The Italian soprano, Magda Olivero, one of the great verismo singers of her day, died in Milan, on September 8, 2014, a few months shy of her 104th birthday. With a career which lasted over five decades, (she never officially retired), Olivero’s popularity grew to cult status. Her fans – which the New York Times coined, Magdamaniacs – whipped themselves into a frenzy with each appearance of their idol. It was an amazing turnabout for someone whose first radio audition resulted in the assessment: “[Olivero] possesses neither voice, musicality nor personality… She should look for another profession.”

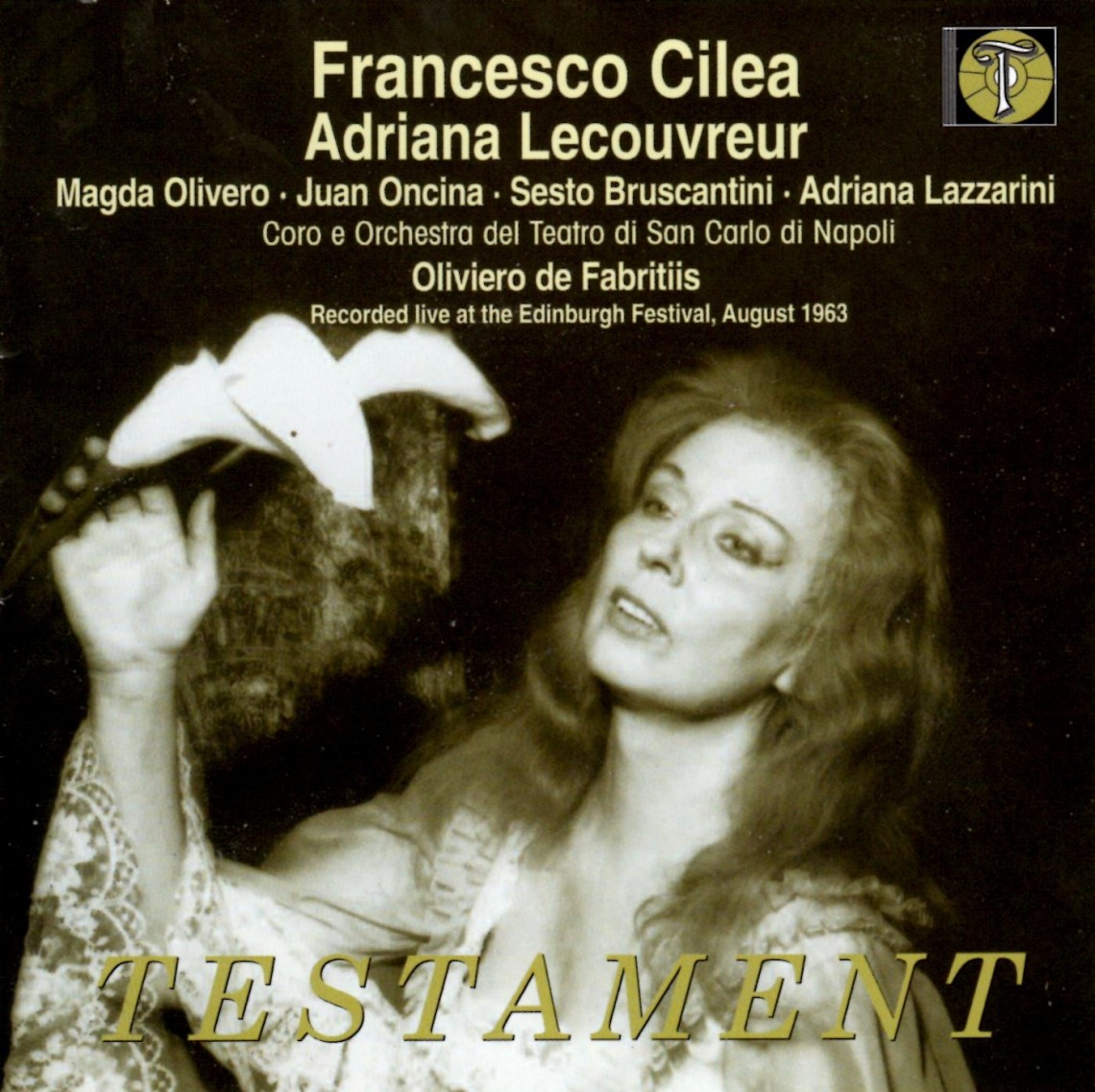

To pay tribute to this unique artist, Testament has released a live recording of Francesco Cilea’s opera, Adriana Lecouvreur, one of Olivero’s signature roles. The production, by the Teatro di San Carlo di Napoli, was recorded at the 1963 Edinburgh International Festival in Scotland, and was conducted by Oliviero de Fabritiis.

