Canadian Stage/Topdog/Underdog, written by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Tawiah M’Carthy, Berkeley Street Theatre, until Oct. 22. Tickets available here.

Suzan-Lori Parks’ 2001 celebrated play Topdog/Underdog is considered among the greatest American stage works ever written. For first time viewers, I know the play will pack a wallop. For repeat viewers, at least for this one, the edge has softened, so to speak.

I first saw the play at the Shaw Festival in 2011, and caught the production again when Obsidian Theatre brought it to Toronto. I think what really impressed me then, and still does, is that it was written by a woman.

When the Pulitzer Prize committee chose Topdog/Underdog as its 2002 winner, it called the play a fable, and if you are up on your Aesop, you know that a fable represents a bigger picture, in this case, the no-win situation of being an African-American man on poverty row. Parks herself said, “…the play speaks to who the world thinks you’re going to be, and how you struggle with that”. Needless to say, metaphors abound.

Booth (Mazin Elsadig) and Lincoln (Sébastien Heins) are brothers. Apparently, the names of the American president and his assassin were given to the boys by their father as a joke. For Parks, I assume, there is a terrible irony that both their namesakes are White men.

The brothers were left on their own when they were barely teenagers, when both parents, at separate times, walked out on them. Booth’s greatest skill is shoplifting, although he is currently engaged in trying to master the three-card monte trick that was Lincoln’s biggest money-maker. Lincoln dropped that hustle when his partner was killed. He was, as the expression goes, scared straight.

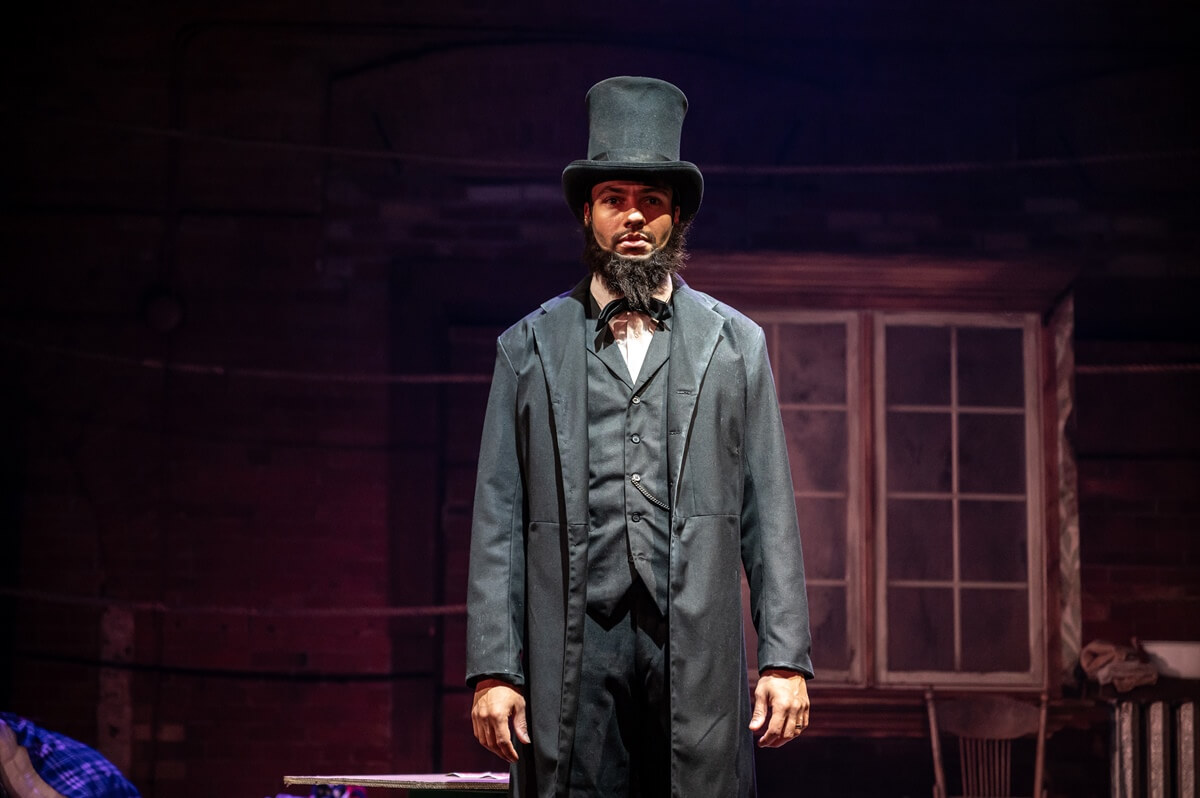

At the moment, Lincoln is sharing Booth’s shabby one-room apartment because his wife Cookie threw him out. His straight job is working in an arcade, dressing up as President Lincoln in white face, and letting people take pot shots at him with a cap gun. It is also his salary that’s keeping the brothers afloat.

