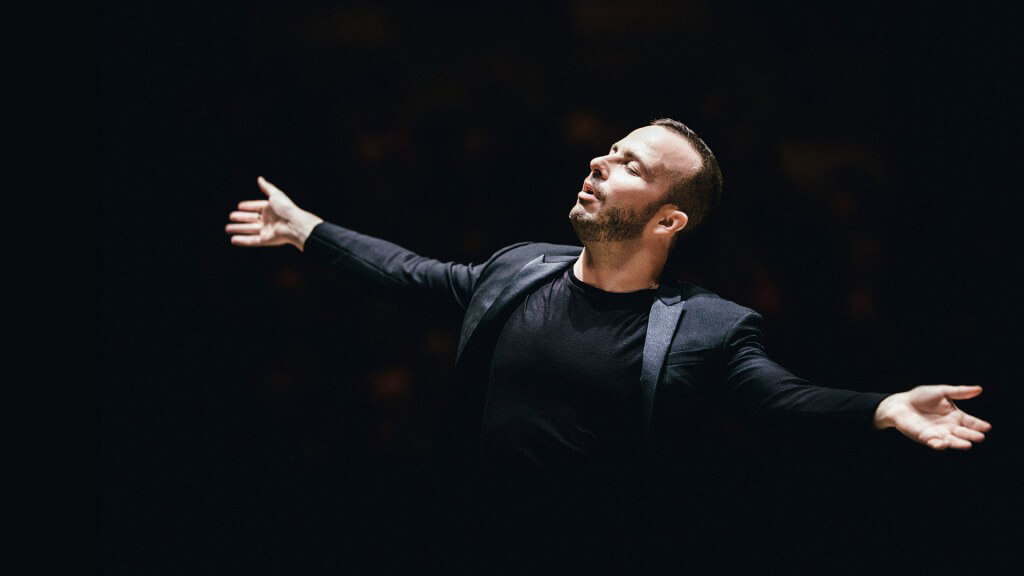

Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s career options seem to know no bounds these days. Currently music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra and soon to be music director of the Metropolitan Opera, it says something important about the character of this man that he remains loyal to the orchestra that first recognized his unique abilities and gave him the opportunity to develop his technique and his repertoire, i.e., L’Orchestre Métropolitain (OM).

L’Orchestre Métropolitain is generally thought to be Montreal’s “second” orchestra, after the Orchestre symphonique de Montréal (OSM), but when Nézet-Séguin is on the podium, this ensemble has every right to be considered on a par with the OSM, an estimation confirmed by the fact that the OM and Nézet-Séguin just made a recording with lyric tenor Rolando Villazón and bass Ildar Abrazakov for Deutsche Grammophon (DG), one of Europe’s most prestigious record labels, and the recent announcement that the OM will be making its first European tour next year.

