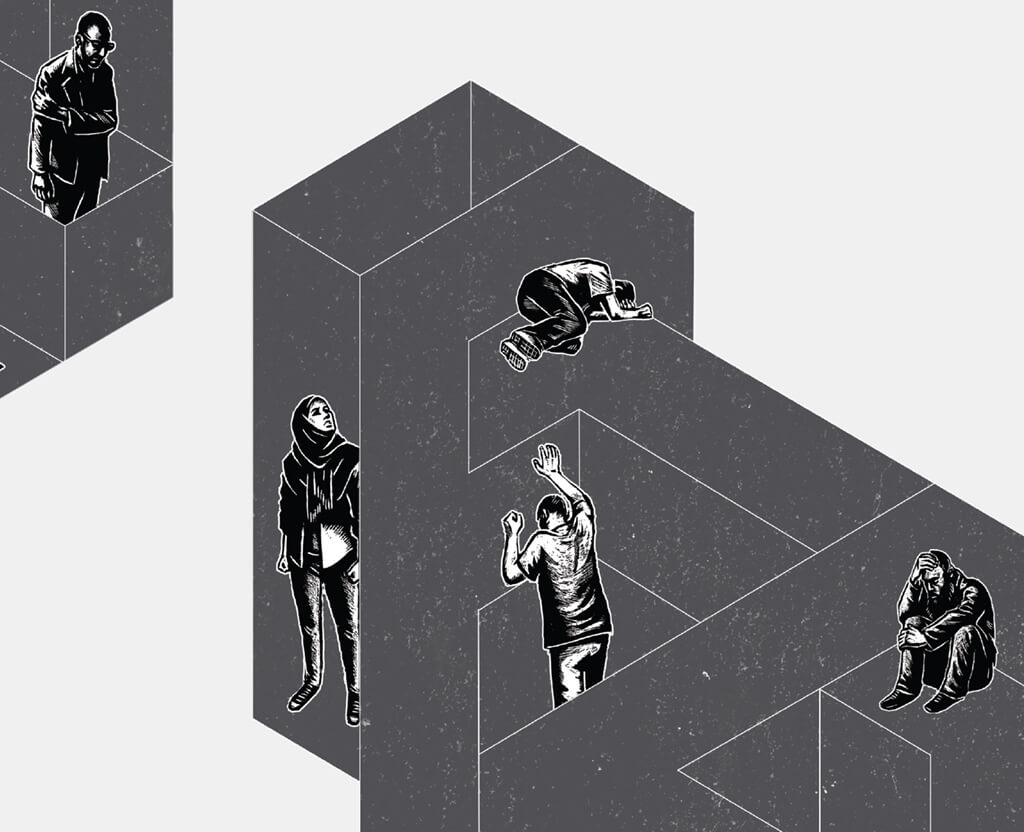

Born out of today’s difficult social climate with Europe’s refugee crisis and the divisive politics in North America, Against the Grain’s Bound explores — more importantly questions — the current state of the displaced, the dehumanized, and the mistreated. Premiering in the Canadian Opera Company’s Jackman Studio from December 14–16, these will be the first performances in a three-year “concept to realization” project. The workshop process to create the text, music, and staging began a mere three weeks before the first performance, and I had a chance to observe these provocative and revealing rehearsals.

Bringing Opera into the Present

On Monday, November 27, the performers walked into to the first rehearsal knowing little more about Bound than what can be found on Against the Grain’s website. Although AtG didn’t reveal many details about the plot or its characters because the work is not quite there yet, we do know that the performers will be Martha Burns (spoken role), Danika Lorèn (Soprano), Asitha Tennekoon (Tenor), David Trudgen (Counter-tenor), Justin Welsh (Baritone), Michael Uloth (Bass), Victoria Marshall (Mezzo-soprano), and Miriam Khalil (Soprano and AtG Founding Member).

Using arias composed by George Frideric Handel and offered by each performer, Joel Ivany (stage director and librettist) and Topher Mokrzewski (musical director and pianist) have set this music to new words, and in some changed the composition, to express a range of experiences had by contemporary refugees. Like their previous productions including a modernization of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s operas as Figaro’s Wedding, #UncleJohn, and A Little too Cozy, Ivany and Mokrzewski will push the boundaries of what opera can mean to a contemporary audience.

Inspired by the Canadian Opera Company’s Director Alexander Neef, Ivany explains that one of the reasons for choosing Handel’s music to express contemporary issues is its distance from and foreignness to today’s spectators. The music’s antiquated style offers a skeleton to explore today’s relevant issues, thereby completely changing its intent. Ivany describes Handel’s music as “pure and honest, like truth,” a metaphor for what this production hopes to find through these immigrants’ stories. Ivany went on to say that, “each person you judge has an inner beauty/truth,” but you cannot always see it at first glace. Because it subverts our expectations, Handel’s music offers a new lens to explore these stories and find new meaning.

The Possibilities of Failure

Despite this utopian view of the project, Mokrzewski expressed the fear on everyone’s mind: What if this project doesn’t work? Despite this risk, like everyone at the rehearsal, myself included, we were curious to see if it could. As a three-year production, which might be better described as a co-production with its performers, the show will certainly change with each performance depending on who is performing it and the spectators watching it. But the possibility of failure allows the team to dig into the messiness that is the current treatment of refugees and maybe find some answers.

Returning to the first day of rehearsal, questions arose about how to deal with these political topics as soon as Ivany and Mokrzewski explained the concept. For example, several of the artists raised concerns about cultural appropriation. Martha Burns, who will be performing the only spoken role in the opera, “The State,” asked such poignant questions as, “how do we make the other not ‘the other’?” and “what gives you the right to enter a culture that is not your own?” At that point in time no one had the answer, and as many of the performers noted, it would be naive to claim that any one of us could provide one. At no time was this more apparent than when Ivany raised the question on everyone’s mind: “I am white, what right do I have to articulate these stories?” However, as the group came to agree, none of us have the “right,” but we can try to engage and respect these differences by creating a dialogue.

