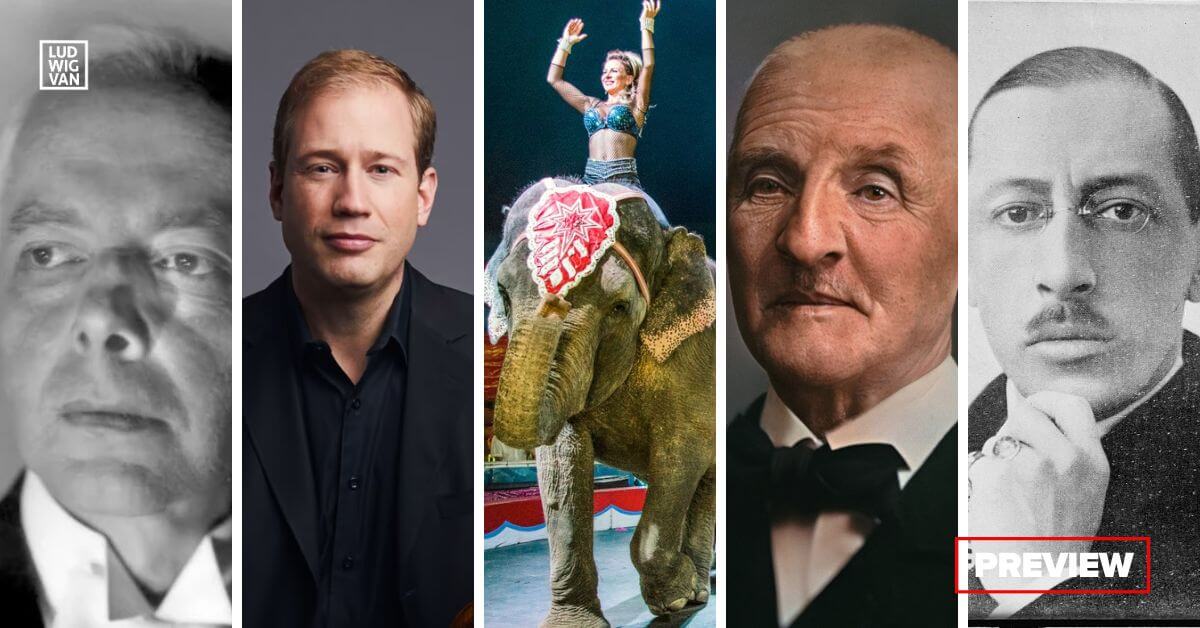

Kindred Spirits Orchestra and its conductor and music director Kristian Alexander have developed a reputation for imaginative programming that continues with The Greatest Show, their next concert. Daniel Vnukowski will host the performance that spotlights guest artist Jonathan Crow, concertmaster of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.

The programme for the concert on December 9 will, naturally, include a focus on the violin, with the addition of a Stravinsky piece that has a fascinating story behind it, and an epic Bruckner finish.

The Concert

The programme includes three works: Stravinsky’s Circus Polka: For a Young Elephant, Bartók’s Violin Concerto No. 2, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3.

Stravinsky’s Polka For Elephants

Igor Stravinsky wrote Circus Polka: For a Young Elephant in 1942. Ringling Brothers & Barnum & Bailey Circus had contracted choreographer George Balanchine to create a ballet for their elephant troupe in 1941. Balanchine called Stravinsky to ask him if he’d join the project.

As Balanchine (quoted in George Balanchine: American ballet master by Kristy, Davida, 1996) would recount, he called to ask Stravinsky to write a ballet for him. When the composer asked for whom, he answered “For a few elephants.” Stravinsky’s only question was, “How old?”

When Balanchine answered that the pachyderms would be quite young, Stravinsky agreed.

A substantial fee also, presumably, went some way towards persuading the Russian, who had newly arrived in the US. He wrote the work in just a few days for piano, completing it in February 1942.

However, by the time the ballet actually took to the stage with its elephant dancers, Stravinsky was no longer involved. Prolific film composer David Raskin arranged his piano score for organ and concert band. Balanchine had choreographed the work for a cast of 50 elephants (in pink tutus) and 50 dancers, starring his then-wife ballerina Vera Zorina and a cow elephant by the name of Modoc.

