In a city that has a Glenn Gould School, a Glenn Gould Studio, a Glenn Gould Foundation, a Glenn Gould subway plaque, two Glenn Gould residential plaques, and a life-size statue of Glenn Gould, a speaker lecturing on this Toronto icon can expect an appreciative audience, especially when he presents him as a paragon of human creativity. Indeed, unreserved enthusiasm was the response to Professor Joshua Cohen’s presentation: Glenn Gould’s Variations and the Human Qualities that Foster Remarkable Human Creativity, delivered at the Rotman School of Management and co-sponsored by the Glenn Gould Foundation.

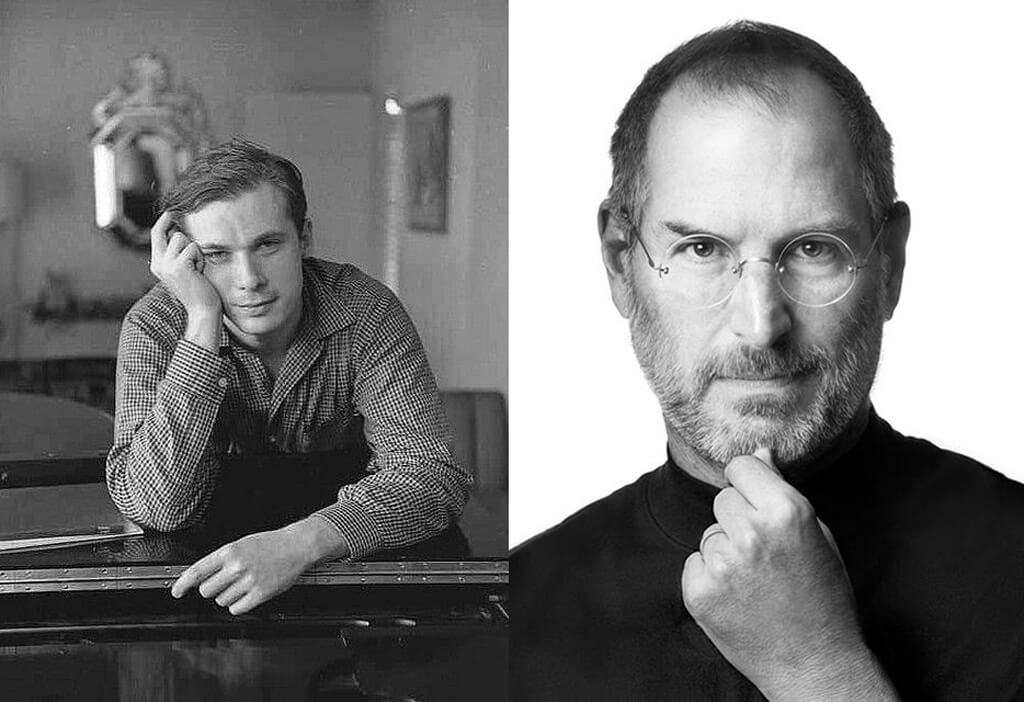

This lecture, developed for executives who attend Apple University, a corporate training facility of Apple Inc, the world’s largest technology company, is intended to support that late Steve Jobs’ goal of studying what the best things are, so that the Apple culture will aspire to such heights. “Expose yourself to the best things humans have done and bring it into what you do”, was Jobs’ advice. Cohen’s task is to identify the best things and explicate them. Gould is on his list of the best things, along with Central Park in New York City.

To facilitate an appreciation of Gould, Cohen begins by providing a grounding in Bach so that his pianistic achievements can be meaningfully perceived. It is not hard to enjoy and admire a fine performance of Bach, by Gould or other great Canadian pianists such as Angela Hewitt or David Jalbert, but to recognize the specificity, sensitivity and sophistication of Gould’s achievement requires acute perception of fine points. Cohen’s presentation was a pedagogic model of clarity and nuance that made Bach accessible to an audience of varying musical background without dumbing down by even an iota. Structuring his talk around a comparison of Gould’s 1955 and 1981 recordings of The Goldberg Variations, Cohen argued that the pianist’s desire to improve upon a recording that established a musical standard that had not then been surpassed exemplified a vision of musical excellence so high that it contained an ethical dimension. Gould’s stated goal, to create a feeling of ecstasy that can elevate and distance the listener from the mundane reality of everyday life, showed a profound concern for humans, according to Cohen.

Cohen sees Gould’s early and wholehearted embrace of technology to be part of that ethical vision. It enabled Gould’s uncompromising standards by allowing him to record multiple takes of each variation and then splice together the parts that pleased him and served his vision of the overarching architecture of the Variations. This understanding that technology could produce something more sublime than real-time performance and permit the pianist to play without the need to please an audience in a concert hall was Gould’s visionary realization and made him unique among the great pianists of the 20th–Century in Cohen’s view.

Rotman School of Management on October 18. (Photo: Robin Roger)

Cohen’s beautifully explicated, examination of Gould’s variation of tempo and dynamics in his two versions of Variation 18, which included asking the audience to identify the difference in the beat in two renderings, was a brilliant lesson in the perception of musical detail. That this proved that Gould perceived differences between versions of his playing of the smallest detectable sounds audible to the human ear powerfully demonstrated that he met Job’s ideal of accomplishing “the best things humans have done.”

Convincing as Cohen is about Gould as an innovator and musical visionary it is hard to overlook the omission of any consideration of the darker aspects of his legacy. Gould didn’t simply prefer the recording studio to the concert hall; he asserted that live performance was without value, and even repulsive, characterizing it as a vast assemblage of sweat glands. He dismissed the profound social benefits of communal musical experience, and seemed not to reflect on the evolutionary advantage that shared musical expression has given to humans. He looked at live performance from the point of view of the performer, which is understandable, but seemed to have no interest in the audience’s experience, almost as if he’d never attended a concert, but only performed in them. The world he envisioned was one of complete musical privacy in which people listen in sealed isolation, and are transported away from each other in a sublime state. That technology does allows us to experience music this way is indeed remarkable, and even transformative at times, but this does not mean that a world of people hoarding their aural pleasures inside their earphones or at home with their sound systems is an ideal. Solitude and reflective detachment is regenerating and necessary, but we deny our need to attach and share uplifting sensations at our peril.

Gould’s greatness is so indisputable that there is no need for an uncritical cult of personality. In Toronto, we run the risk of adulatory parochialism due to our pride in having produced this genius. No question, he was admired the world over by the greatest musicians of his day, not just here, but he also provoked negative reactions, such as Seymour Bernstein’s observations in the Globe and Mail in September 2014: “When I listen to Glenn Gould play Bach, I’m not aware that I’m listening to Bach at all. I’m only listening to Glenn Gould, who infuses the music with his own neurotic nature.”

This is not to say that Cohen’s points are not valid and brilliantly well taken. But when it comes to Glenn Gould, it’s fair to ask for counterpoint.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.