How to Create a Dialogue with Other Cultures

The first step was to create a safe and neutral space where the performers were free to engage in a dialogue without fear of offending by asking questions that one might consider dumb or politically incorrect. Then, once they knew who their characters were, each performer was tasked to find current articles discussing the challenges these different types of people have experienced. Furthermore, they drew on their own experiences to see how different, or in rare instances how similar their lives can be to their characters’.

What I think was a stroke of genius was AtG’s strong effort to invite guest speakers to talk about the different subject matter that the performers were exploring. These included a holocaust survivor, a representative from the Canadian Arab Institute, and a member of The519-Trans-Community. These presentations addressed many of the questions asked throughout the rehearsals and offered enlightening ways to create a dialogue with people from these communities while respecting their difference. For example, the member of The519-Trans-Community captured the entire purpose of Bound in one simple sentence, “you don’t know who someone is unless you ask them.” When asked about whether women are forced to wear a veil, such as the hijab or the niqab, the representative from the Canadian Arab Institute commented that, “when people are safe, and given the choice, they will make the choice.” She went on to explain that freedom of choice in Canada provides this safe place, although the new law in Quebec policing veiling endangers this choice.

“Canada lives in a fantasyland”

Canada has a responsibility to bring forth and discuss these sorts of stories. A Canadian immigration lawyer also invited to share observed that, “Canada lives in a fantasyland.” Because our borders are three oceans and the United States, we are often freed from the ills of migrant struggle and citizens seeking asylum. This is not to deny that we have played a part: Canada has always had the capacity to take on more than its share of the struggle, from resettling Europe’s displaced masses after the Second World War, to taking in the Vietnamese Boat People, to resettling thousands of Syrians in just the past few years. However, our geography protects us from the urgency of the needs of millions of migrants, and Bound can correct the delusion that our geography can insulate us from their plight. We need to take a hard look at ourselves and assess whether we should step out to help as a matter of choice as opposed to need.

This hard look can start with a show like Bound to expose Canadians to refugee experiences that we don’t encounter with the same degree of risk as other countries around the world. Instead of reading about these stories in the news, the performers of Bound offer a glimpse at several in one show. Some might argue this show is like a peaceful protest that sheds light on opinions from various backgrounds to question stereotypes, and better appreciate the differences between these people.

When Music becomes Political

Like myself, you might be thinking how can these political and social ideas be communicated through music composed almost three hundred years ago? From what I have seen, the unexpected answer is: quite well. Although Mokrzewski warned the performers that “opera can’t be good if you pack it with a lot of information,” he does recognize that it can act as an effective vehicle for larger social and political ideas. These larger ideas are translated through what he described as the “universal humanness of opera.” Opera’s ability to embody larger-than-life emotions in a beautiful and accessible way. With this affect, opera can reach the tragedy of these stories and yet make them personable more than any newspaper.

As a musician, I am especially interested to see how Ivany and Mokrzewski use some of Handel’s original text and musical form to not only bring these ideas clarity, but also deconstruct and use the boundaries of Handel’s music to the same effect. For example, in one of soprano Danika Lorèn’s arias, they leave some of Handel’s text untouched to represent the antiquity of the character’s turmoil. The aria form typical of Handel’s style called Da Capo has two contrasting sections followed by a repetition of the first. In Bound, the repeat is either cut from the aria or used to emphasize what the character is saying.

Even the voices cast in Bound produce meaning. For example, counter-tenor David Trudgen plays a trans-woman and his soprano register translates today like someone who has transitioned from one sex to another, rather than a castrato as seen in Handel’s time. Although I have yet to hear it, some of Trudgen’s text is drawn directly from articles about a trans women’s experiences. Similarly, tenor Asitha Tennekoon sings an aria based on Un Momento di Contento from Alcina where the text includes quotes from figures such as Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Barack Obama.

One of the most interesting examples of Handel’s music being translated into a contemporary musical context is soprano Miriam Khalil’s reinterpretation of Ah! Mio Cor from Alcina. Khalil sings the first and second section with tasteful ornamentation in a traditional Baroque style, but in the Da Capo Mokrzewski and composer Kevin Lau recompose the accompaniment with tremolos to dissipate Handel’s delicate piano texture. Over an ambiguous tonal centre, Khalil sings improvised melismas to an English text. Surprisingly, this drastic musical shift did not require much alteration to Handel’s music to sound like another culture’s music. In Bound, we hear the deconstruction of Handel’s music, to show “truth,” the similarity between seemingly different cultures.

Why is it called “Bound”?

Although I missed the discussion of why the show is called Bound, if I may be so bold I would like to offer my own interpretation of this title based on what I have seen so far. Bound uses text and music to show the ways we are “bound” together. Ivany, Mokrzewski, and Lau’s treatment of the music uses the rigidity of Handel’s form to sometimes stand as an impasse to the characters saturated in ideas of a colonial past while in others the music has an affinity, a “purity” as Ivany would say, to release other interpretations, showing the likeness between one culture and another. I for one am very excited to see where this show might lead and what other “protests” it might inspire.

Readers can catch AtG’s Bound at the Canadian Opera Company’s Jackman Studio on 227 Front Street East from December 14 to 16, 2017. For more information visit againstthegraintheatre.com or email for tickets.

[Correction Dec. 11, 2017: A previous version incorrectly stated that soprano Miriam Khalil would be singing improvised melismas with Arabic text. The text will be in English.]

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and reviews before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

![]()