living, breathing organism.”

Dealing with stagecraft at Levine’s level of creativity is no small achievement.

Just ask Atom Egoyan.

The occasion was the COC’s 2015 production of Wagner’s Die Walküre, directed by Egoyan and supported by Levine’s abstract Wagernian-apocalyptic/futuristic look. Opera was relatively new to Egoyan but dealing with hyper-creativity was not after some 30 years on the avant-garde fringe of the movie business. Nevertheless, working alongside Michael Levine opened the film-maker’s eyes. “I was aware of the need to step up my game,” Egoyan says. “It’s amazing to be in his presence when he’s in full creative mode.”

“You have this beautiful story to tell and music that tells itself. You just have to assist it. It was a joyful moment when we realized that.” — Michael Levine

The making of Onegin is almost as operatic as the work itself. Levine’s original design was scuttled by Metropolitan Opera honchos shortly before the opening of its debut 1997 season in New York.

“I was beside myself,” Levine says, late in the evening on a phone call from Berlin to Paris a while back. “They wanted to paint some of the ideas I had sculpted. They wanted to change the design on us. It started to feel old-fashioned.”

Shocked at having to ditch so much carefully prepared preliminary work, Levine and Carsen went on a frantic 24-hour creative binge, stripping their intricately planned preliminary work of excess after excess. Many carefully researched historical touches — the original Onegin had its world premiere March 29, 1879, at Moscow’s Maly Theatre — were jettisoned. Yet the more they ditched, the more they understood what was revealed. – the “lightness of space itself,” Levine remembers.”

“You have this beautiful story to tell and music that tells itself, “he continues. “You just have to assist it. It was a joyful moment when we realized that.”

Initially, the Levine pared-to-the-bone scenography was panned by the New York Times’s critic Bernard Holland on March 15, 1997, for being the sort of opera “made to hide from its audiences.” (The singing was too light for the production, Carsen now admits, with several of the key voices due for retirement in the following months.) But word started spreading.

“One of my favourite stagings in all of opera,” one critic for Almaviva said.

This is Levine’s Greatest Hits Year beginning with the July revival at the Aix-en-Provence festival of his revolutionary 2014 production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute, directed by Simon McBurney, another frequent Levine partner.

The old architecture in Aix races dizzily from the Romanesque to the Baroque. But Levine and McBurney channelled the city’s contemporary reputation as France’s new media digital mecca. Central to their set was what can only be described as an enormous tablet crawling with singers, with the surface glowing on and off, the gizmo tilting this way and that.

Bernard Foccroulle watched audiences respond. “There’s something very generous about what they’ve done,” says the Aix festival’s out-going director, retiring to Brittany to the life of a serious composer. “The way it ends, with the performers with their arms open to the audience as if to say, ‘we are all part of the same community.’”

McBurney adds: “Michael and I fundamentally believe that music can fundamentally change consciousness. With our scenography, we ended up with something that could move and respond and change with the music. This is not a literal place or a symbolic place he creates. This is a kinetic place, a moving response to the music itself.”

Due to his oval face, his high forehead, a hairline in full retreat and earnest way of talking, Levine has drawn comparisons to Charlie Brown. It’s entirely unfair to both. Charlie is fixed forever where he is, and as who he is. Finding Michael Levine fixed anywhere, even to the highs and lows of his own history, is nearly impossible.

A Forest Hill boy from a well-off family — his father was a senior executive in the clothing trade — Levine went to high school at Thornton Hall and emerged fascinated with art history. To this day, few other designers do deeper research than he does.

“Inspiration?” he says. “We get that from doing our homework.”

Following a year at Ontario College of Art and Design (now OCAD University), Levine then went on to earn a 1980 diploma from London’s highly-regarded Central School of Art and Design. After another spell in Toronto, he set off to Glasgow and the funky Citizens Theatre.

“People walk out of one of his shows not knowing what hit them. It’s like getting opera for the first time. People are blown away that this actually exists.” — Neef

Operating in what was once one of the toughest neighbourhoods in all of Scotland, the company was energized by veteran director Philip Prowse to emphasize theatre’s visual aspects.

