Against the Grain Theatre’s recent attempt at contemporizing opera, Orphée+ is described as “an electronic, baroque burlesque descent into hell.” The comparison of this adaptation with hell suggests that there is something unsanctioned or taboo about it. However, while sitting with Against the Grain Theatre’s (AtG) stage director Joel Ivany this Sunday, or rather squatting on a bench to avoid the last of the melting snow, we discussed how AtG’s mission to modernize opera might be a more authentic approach than performing operas as they were originally conceived.

Orphée+ is based on the 18th-century baroque opera Orphée et Eurydice by German composer Christoph Willibald Gluck. The ‘+’ in the title stands for AtG’s signature modernizing stamp. Ivany explains that opera is “a battle between the old and the new. This was the case long before Orphée+.”

Here is a list of reasons why AtG’s approach to Orphée et Eurydice continues a lineage of adaptation seen over the past 200 years:

1: Gluck and his 18th-century contemporaries constantly adapted their works for new audiences, and more importantly whoever would pay them to do so.

Gluck originally composed the Greek myth of Orfeo retrieving his wife from the underworld for the Viennese in 1762. This version was written in Italian and titled Orfeo ed Euridice, because in Vienna Italian opera was still considered the greatest form of opera (Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail had yet to popularize German opera). As was the case in most Italian opera at the time, Orfeo was originally performed by a castrato––basically a boy who had been castrated so that his voice would not change at puberty.

In more sensible France, the castrati tradition was not as kindly regarded as it was in Italy. As a result, when Gluck adapted Orfeo ed Euridice for the Paris Opéra, Orfeo was sung by a tenor. Gluck also had the opera translated into French and added a ballet, because the French couldn’t get enough of the ballet.

2: Famous composers after Gluck also altered Orfeo

In 1859, French composer Hector Berlioz adjusted the score again, without the dead composer’s permission. He combined the French and Italian versions and wrote Orfeo for a mezzo-soprano, the famous Pauline Viardot.

Even in the mid-20th century, with our high ideals of “authenticity” and preserving the composer’s intent, Orfeo was transposed down to be sung by a baritone like Dietrich Fischer Dieskau.

Based on these reasons, it might be argued that performing an opera “authentically” means creating an adaption that resonates with contemporary audiences. As Joel so aptly summarizes, composers over the years have “catered to the time and place to make opera work. Gluck, for example, would take a look at his musical toolbox for each new premiere.”

So, what exactly does AtG pull out of its toolbox for Orphée+?

1: Modern Instruments

AtG replaces the harp with an electric guitar and adds two synthesizers to Gluck’s orchestration. Like Gluck used popular orchestral instruments to fill his orchestra, AtG adds electronic instruments often heard in pop music. One can hear the difference between Gluck and AtG’s orchestrations by listening to these two clips, when in the opera the furies obstruct Orfeo’s decent to Hell:

2: Burlesque

Company XIV replaces the use of ballet in the French adaptation with a unique blend of circus, Baroque dance, and burlesque. In recent decades, burlesque has experienced a notable resurgence because contemporary audiences are nostalgic for the spectacle and perceived glamour of the 20th-century. Because AtG is contemporizing an old work, it is only fitting to use another genre that is itself a revival.

