Most Minimalists don’t carry membership cards anymore. But they do know something about guilt by association. Just ask Russell Hartenberger.

Picture yourself in SoHo, New York, in the summer of 1970. Psychedelia was dying out. There was violence and civil unrest reported in the news. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were assassinated the year before. There was a massacre at My Lai in Vietnam. Students were protesting at eight different University campuses across the U.S.

Nineteen-seventy New York City was a hotbed for a new type of DIY style classical music that is still very much underground. The fires of political unrest set the stage for musicians to seek alternative ways to create classical music that better represented America’s cultural melting pot.

In comes Russell Hartenberger, a young graduate student from Wesleyan University, obsessed with African percussion. He was planning a summer trip to Ghana, to learn more about it. “There is something about repetition that draws you inside and puts you in touch with your inner self as a performer and also as a listener,” he recalls.

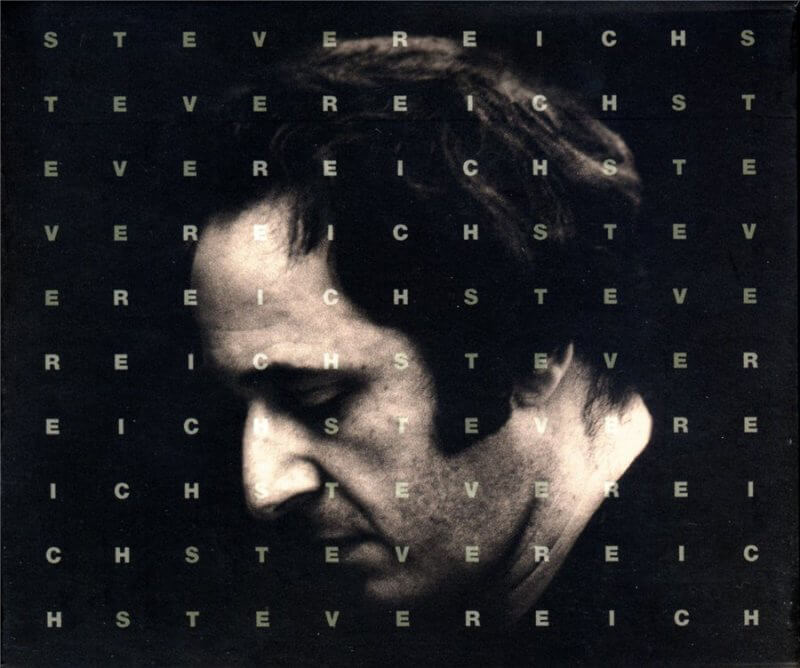

While Hartenberger was getting deep into African Drumming with his teacher, Abraham Adzenyah, he is introduced to Steve Reich, who was busy composing Drumming, a new experimental piece that uses his trademark technique of phasing. Hartenberger joined Reich’s group for a rehearsal, and “found the music really interesting and different… and I’ve been playing with them ever since — that was the Spring of 1971…”.

Hartenberger described the “rote process” as something similar to his experience learning African drumming. “Steve was composing while we were rehearsing it. He would come in and demonstrate the parts, and we would imitate it for a long time until we got it right, and then we would get to the part we learned the week before.” It was a revelation for Hartenberger. For the first time, he saw how non-western music could coexist side-by-side with Western art music.

Hartenberger secured a central place within the Steve Reich Ensemble and gained a bird’s-eye view of Reich’s compositional process. “Steve would call us between rehearsals and ask us how things went, and for suggestions. It gave us a proprietary sense of the music. It wasn’t just us interpreting what the composer wanted through notation. We felt like we were part of the compositional process from the inside.”

There wasn’t much interest in Reich’s music at the time, but more than the musicians, it was the visual artists who paid the most attention.

“We did a lot of loft and art gallery concerts,” Hartenberger says. “Most were promoted by word of mouth, but some were at fairly significant venues like the Museum of Modern Art and Borough Hall at The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). We started touring right away in 1972 to a mainly cross-over audience of young classical music lovers, and also the Rock & Roll crowd.”