Back in Canada — he still maintains homes in Toronto and in London — he worked for the Shaw Festival, Tarragon and Centre Stage. And a fascinated media began to chart his ascent. In the early ’80s, he garnered nominations for Olivier and Tony awards in London and Broadway respectively for a London production of Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude.

In 1986, he was lauded as Toronto theatre’s “new step forward” in the O’Keefe Centre program, while the same year Saturday Night called him one of its “bright lights.” Yet, by 2005 Saturday Night said he “no longer qualifies as theatre’s wunderkind set designer.”

“I didn’t set out to be an opera director,” Levine tells me via Skype from Berlin during a break in rehearsals. “I started work in the theatre and still think of myself as a theatre designer, someone who designs for theatre, opera, dance…whatever. I like opera, but I also love working on plays and new creations.

“Opera tends to contract a couple of years in advance which is why I do quite a lot of them. I then have to fit theatre pieces in between as they tend to contract a few months in advance. Lotfi [Mansouri] asked me to design Idomeneo [for his COC debut], but it wasn’t until I started working with Robert that I began to do more in opera.”

“Since then, we’ve done more than 25 productions together, and more than half of them are still around and are still being revived,” Carsen says. “It’s because he’s not limited in any way,” adds the director credited with “discovering” Levine some 30 years ago for work done for the Royal Alexandra Theatre. “With Michael, I don’t think in terms of an aesthetic. We do completely different things. We don’t have a look. Michael has this signal gift in that he has a talent to explore.”

Carsen was waiting to fly from Edinburgh to Berlin as we talked. He was to meet Levine a day later to begin work on a “Hitchcockian” vision of Eric Korngold’s Mahlerian Die tote Stadt for Berlin’s Komische Oper.

Levine’s workload after Die tote Stadt continues later this year with a Sweeney Todd for Opernhaus Zurich — one of Levine’s favoured stages — directed by Andreas Homoki and starting Dec. 9, with Sir Bryn Terfel, the Welsh bass-baritone who has made the bloodthirsty role as much his as Johnny Depp made it his on film.

Theatre and opera were once local, with productions integral to the local economy, drawing on local painters, basket weavers and food suppliers. To today’s crowds, opera might just as well come from deep space. (A recent New Yorker cartoon showed a lone figure on stage saying: “Tonight’s Walküre features actual Norse Gods and takes place in the sky.”)

Today’s audiences “are more and more unfamiliar with what we do,” says Neef.

Levine — turning 57-years-old Nov.5 — meets this audience half-way, drawing on the spirit of Peter Brook, the formative British director whose 1968 treatise, The Empty Space, is to theatre what Marshal McLuhan’s 1964 Understanding Media is to electronic media.

“The set is the geometry of the eventual play,” wrote Brook, who’s still actively producing work. “A true theatre designer will think of his designs as being all the time in motion, in action, in relation to what the actor brings to a scene as it unfolds.”

Canadian soprano Adrianne Pieczonka appeared in two Levine-designed operas, the COC’s earlier production of Die Walküre (2004 and 2006) and Francis Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmelites (2013). Everything about the Wagner was earthy and grounded. But for the Poulenc, “the set was non-existent” for a look of “stark, desolate beauty,” remembers Pieczonka in a recent email. “It was truly religious to perform this opera each night.”

In 2013, the Met’s marketing-savvy new general manager, Peter Gelb, announced a Eugene Onegin production of his own, produced by Deborah Warner and to be directed by Fiona Shaw. But soon enough the splash Gelb wanted to make became a muddle of indirection.

But before that, Alexander Neef made Gelb a deal. Let the COC buy the Met’s original, 1997 production. “If, of course,” Neef said, “you are going to throw it away.” So, in a plot with endless twists, Toronto audiences will see a world-famous production, now years old, crafted by its own creative stars and owned and controlled by its very own opera house — for the very first time.

Sounds unbelievable. Over the top. Unlikely. Operatic, even.

- MAJOR CHORDS | Car Culture Meets The Orchestra At The Drive-In - October 7, 2020

- PROFILE | Max Richter: ‘The Pandemic Has Changed All Our Thinking’ - August 13, 2020

- INTERVIEW | François Girard Tells Us About His Unique Brand Of ‘Flying Dutchman’ For The Met Opera - February 29, 2020