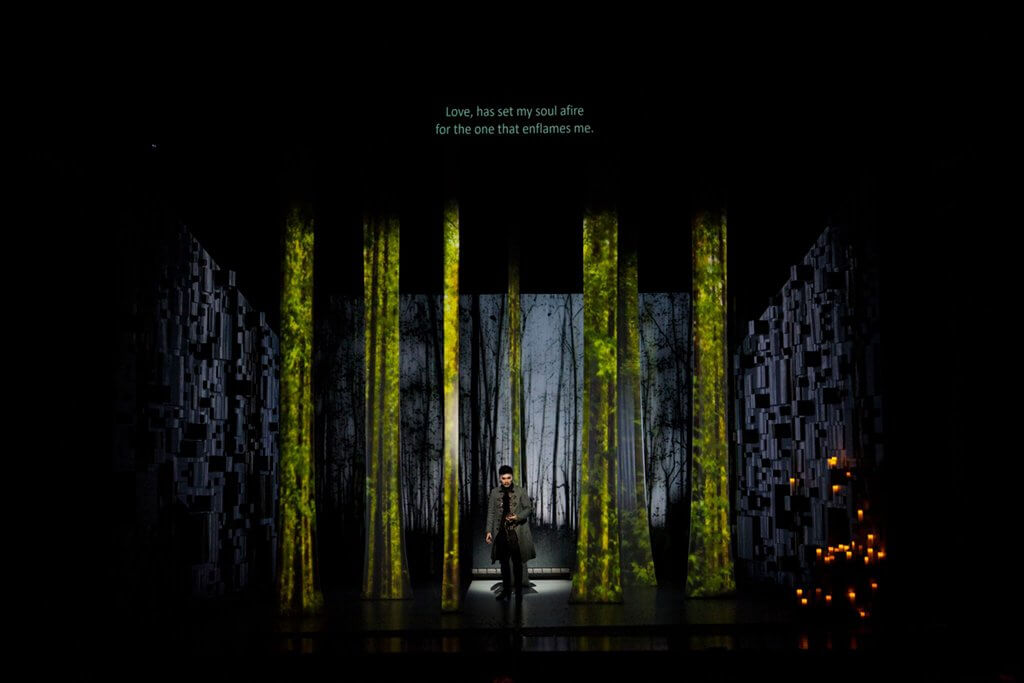

3: A Virtual Chorus

One of the most intriguing aspects of Orphée+ is the replacement of the opera’s chorus with a virtual one using a series of projections designed by S. Katy Tucker. As can be seen in the video below, anyone could film him or herself singing to join the opera. These singular voices were then edited together to create a chorus that Ivany described as being “not about precision and clarity, but the cold and distant experience created by screens.” As seen in the video, the global chorus is a colossal yet distant collective, much like the experience of scrolling through Instagram. Ivany suggests that “if Gluck had this technology, maybe he would have done this too.”

4: A 21st-Century Plot

All of these theatrical elements culminate in a 21st-century retelling of Orfeo’s struggle to rescue his wife from death’s clutches. Unlike in Gluck’s opera where Euridice miraculously comes back to life at the end, Orphée+ questions how we grieve today.

As Ivany says, with technology, we are more connected now than ever before, yet we are simultaneously more isolated. How then, does this impact the ways in which we deal with physical loss, or more commonly, virtual isolation?

Despite having done several radical departures from popular operas with AtG, Ivany notes that they “haven’t gone too far yet, we are cautiously bold and risky.” When I asked Ivany if he fears being considered conservative one day he responded, “I hope that we will be called conservative, that means that I have done my job. Also, that there is a following doing even more innovative projects.”

Before ending our interview, I asked Ivany what other ways he thinks opera might be invigorated in the future. He said, “I don’t understand why more opera companies don’t take an act from one opera and then compose different music to complete it.” Although it is an interesting concept, it is certainly not novel. Like most of AtG’s “tampering” with operas, the replacement of an act with someone else’s music was common practice in the 19th-century. For example, the last scene of Vincenzo Bellini’s I Capuleti e i Montecchi was considered ineffective to portray the deaths of the star-crossed lovers Romeo and Juliet. To rectify this, it was replaced by another composer’s last act of the same story.

Ivany aptly remarked that the “question at the end of this process is who does this work for?” I suppose we will find out soon enough if it works for Toronto as well as it did in Columbus. Orphée+ will have its Toronto premiere from April 26 to 28 at the Fleck Dance Theatre featuring Siman Chung as Orphée, Mireille Asselin as Eurydice, and Marcy Richardson as Amour. They are conducted by Topher Mokrzewski. For details, click here.