The libretto for Cilea’s opera was based on the life of a real personage – Adrienne Lecouvreur – who was one of the most famous tragediennes in early 18th century France. Apart from her talents as a thespian, Lecouvreur was also known for her clandestine affair with Maurice de Saxe and for her suspicious death. Although not confirmed, it is thought that Lecouvreur was poisoned by her rival, the Duchess of Bouillon. Apart from Cilea’s opera, Lecouvreur has been the source of several films, including one starring Joan Crawford.

Born in 1910, Olivero made her professional operatic debut in Turin in 1933, at the age of 23. Within a few years, she had established herself as one of Italy’s hottest new talents, securing her reputation over the next few years by singing everything from Lauretta (her debut role), to heavier roles such as Cio-Cio San, Mimi, Manon Lescaut, and even Elsa. In the 1939/40 season, she also added Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur to her repertoire – a role which was to play an important part in her career.

After only eight years of professional singing, and while her popularity continued to grow, in 1941 Olivero decided to get married and retire from the stage. During her ten-year ‘retirement’, she continued to sing the occasional concert for charity and, as she put it, “…just for myself, as a daily relaxation.”

In 1950, Francesco Cilea (who was in failing health at the time) wrote to Olivero asking her to star in an upcoming production of Adriana. “An artist owes something to her public and to her art, and cannot neglect these duties, because to try to avoid them amounts to desertion.”

Torn, but still undecided, Olivero then received a phone call from a colleague who told her that Cilea did not have long to live, and that he had said, “Please, plead with her. Tell her that at least once, once more, she must sing Adriana on the stage.”

“How could I refuse?” Olivero replied.

So after an absence of ten years, Olivero made her return to the operatic stage, as Adriana, on February 6, 1951 at the Teatro Grande, Brescia. “I recall,” says Olivero, “without false modesty, it was a triumph.” Olivero dedicated her performances to the memory of Cilea, who had died two months earlier. “At the end of opening night, the whole audience stood up…” she described. “It was for me, an unforgettable evening. After that night it would have been impossible for me ever to forsake the stage again.”

VERISMO: ‘Verismo’ is Italian for ‘realism in the arts’ – especially in 19th century Italian opera – drawing its themes from real life and emphasizing naturalistic elements.

Although Olivero sang a wealth of repertoire throughout her career, it was the verismo operas by composers Alfano, Boito, Giordano, Leoncavallo, Mascagni, Puccini, and Zandonai that formed the meat of her repertoire. A character that was simply a vehicle for good singing was not enough. She wanted to be totally immersed in a role. “A character that I could act, that I could live – that’s what I sought,” Olivero said.

Fans who saw her perform live speak repeatedly of Olivero’s stage presence and her acting abilities. “One has to find the right facial expression for what one is saying and singing,” she says.

You have to experience the character from inside and not from outside (which is superficial). Every word, every note, has to rise from inside and go forward to the audience. The audience then feels the emotion. If one just sings, without putting in any heart or soul, it remains just beautiful singing, and not a soul that sings.

Although Olivero had an exceptional vocal technique with enviable breath control, even she admitted that her voice wasn’t particularly beautiful. Perhaps this was why she was ignored by record labels. In 1938 she recorded a complete Turandot (Liù) opposite Gina Cigna; while in 1969 Decca made a couple of studio recordings, including Giordano’s Fedora and highlights from Zandonai’s Francesca di Rimini – both with Mario Del Monaco. Along with soprano Leyla Gencer, however, Olivero was a ‘Queen of the Pirate Record’ as countless of her live performance found their way into private collections – only enhancing her cult status.

From 1951 until her final stage production (Poulenc’s Le voix humaine in 1981), Olivero sang in opera houses around the world. Her appearances in North America, however, were surpassingly few. It was with the instigation of the great American mezzo, Marilyn Horne, that Olivero (then 65) made a belated debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1975 singing three performances of Puccini’s Tosca in the house, and seven more with the Met on Tour.

Harold Schonberg, music critic for the New York Times, wrote “…[her fans] yelled and screamed when she came on. They broke into arias with bravos. They moaned orgiastically. At the end there was a 20-minute ovation for the lady. It was one of the longest ovations in recent Metropolitan history. One would have thought that a combination of Tebaldi and Callas was making her debut.”

But when all was said and done, even Schonberg had to acknowledge that with Olivero’s performance, history came to life. “One could see what a grand style of acting it must have been,” he concluded, “as the soprano, despite her age, gave us a feminine, fiery, utterly convincing Tosca.”

One of Olivero’s colleague in the pre-WW II era, soprano Gilda dalla Rizza, said of her in an interview in 1975. “She is the only one I would walk a long distance in the cold and rain to hear today. We will not speak of the voice – it is what it is – but this woman knows what art is all about. I was so moved by her Adriana that I thought, God has helped Magda keep going so people can still know what it was like when singing was art.”

MET: 1975 – TOSCA:

- THE VOICE | Renée Fleming Turns Gold at Roy Thomson Hall - November 7, 2015

- THE SCOOP | Glenn Gould: Celebrating Genius with Cupcakes - September 28, 2015

- SCRUTINY | The Rebirth of R. Murray Schafer’s Apocalypsis - June 30, 2015