With the National Arts Centre Orchestra

On February 9, Truth in Our Time, with the National Arts Centre Orchestra under conductor Alexander Shelley, and with violinist James Ehnes, will be released by Orange Mountain Music. The recording showcases the premiere of Philip Glass’ Symphony No. 13.

In addition to the signature Glass commission, the live recording includes Korngold’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 with soloist James Ehnes, along with Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 9 in E-flat Major, Op. 70, Nicole Lizée’s Zeiss After Dark, and Ottawa-based slam poet and singer-songwriter Yao’s piece “Strange Absurdity / Étrange absurdité”.

The work and full program featured on this new release were premiered in Toronto on March 30, 2022, and then traveled to New York City for its United States premiere at Carnegie Hall on April 5 to much acclaim. In particular, the American press singled out Alexander Shelley and the NAC Orchestra’s nimble transitions between musical genres and eras. A live recording was captured in the National Arts Centre’s Southam Hall.

“I think stylistic agility is a must for any modern orchestra,” notes NACO Music Director Alexander Shelley. While he relishes that flexibility, there is also a need for balance. “I think that it then begs the question, how does that marry up with the idea that an orchestra has its own sound?”

As far as his own practice, he approaches the orchestra’s regular repertoire, which, like that of the new album, veers from the traditional to new music, with an even regard. The classical music world is, as he notes, at something of a crossroads between adherence to traditional styles and the demands for relevance in the modern world.

“The way I try to frame it, there has been a moment in classical music, let’s say the last 90 to 100 years, in which, for the first time in the history of classical music, whatever that term means, we’ve moved to an industry where we don’t look at what’s being written now.”

The world of Western art music moved in a forward direction until about Schoenberg and his 12-tone toppling of centuries of harmonic theory. After that…

“Where’s the new music?” Shelley wonders. “In the middle of the 20th century, it became more commonplace to experience the living museum in the concert hall.”

In fact, that itself is a fairly recent trend. “We think that performing new music is a new trend,” he notes. “There’s a lot of conversation to be had in that.”

Any art form has to incorporate the new and the old to remain healthy and vibrant in the society in which it exists. Studying older works only underscores the reality that they spoke directly to their own time.

“A connection with music that speaks to our time […] whose sound reflects something of this great tapestry we call life, is not only an interesting exploration, but also a reminder that music of then was also connected to its time.”

It’s why centuries old works still speak to modern ears. “Things that truly reflect the human experience of their time endure,” Shelley says. “The human experience hasn’t really changed in a couple of hundred years.”

Philip Glass Symphony No. 13

“The whole program was conceived around Truth in Our Time — as a national organization, it’s interesting to ask ourselves what role music and art […] can play in society.”

The recording came about as the NAC Orchestra contemplated its place in the world. As a national organization, what big themes should be addressed? There are so many — climate change, identity politics, the pandemic, and so much more.

But, behind all these themes, and in our society at large, a larger question looms, one about the nature and our perception of truth. What is objective truth — does it really exist? When we can hear what passes for the truth from so many sources, how do we know what is true and what is not?

As a national organization, Shelley knows NACO has the clout to take bigger risks than most, and to aim for a true expression of the times.

“A lot of the questions of today revolve around truth and the concept of it,” he says. “Exploring the question of truth seemed like a very interesting thing to do.”

