President Donald Trump continues to inspire and normalize behavior that specifically targets and denigrates people for who they are. From mocking those with disabilities, perpetuating and normalizing misogyny, opening the doors to LGBTQ persecution, firmly institutionalizing systemic racism, and completely denigrating the free systems of journalism and press — this is not the only world leader to have done these things in the past. He won’t be the last. So what do we do? Jonathan Larson, in his iconic musical Rent, wrote a powerful line: “the opposite of war isn’t peace, it’s creation.” This series will explore choral works, small and large, created to fight against conflict, war, destruction, murder, and loss. Our doom is continuing to ignore their messages.

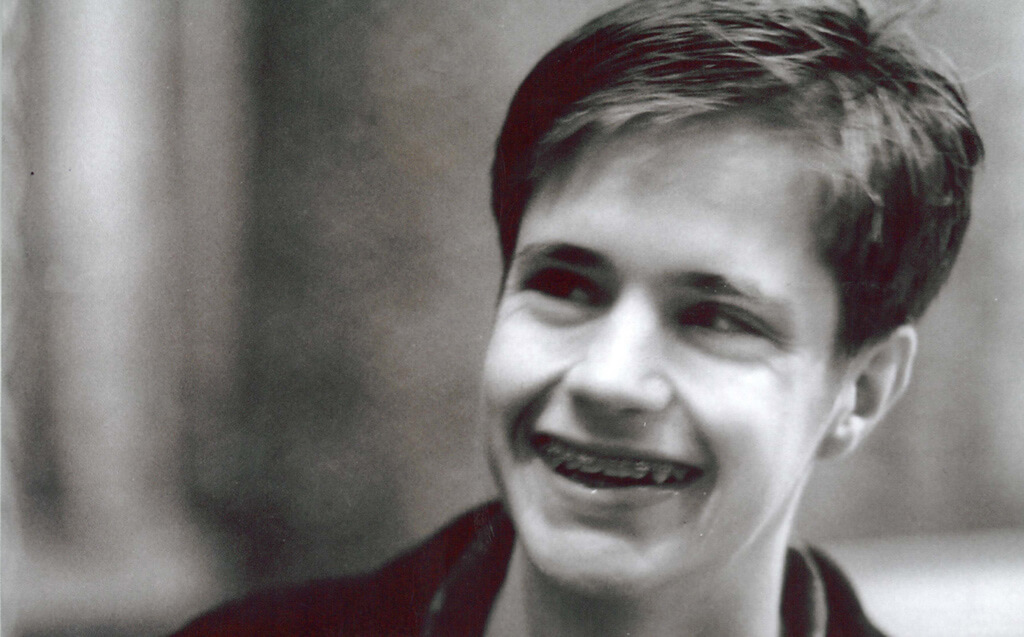

Matthew Shepard was 21 years old when he was kidnapped, attacked, tortured, and left to die tied to a fence in Laramie, Wyoming. In the years since Matt’s murder, many artistic works have been created to help explore and help remember what happened. The most famous is Tectonic Theatre Project’s play (2001) and subsequent film (2002), The Laramie Project. Filmmaker Michele Josue, Matt’s friend, documented the story in Matt Shepard is a Friend of Mine (2012). Lesléa Newman, a poet, wrote October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard (2013). Craig Hella Johnson premiered his oratorio Considering Matthew Shepard (2016) including selections from Newman’s poetry.

Johnson’s oratorio is the focus for this piece.

The text comes from a variety of sources including the Bible, many different poets, words from Johnson himself, and notably, Matt’s mom, Judy Shepard, and Matt’s own words, directly from his notebooks. Poet Lesléa Newman has a unique connection to this work and to Matthew. “One of the last things Matthew Shepard did that Tuesday night was to attend a meeting of the University of Wyoming’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Association,” Newman reflects in the program notes for the oratorio. “The group was putting final touches on plans for Gay Awareness Week, scheduled to begin the following Sunday, October 11 [1998], coinciding with a National Coming Out Day. Planned campus activities included a film showing, an open poetry reading, and a keynote speaker,” says Newman. “That speaker was me.”

There are several Newman poems from the perspective of the Fence, the Stars, and the Wind. The most haunting of which is “the Fence (that night).” A Gregorian chant opens the piece before a bare baritone solo begins, representing the fence. The solo is set to powerful text: the soft: “I held him all night long. He was heavy as a broken heart”; the accusatory: “I saw what was done to this child”; and the heartbreaking: “their truck was the last thing he saw, tears fell from his unblinking eyes. I cradled him just like a mother. I held him all night long.”

Dashon Burton was the original soloist for this portion. In a PBS documentary, he explains his thoughts on “The Fence (that night)”: “It’s incredibly moving, to think that something so mundane, as a fence, held such a significant part of this story […] You take that aspect of Matthew being held by the fence, being cradled by the fence, and it’s a very transformative experience for me as the soloist and the entire choir, to create these really haunting and moving melodies.”