It premiered in April 1942 at Madison Square Gardens. While he didn’t attend the premiere, Stravinsky met Bessie, one of the performing elephants, and shook her foot. The audience was appreciative, but typical for Stravinsky, initial reviews were mixed, although he was no doubt accustomed to his music being labelled as “musical lunacy” by critics.

The 1942 concert band version, performed by the United States Marines Band:

A couple of years later, Stravinsky made his own arrangement for orchestra, which was premiered by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1944. Charles de Gaulle was reportedly a big fan of the work, and helped to spread its popularity in Europe.

On the balletic side, it’s been re-choreographed for an all-human cast by Balanchine himself, along with a new version by Jerome Robbins for the New York City Ballet. It has become a regular repertoire piece.

The piece is charming and whimsical, deceptively simple in some passages, but nonetheless retaining Stravinsky’s trademark harmonic language. Despite its title, only two bars of the work are written in a recognizable polka rhythm. It’s the rhythm, of course, that Stravinsky plays with throughout the composition. Stravinsky denied it himself on occasion, but many writers have pointed out similarities to Marche militaire No. 1 in D major by Schubert in the final sections of the piece.

Bartók’s Violin Concerto No. 2

Béla Bartók’s Violin Concerto No. 2, BB 117 was written from 1937 to 38, and was the composer’s only violin concerto performed during his lifetime (the “first” being published posthumously).

It was a turbulent time, and Bartók was affected by the rise of fascism, which made him a target in pre-war Hungary. He wrote it in three movements for violinist Zoltán Székely, who he had frequently collaborated with. It premiered in Amsterdam in 1939. The composer, fed up with the growing Nazi regime and its influence in his native Hungary, left for the United States soon after.

The concerto incorporates twelve-tone themes, while not written entirely in the twelve-tone technique. It has come to be valued as one of the greatest violin concertos written in the 20th century.

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 3

Anton Bruckner dedicated his Symphony No. 3 in D minor, WAB 103, to Richard Wagner. In fact, it’s sometimes called his “Wagner Symphony”.

The manuscript itself has something of a perilous history. When he completed it on December 31, 1873, he had two copy scores made. One version was given to the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in 1874, but while they rehearsed it, they eventually rejected it for performance. One version was lost in Leipzig during the Second World war. Revisions were made in 1874, 1877, and 1889, and there are several versions regularly performed today.

Today, it’s often considered his breakthrough work, but it was a notorious disaster for the composer at its premiere of a revised version in 1877. The original conductor died suddenly, and Bruckner, despite his inexperience with orchestral conducting, insisted on stepping in.

The musicians of the Vienna Philharmonic despised Bruckner, and heckled him throughout the rehearsals. (Notably, the orchestra had turned down Bruckner’s offered dedication of his second symphony.) The audience at the premiere laughed and shouted out insults, and many walked out between the movements — including a young Gustav Mahler.

While orchestras of the day rejected what they saw as an extremely difficult piece of music, the symphony that has been vindicated by time, and today, modern audiences appreciate its innovation and complex textures.

The Concert

The concert also includes a silent auction to support music education and the arts, a prélude: pre-concert recital by flutist Brooke Ramos White, and pre-concert talk. During intermission, there will be a Q&A with Jonathan Crow and Daniel Vnukowski, and a post-concert reception to mingle.

Find tickets and more information about the December 9 concert [HERE].

Are you looking to promote an event? Have a news tip? Need to know the best events happening this weekend? Send us a note.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig Van Toronto e-Blast! — local classical music and opera news straight to your inbox HERE.

- PREVIEW | SUMMER OPERA LYRIC THEATRE Presents Handel’s Xerxes, Mozart’s Idomeneo & Puccini’a La Boheme July 26 To August 4 - July 26, 2024

- PREVIEW | YENSA Festival V.2 Offers Black Flames Performances & Other Ways To Celebrate Black Women In Dance - July 25, 2024

- PREVIEW | Canadian Talent Conspicuous In The Met: Live In HD 2024-25 Season - July 25, 2024