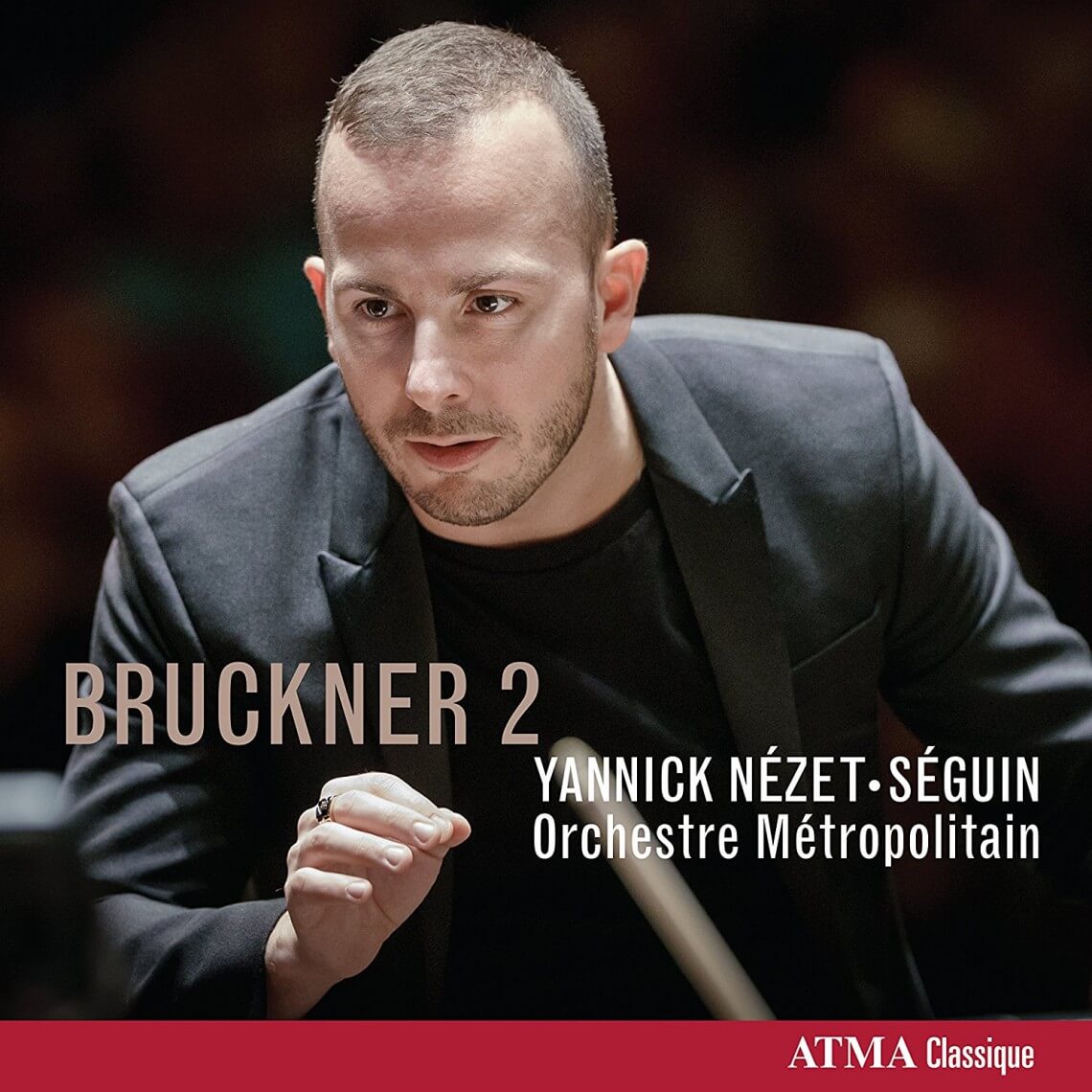

Meanwhile, Nézet-Séguin and the OM are continuing to make recordings for the Quebec label ATMA Classiques, another affirmation of Nézet-Séguin’s loyalty to both his musicians and the community that nurtured him. To date, Nézet-Séguin and his orchestra have produced 13 CDs for ATMA, including a Bruckner cycle still in progress. This release of Symphony No. 2 will leave just two more. Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 is scheduled for performance and recording in the Spring of next year, with Symphony No. 5 slated for the Fall.

Symphony No. 2 is one of the least often played Bruckner symphonies, overshadowed by the much grander symphonies 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9. And that fact presents any conductor who tackles the piece with a dilemma: should the foreshadowings of the later symphonies be emphasized or should the piece be played in a style more limited in scale and more like Schumann and Mendelssohn than Wagner? In fact, there are several recordings available using chamber orchestras, clearly emphasizing the small-scale approach: Thomas Dausgaard with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra (BIS-SACD-1829) and Mario Venzago conducting the Northern Sinfonia (CPO 777 735-2). If a Wagnerian scale is more to your taste, I would recommend either Eugen Jochum with the Bavarian Radio Symphony or Daniel Barenboim with Staatskapelle Berlin. Both conductors go for a big sound in the manner of the later Bruckner symphonies and use large orchestras. Jochum brings the trumpet parts, with some spectacular triple-tonguing, to the fore like no one else.

Nézet-Séguin, it seems to me, has opted for a reading that falls somewhere in the middle of these extremes. Although his approach is by no means small-scale, he gives us moderate rather than grandiose climaxes, and his tempos are brisk as compared to Barenboim’s, which are very slow (even when the marking is “Ziemlich schnell” or “Rather fast”) and Venzago’s, which are all over the place, and generally faster than most.

What makes this new Bruckner version so welcome is the quality of the playing. First chair players in the OM — especially principal horn Louis-Philippe Marsolais, principal flute Marie-Andrée Benny, and principal oboe Lise Beauchamp — repeatedly contribute solos that are not only beautiful but shaped with both affection and understanding. Incidentally, ATMA admirably lists the names of all members of the OM featured in this recording, but in fact offered one too many credits; there is no tuba part in this symphony.

Nézet-Séguin conducts with a clear sense of what he wants to hear and makes it happen. In no other recording have I heard the dynamics so carefully realized. He and his players must have worked especially hard to get the frequent soft trombone and horn chords not only quiet enough but together — really together.

When discussing Bruckner symphonies, it is always necessary to discuss which “version” the conductor is using and whether it is the “right” one or the “wrong” one. Bruckner made numerous versions of nearly all his symphonies – there is only one version of the Seventh, although there are still some issues — and scholars continue to try to pin down which ones are to be preferred. In the case of Symphony No. 2, although there are essentially two versions, one from 1872 and the other from 1877, that is not the end of the story. There are two widely used published versions, the first from 1938 by Robert Haas and the second from 1965 by Leopold Nowak. Fast forward to the present and the work of William Carragan, contributing editor to the Bruckner Collected Edition and one of the foremost Bruckner scholars alive. According to Carragan, the Hass edition is primarily based on the 1877 version with parts of the 1872 version mixed in. The Nowak edition is based on Haas. For the record, there is also a fairly obscure 1892 print edition which is essentially the same as the 1877 versions, with corrections, and it is rarely used by conductors.

The 1872 version (the very first version composed by Bruckner, which reverses the order of the inner movements) was not performed until 1991. This original version has been recorded by Kurt Eichhorn and the Bruckner Orchestra Linz (Camerata CD 30CM-195-6). Both the 1872 and 1877 versions were published together in an edition by Carragan (Bruckner Collected Edition) in 2005.

While Nézet-Séguin opts for the 1938 score edited by Haas (based on Buckner’s 1877 version), he does at least a little tinkering, e.g., omitting the repeats in the Scherzo for the second part of the main section and the second section of the Trio.

For some good information on the various Bruckner versions and their complexities, visit the website of the Bruckner Society, so ably tended by John F. Berky.

For more Record Keeping see, here.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

- SCRUTINY | TSO Lets Berlioz Do The Talking In Season Opener - September 21, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Even Yannick Nézet-Séguin Can’t Make Us Love Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito - September 6, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Giovanna d’Arco With Anna Netrebko Explains Why The Best Operas Survive - August 30, 2018