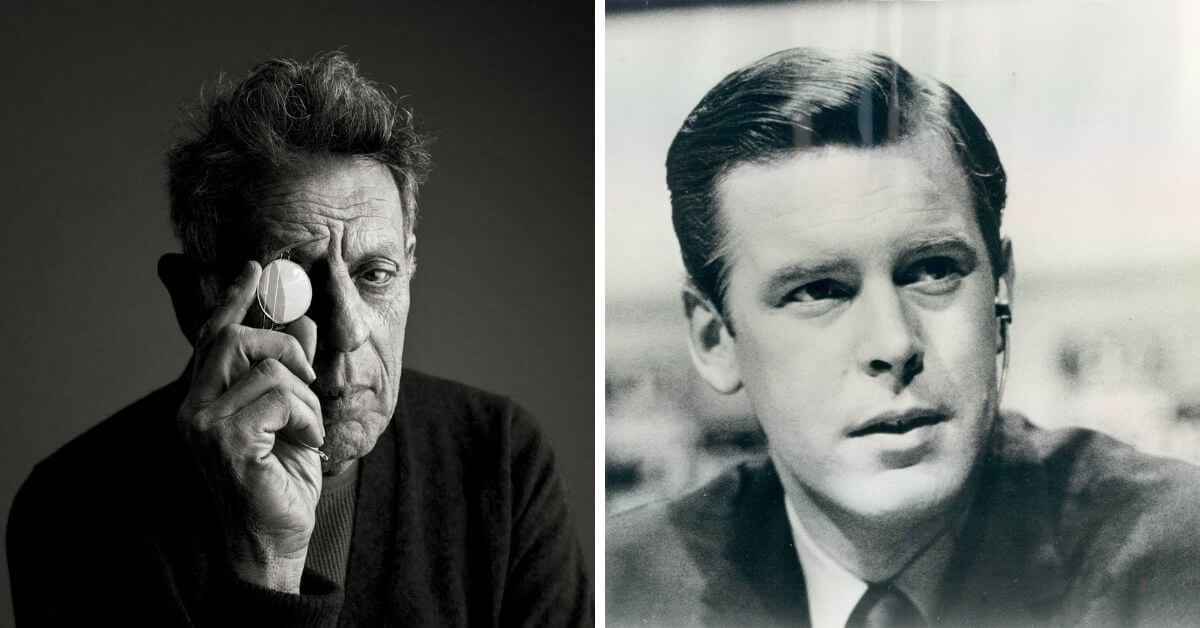

As those questions arose, the family of the late Peter Jennings approached the orchestra with the idea of commissioning a work in his memory. It was a perfect intersection of interests.

Peter Jennings, as Shelley notes, was one of the last universally trusted news anchors. “It’s an interesting entry point.”

Journalist Peter Jennings left a mark on his profession like few others. He came to represent integrity in journalism, looking for the truth rather than sensationalism. A Canadian-American dual citizen, he was named to the Order of Canada shortly before his death in 2005.

Philip Glass accepted the commission, inspired by the concept behind it.

“Philip was at the top of the list along with a couple of names,” Shelley says. “Wonderfully, he jumped to the project.”

Jennings’s legacy is the focus of the Philip Glass Symphony No. 13.

The Glass Symphony approaches the concept in the composer’s typically abstract terms. “I’ve had interesting discussions about the degree to which it’s connected to the theme. That’s always an interesting question,” Shelley says. He wonders about his choice of the symphony, a closed form with a cohesive structure, to express the theme of truth.

“Philip is deliberately vague about it in his notes — very spare,” he says, noting Glass is in that school of composer thought which allows for the creation of ambiguity.

The Program

The other works on the release, while they seem disparate, are unified by a common thread. “We built around it these other works.”

Nicole Lizée’s “Zeiss After Dark” was co-commissioned by NACO and the Toronto Symphony Orchestra for Canada’s sesquicentennial in 2017. The work has been performed by other ensembles since that time, and returns to be memorialized in this recording. Shelley says Lizée’s piece was inspired by the ideas presented in the Kubrick movie Barry Lyndon, namely, that truth can be elusive, even when it concerns past events that we think we can properly contextualize.

Shostakovich, under pressure to write what the Soviet regime considered a heroic victory symphony, came up short in public opinion of the time with his Symphony No. 9. In fact, the public and Soviet regime’s displeasure led to its banning, along with all of his work, from public performance.

At its premiere, the disapproving Soviet audience did not hear the unabashedly triumphant tones they were expecting. “Shostakovich — an artist who was told to tell the Soviet truth, but he tells a different story,” Shelley comments. “It’s a very snarky, sarcastic symphony.”

Erich Korngold fled the Nazis in 1934 for the United States, but initially hoped to return. He became an American citizen in 1943, and stayed in the US after retiring from his prolific career as a film composer in 1947. During the last decade of his life (he died in 1957), he composed several orchestral works, including the violin concerto, a symphony, and other pieces.

His violin concerto is probably the most popular of these. Shelley calls James Ehnes “a great Canadian artist”.

Yao’s original piece rounds out the program. “[He’s a] wonderful improvising poet and singer. He created a poem around the theme to do with race and identity and truth,” Shelley says.

“It was kind of a risky program to take down to Carnegie Hall,” he adds.

He’s glad in retrospect that it was what they brought to the venerated concert hall. After the New York performance, there were panel discussions around the issues raised. “We were able to draw the audience in the theme of art engaging with political questions.”

- Find out more about the recording and purchase/stream it [HERE].

Are you looking to promote an event? Have a news tip? Need to know the best events happening this weekend? Send us a note.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig Van Toronto e-Blast! — local classical music and opera news straight to your inbox HERE.

- PREVIEW | SUMMER OPERA LYRIC THEATRE Presents Handel’s Xerxes, Mozart’s Idomeneo & Puccini’a La Boheme July 26 To August 4 - July 26, 2024

- PREVIEW | YENSA Festival V.2 Offers Black Flames Performances & Other Ways To Celebrate Black Women In Dance - July 25, 2024

- PREVIEW | Canadian Talent Conspicuous In The Met: Live In HD 2024-25 Season - July 25, 2024