Nineteen-seventy-six was the watershed year for Reich and his band of musical forthrights. Reich composed Music for 18 Musicians around the same time Phillip Glass premiered his epic Einstein on the Beach, which brought New York’s downtown music scene to a much wider audience.

The term “Minimalism” (attributable to Michael Nyman) and “New York Hypnotic School” were starting to be being used to describe Reich’s pattern-based music. Other composers, such as La Monte Young, Terry Riley and Philip Glass, all followed suit. It was an aesthetically polarizing time, where Reich served to separate those who could accept repetitive music and those who could only handle melody-based music.

“Some got it, and some didn’t,” Hartenberger says. “This was not only in listeners but performers. Some of those who didn’t were sometimes really great freelance musicians but just couldn’t get the hang of the music. It was particularly true of singers. Steve always said the singers who most understood his music were from Jazz and early music. The non-vibrato, non-coloratura style singers.” Hartenberger noted a major difference in North American performers, who are much more attuned to Jazz and popular music than Europeans. “Steve’s music has a certain kind of time feel that has connections to Jazz, what he calls ‘The Magic Time.'”

A central aesthetic of minimalist music is a focus on the whole of the sound, rather than central figures in the ensemble, such as those playing a specific melody or singing the text. Much of this comes from the musical hierarchy inherent in the music of the Steve Reich Ensemble. While Steve was always the bandleader with the final say, he had a knack for creating a friendly social atmosphere amongst the band members.

“No divas. No showboats. The music sublimated that you forego any kind of ego for the sake of the whole,” Hartenberger said.

It is this sense of repetition that is part of all music. Sound waves move through space in regular intervals of waves. The mind reproduces these sounds, gains meaning from otherwise repetitive sound waves, to make sense of the world around us. In this way, minimalism, with its focus on repetition is a return to nature.

By the early 1980s, the popular music community received word of Reich’s music, and he became a kind of cult hero figure among DJs, who proselytized the power of beat-based music. Reich became recognized as a maverick. “He didn’t have a university job,” Hartenberger said. “He wasn’t composing 12-tone music. He had his own group and was not only the composer but the bandleader.”

Over the last 10 years, Reich’s influence echoes through the top 40 radio dial. An example is Missy Elliott and Jay-Z’s “Wake Up”, [see video at 3:06] where a preacher repeatedly shouts “Wake Up,” forming the seed of a four-beat rhythm in the chorus. Whether the world knows it or not, Steve Reich’s music has changed the world.

It’s true that many card-carrying minimalists disavow the use of the term “minimalism”; The music is anything but minimal. Not only that, the “school” of minimalism was more of a circle of friends than anything. This great DIY pulsing drive has continued today with artists like John Adams, Glenn Branca, and Harold Budd, as well as the “mystical Minimalism” of Eastern Europe with Arvo Pärt as an unexpected spiritual offshoot.

Fast-forward to 2016, and things come full circle to Toronto next week when Hartenberger — now a professor of music at the University of Toronto — joins Reich at Massey Hall to celebrate Reich’s 80th birthday. They will perform Clapping Music, which is something they haven’t done together since 1973. The one-time event will also include two of his masterpieces, Tehillim, and Music For 18 Musicians.

Hartenberger promised the rare concert will be an “intensive” homecoming — and a chance to hear two giants of music come together, once again. But whatever you do, don’t call it minimalist. This will be big, grand, music.

Steve Reich @80 takes places at Massey Hall, on Thursday, April 14 at 8.p.m. More details found here.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Get our exclusive newsletter here and follow us on Facebook for all the latest.

- THE SCOOP | Royal Conservatory’s Dr. Peter Simon Awarded The Order Of Ontario - January 2, 2024

- THE SCOOP | Order of Canada Appointees Announced, Including Big Names From The Arts - December 29, 2023

- Ludwig Van Is Being Acquired By ZoomerMedia - June 12, 2023