When creating feels like pulling teeth, it’s time to look at other ways to work smarter, not harder.

If you are going to write music you have to start somewhere. For me, it means sitting in front of a piano until something miraculous happens. The process is brutal. I question everything, including myself. After a period of hysterical neurosis, I write, then re-write phrases over-and-over again with equal parts poeticism and pragmatism. It goes on like this until the musical form starts to reveal itself and I begin to understand what the piece is trying to say.

I’ve gone through this enough times to recognize my pattern. At the end of each composing day, I’m left with a self-congratulatory feeling of “This is awesome!” By the next morning, I look at what I wrote the previous day and usually hate it. It’s tough on the ego. “How could I have deceived myself into thinking this was any good yesterday?” This carries on until I find the music somewhat tolerable. God hath no fury like a composer struggling to write music – just ask my family, god bless ’em.

I’ve been thinking about the process of writing music and wonder if it’s for me to create something without it feeling like pulling teeth?

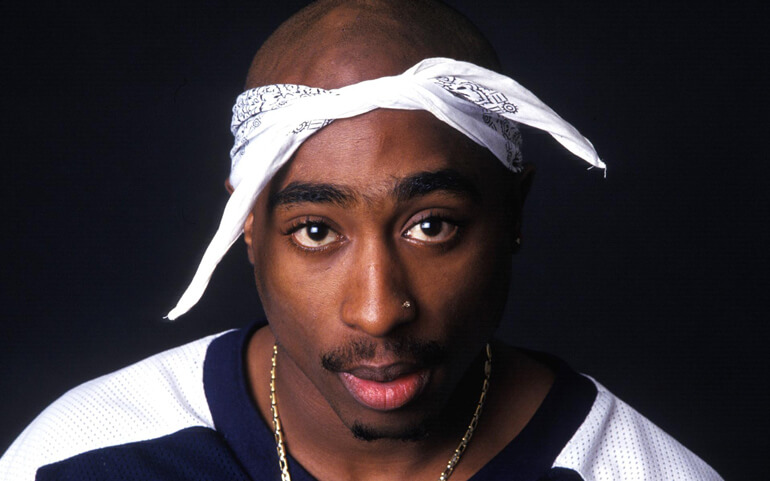

After some research, I found a book by Jake Brown, which outlines the working process of hip-hop rapper, Tupac Shakur. It turns out Tupac had a really smart way of composing in the studio, which resulted in an incredible amount of material produced in a short period of time. Shakur never experienced burnout, and his work ethic resulted in a reputation as one of the most prolific artists in the business. Shakur died in 1996, and even after being dead for twenty years, troves of his unreleased tracks are still being posthumously released.

So how did he do it?

The Dotted-Line Principle

According to Brown’s book, Tupac’s secret was the “Dotted-Line Principle” – a process that follows the flow of creativity with delayed revision.

“He came in there and said it how he felt it, and he’d be gasping for air… missing words here and there. …It was like the dotted-line principle. When he would gasp for air and miss a line, he’d put it on the next track, and maybe he caught that word. So he would triple his vocals to make sure every word was said.”

The routine had Tupac working on songs in the studio for just a few hours at a time; they were recorded as quickly as possible. When he got stumped, he ignored them mistakes without missing a beat. He had plenty of mental gaps, but his imagination was free to leap between the fast flowing ideas completely uninhibited.

Tupac would go back to the studio the following day to fill in the gaps from the day before. His inspiration guided the process like a child at play and created a level of freedom that allowed for spontaneous creations and at the same time – a work ethic that polished those creations into well-crafted songs.

Applied to composing classical music, Tupac’s process can be a powerful tool. It probably won’t work for everyone, but somewhere inside a seemingly endless flow of music just might be your next Concerto.

The TK Trick

As a writer as well as a composer, I’ve found the Dotted-Line Principle has a parallel. There is a tradition in journalism of using “TK” as a placeholder for something that needs looking up later on. By allowing for a temporary glossing-over of the small, yet important details, the writer can better focus on the big picture as much as possible. The form of a piece can be crafted more quickly, leaving the details and mental gaps to be filled in later.

Here’s an example:

TK *Catchy Title*

Born in Buffalo. N.Y, John Doe moved to Saskatchewan in 1965, then later settled in Toronto, ON. TK VERIFY.

Doe formed the Toronto String Quartet with students from the University of Toronto in TK DATE. The group quickly found critical aclaim touring in TK CITIES.

The “TK” trick runs on the same precept as Tupac’s Dotted-Line Principle. There is no getting stuck. No having to stop the flow of writing to look something up. It allows you to compartmentalize that task and focus much more on each of them.

Whether it is the Dotted-Line Principle or the TK trick, when applied to music, they can double, or even triple the amount of music you write in one sitting. This vast amount of content will be there to draw from when you start to edit. You will need to be as ruthless about what makes the final cut.

It’s important to stress that this is not a recipe to write music without rigour. The hard work always needs to get done, but this approach can work very well.

Combinatorial Play

One of the best parts of this technique is the sense of uninhibited creativity similar to how a child plays. It allows creativity through the combination of blocks of knowledge, strands of memories, bits of information, sparks of inspiration, and other existing ideas. Einstein once referred to the secret of his genius as a kind of combinatorial play.

Author and journalist Arthur Koestler explained creativity as the combination of elements that don’t ordinarily belong together. We can see it most clearly in poetry which cooks various fragmentary thoughts into beautiful ideas.

The Harvard Business Review said it best: “If associations are made between concepts that are rarely combined—that is, if balls that don’t normally come near one another collide — the ultimate novelty of the solution will be greater.”

Psychologists have studied this idea extensively and found that it works because the mind likes to create free associations, which are then sorted into those that are useful in some way.

This free association can also create a type of creative block, or option paralysis, where too many options make choosing between them difficult.

This is where the pressure of a deadline becomes useful, as choices made under pressure seem to be made more easily. They call it “The Time-Pressure/Creativity Matrix” which happens when someone comprehends that solving a problem or completing a job is crucial. This is why psychologists have found that procrastination can be a healthy thing.

My motto has always been, “If I don’t do it, then no one will do it, and if no one will do it, it won’t get done, so I have to do it.” It’s got me through many a long night.

Recap:

1: Work like a child plays

2: There is no connection between perceived effort and creative value

3: Creative flow contributes to the feeling of continuity in music

4: The more music you write during the draft phase, the more selective you need to be with what makes the cut.

5: Don’t skirt the details, but don’t let the details skirt the flow either

6: Come back to the gaps later (TK)

7: Free association is where the ideas come from

8: Deadlines are your friends

#LUDWIGVAN

Follow Musical Toronto on Facebook for the latest classical and opera news, pretty pics, funny stuff, and an insider POV.

- THE SCOOP | Royal Conservatory’s Dr. Peter Simon Awarded The Order Of Ontario - January 2, 2024

- THE SCOOP | Order of Canada Appointees Announced, Including Big Names From The Arts - December 29, 2023

- Ludwig Van Is Being Acquired By ZoomerMedia - June 12, 2023