There is a lot of musical play, genres, styles, and sounds throughout this oratorio. “I Am Like You” is written in an Arvo Pärt-inspired tintinnabuli chant. This particular piece stands out not just because of its musical techniques, but the words. There are glimpses of thoughts that one of the killers might have had; some reflection and thought about what they did and why they did it. “Am I like you?”[…] “Some things we love get lost along the way…”

There are country music inspired sections like “The Fence (before)”, and the opening section, “Cattle, Horses, Sky and Grass.” It provides a shape and nostalgia that helps create the space where this music is taking place, Wyoming. This fundamentally creates a tension of what sounds are appropriate to recreate a story like this.

Johnson has called this a “fusion oratorio,” including many different types of genres. Because of the host of different sounds, the piece can seem disjointed and unfocused to the listener. Paying attention to the text provides the focus, with frequent spoken recitations throughout. These spoken sets help bridge the space between disparate songs and genres. However, the overall process and journey of the music is there, providing a path through the myriad characters, stories, events, and feelings.

Near the end of the work, “Meet Me Here” is a powerful church hymn. The solo female voice is supported by a hummed C Major chord and transitions to the choir singing unison. It becomes a powerful chorus of voices in congregation, and a soprano descant uplifts the final chorus: “and we’ll dance with all the children who’ve been lost along the way.”

“All of Us” is a gospel-infused B Flat Major triumph that creates an uplifting feeling. The chorale in the middle section is warm and inviting. Transitioning up to C Major for a wide, thick final end. Johnson ends with a reiteration of the opening act, to invite us to the words of another poet, Sue Wallis: “This chant of life cannot be heard, it must be felt, there is no word…”

Johnson has managed to find a narrative that isn’t preachy, nor self-indulgent, and does not wallow in emotional weight. He’s managed to find moments in time, moments of story, moments of learning, and moments of emotion that are enough to keep us going, and ultimately, contemplative. Johnson isn’t providing us with an answer or some great overarching message about this horror, he’s merely bringing us to the table to have a discussion, and hopefully to act.

There’s one fundamental problem with Hella Johnson’s “idea” of Matt Shepard — his ordinariness. Intrinsically, Johnson has approached his work and ideas of this story with Shepard as ordinary. But there’s nothing ordinary about systemic homophobia. There’s nothing ordinary about this heinous crime. In the multitude of Matt’s own words that Johnson could have chosen, he specifically chose ones that made him seem childish and innocent. It makes the piece “Ordinary Boy” exceptionally odd to listen to. I find it hard to believe that “I love pasta; I love jogging; I love walking and feeling good, and smiling… and Jeopardy” are truly representative of what 21-year-old Matt was really about. It feels like a trivialization of Matt and his life.

There’s nothing ordinary about what Matt has become either — an icon, a saint if you will, of the LGBTQ community. His position is a reminder of what happens when we don’t continue to advocate and fight for a better future. I find it hard to attribute anything ordinary to Matt Shepard.

The attack on Matt Shepard occurred on October 6th, 1998, and it would be 18 hours before a fellow student discovered him, still alive, bloodied and almost unrecognizable. Matt Shepard was attacked because he was a gay man. Wyoming law does not recognize homosexuality as a protected class, and even now there is no anti-discrimination law or hate crime law at the state level. Federal law did not apply in this case. Shepard’s death could not be prosecuted as a hate crime.

Defense allegations of drug dealing, organized criminal activity, robbery, and sexual deviancy were peddled as excuses explaining the need to kidnap, brutalize, torture, and leave for dead a young man. The defense team attempted to use the “gay panic defense” (still part of Common Law in Canada) which would have diminished the responsibility of the attackers. After the trial, for a host of crimes including first-degree murder and kidnapping, the perpetrators in Matthew’s death were found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

It wasn’t until 2009 that hate crimes could be federally prosecuted, even if states refuse, when President Barack Obama introduced the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Act. President Donald Trump has indicated many policy positions that call into doubt protections for LGBTQ communities. Chiefly amongst these, Trump believes First Amendment rights — the right to free expression of religion — should be paramount to any protections for LGBTQ communities, or indeed other minorities. As more decisions unfurl from the White House in 2017, the danger of returning to an institutional regime where crimes like this would go unclassified, unprosecuted, and unreported may return. Trump’s very first clear target was the suspension of the executive order to allow transgender people to use the bathroom of their choice. And now, he is targeting transgender children by removing established federal protections.

Lives continue to be lost to hate crimes, bullying, and suicide. The names of victims are legion: Tyler Clementi (18), Jamey Rodemayer (14), Raymond Chase (19), Jamie Hubley (15), and Bob Nicholson (47), and of course, Matt Shepard (21). Every year, Egale Canada reports that an average of 500 youth under the age of 24 take their own lives. In 2014, 146 cases of hate crimes were investigated by Toronto police. On June 12, 2016, 49 people were killed and 53 wounded in the Pulse Nightclub shooting, a targeted hate crime. The UpStairs Lounge attack, on June 24th, 1973 in New Orleans, was the second largest massacre of LGBTQ people in the USA when 32 people died during Pride festivities. For whatever reasons, Matthew Shepard continues to be a name above all the others. So we shall consider him, and the countless lives we have lost simply because they were…

“Meet me here, won’t you meet me here, where the old fence ends and the horizon begins.” — Considering Matthew Shepard.

For more information:

The Matthew Shepard Foundation

Considering Matthew Shepard website.