Considering the current political and social climate around sexual misconduct, Marilyn Gronsdal’s directorial note that “our actions matter” could not be more relevant. With its silent chorus of women strategically positioned on stage to comment on and expose this opera’s mistreatment of women, the University of Toronto’s production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Don Giovanni engages directly in an ongoing conversation about misogyny, sexual abuse and harassment.

Don Giovanni tells the well-known story of Don Juan, who has an insatiable sexual appetite with little regard for honesty –– let alone consent. Performed in the Faculty of Music’s MacMillan Theatre from November 23 to 26, Melanie McNeill removes the action traditionally set in 17th century Spain and instead sets the story in the timeless realm of Don Giovanni’s catalogue of “conquests.”

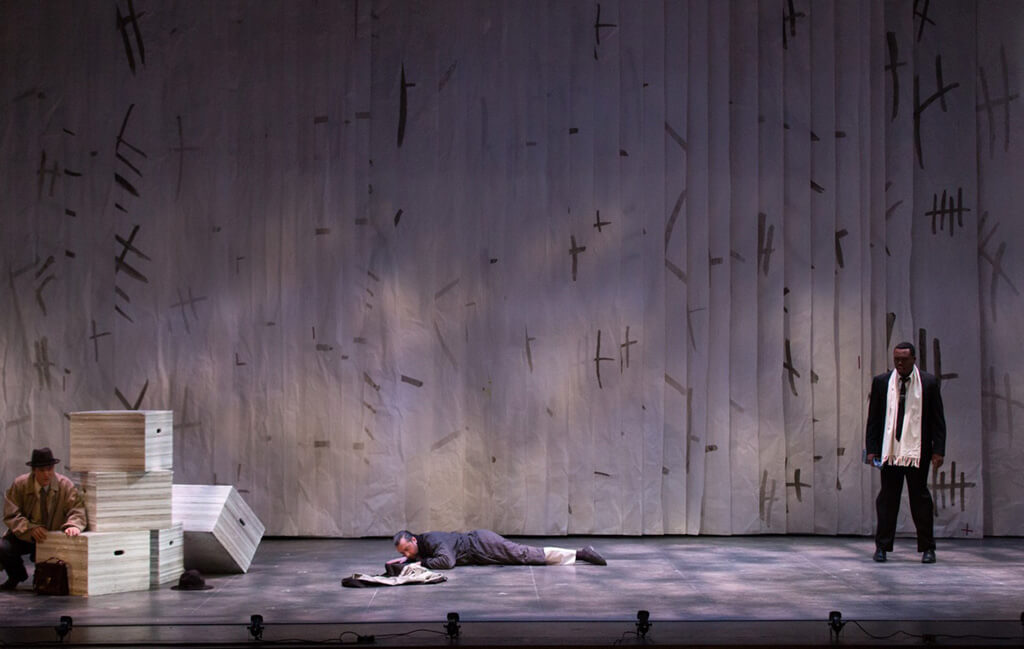

Throughout the opera, these “conquests” roam the catalogue’s pages as the silent chorus. They are dressed in somewhat anachronistic costumes that seem to trace a lineage of mistreated women through time that ends with the trio of women that make up Mozart’s main characters all in 1930’s dress: Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, and Zerlina. What they lack in sound, the chorus makes up for visually as the embodiment of feminist gaze in the opera. For example, when Zerlina begs Masetto, her betrothed, to forgive her by playfully suggesting that he “beat” her, the female chorus looks away in dismay at her display of internalized male dominance.

By updating the traditional way Don Giovanni is performed, like many professional contemporary productions currently do, Gronsdal challenges U of T’s singers to reinterpret the conventional ways that opera is performed. Despite the ingenuity of the production, the choreography, also essential to a modern production, unfortunately, did not live up to the standard set by the stage concept.

More than ever, audiences demand that performers be believable, let alone active, onstage. It is during their university careers that singers need to learn and get comfortable with looking natural while singing in any position their director calls for, so that they can compete in the industry once they graduate. Although the performance began with Donna Anna singing while at the same time struggling to free herself from Don Giovanni’s grasp (which sounds like as difficult a feat as I am sure it was), the rest of the performance barely challenged the singers. Most of the choreography consisted of sitting down to sing before standing up to “park and bark.” The only performer who showed some introspection and commitment to her limited movement was Jamie Groote as Donna Elvira.

Given U of T’s early music program, one surprising feature of the production was the decision to perform a very conservative vocal score that lacked the long-established nuances of historically performing Mozart’s music. I am referring to the repeated sections in Mozart’s arias that should be ornamented in a fashion like the Baroque traditions before him. The Canadian Opera Company and Against the Grain applied this practice to their productions of Don Giovanni, and I would hope that students who are being trained to one day perform at companies such as these, would also be informed about these practices even at this earlier stage. However, this was not apparent in this performance.

Having said this, the diction coaches’ efforts proved effective because overall the casts’ Italian pronunciation was good. However, the singers lacked the ability to navigate the natural rhythm of this language that Mozart mimics in his score’s musical nuance and phrasing. This was especially evident during sections of recitativo, the speech sung parts between arias and ensembles, where the singers were exposed by the sparse orchestration and freedom of the music.

Despite these overall observations, there were exceptional moments where particular singers overcame these difficulties. A stand out for the evening was Groote. Despite some pitch inaccuracies, she deftly performed her challenging aria “Mi tradì quell’alma ingrata” in Act II with a uniquely split voice with a bright and piercing top in contrast to a dark musky lower register. Another highlight was Georgia Burashko’s Zerlina. She sang with close attention to the musical phrasing of her Italian diction.

On the other hand, despite giving a committed performance of a seemingly demented Don Giovanni at the end of Act II, Andrew Adridge’s musical interpretation of the score lacked a basic understanding of Mozartian style and phrasing leaving his success dependant on his acting. Alyssa Durnie’s powerful and rich-voiced Donna Anna recalled the dramatic portrayals of this role popular throughout the past century. However, Durnie’s interpretation suffered due to a lack of musical nuance and laboured coloratura. Matthew Cairns, as Don Ottavio, impressively tackled one of the toughest and often cut arias in the score “Il mio Tesoro” in Act II. One wishes we could have heard more of him in Act I, if his music had not been cut. Uri Mayer conducted with an acute attention to the singers. Although some performers missed his cues, he adjusted his tempos to accommodate them and was followed by a very attentive and sensitive student orchestra.

At the end of the opera, Don Giovanni is asked to repent for his transgressions, and because he refuses to do so, he is dragged down to hell by the ghost of Donna Anna’s dead father, the Commendatore. In Gronsdal’s production, the Commendatore’s voice booms through an off-stage microphone as the women that Don Giovanni has mistreated erupt from the pages of the set. As he is killed, the women, including Elvira, each turn away as if taking back the power they had given to this monster, thereby destroying him. The women then proceed to tear apart the catalogue, finally raising their voices in defiance which is translated through the sound of paper ripping. However, what remains is that none of them raised their voices to cause this change, rather it was still though a man that they conquered their transgressor. It makes me wonder if this results from an attempt to preserve the score, or a reflection of the fact that when women expose sexual harassment, it is usually a man that executes the punishment upon their transgressor.

Even though the production ends with a triumphant display of female empowerment, I wonder if it exposes a more troubling problem about the current state of female agency. Because most judicial positions are held by men, are women still obstructed from exacting the justice they deserve?

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and reviews before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

![]()