Given their historical names, and the fact that Booth has a real gun, audiences know it is going to end badly right from the get-go. What Parks has given us to the run up of the violent ending — what fuels Parks’ narrative — is her driver behind the plot. The main theme is the loss of dignity that both brothers have to undergo, and have undergone throughout their lives. This is what is crushing their souls, and by extension, crushing the souls of African-American men in general.

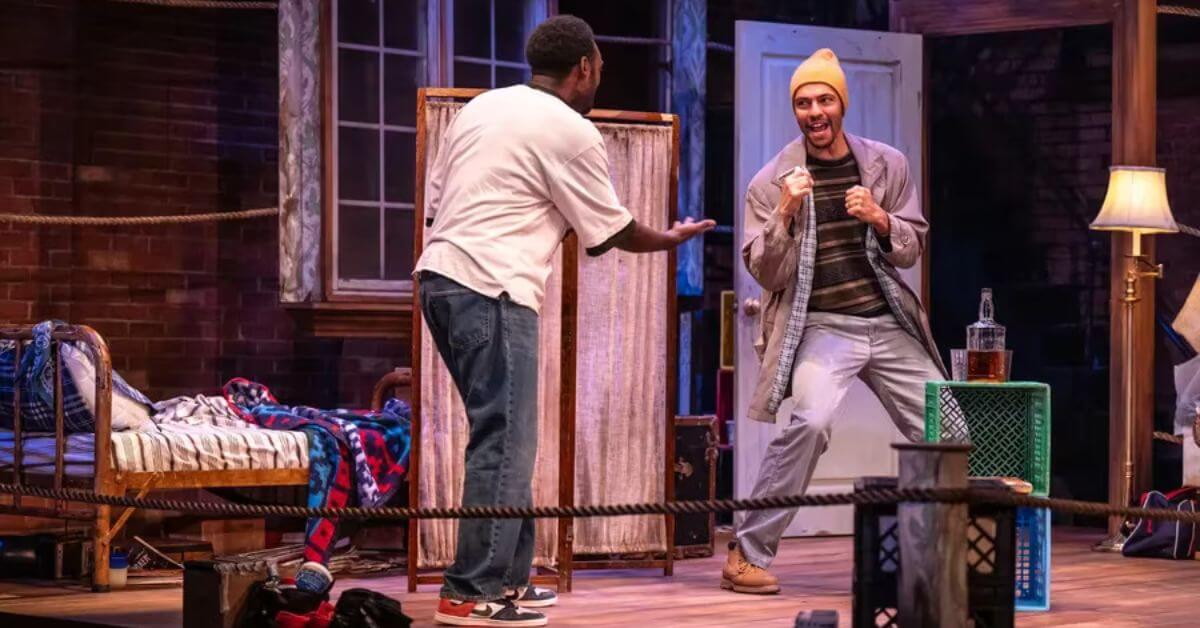

Although they survived abandonment at such a young age by relying on each other, they have always had a sibling rivalry, fuelled by a burning resentment towards each other and the world. Booth, in particular, suffers from this, and stirs up competition between himself and Lincoln with constant taunts.

Rachel Forbes’ clever set reflects the combative nature of their relationship. Booth’s flat is on a raised platform surrounded by ropes that evoke a boxing ring. Director Tawiah M’Carthy has had a bell ring, as if starting another round, before each new encounter. Jareth Li’s lighting contributes to the dingy atmosphere of the room.

Joyce Padua’s costume design is inspired. At one point, Booth takes out two complete outfits for himself and Lincoln that have lain hidden in his clothes — and that means two suits (jackets and pants), shirts, ties, socks and shoes. It’s astonishing how all this shoplifting has been jammed into what he’s wearing.

Elsadig’s Booth is wonderful as a man who is a human time bomb. His hair-trigger temper is indeed a very scary thing, and Elsadig keeps the audience on the edge of their seats, waiting for that bomb to explode. In his hands, Booth is a bundle of nervous energy that can lash out at any time — always taunting Lincoln, always provoking where he can. It is a very unsettling performance, but in a very good way.

I had some trouble with Heins’ low city/mean street accent because his drawl sometimes obscured words. That aside, however, his Lincoln has a sense of stateliness about him, seemingly even-handed, always trying to resist his brother’s baiting. When he does break out, however, the fierceness he has been trying to rein in comes out like a tornado. Then you see the taunting older brother he has always been, and the transformation is impressive.

As for M’Carthy’s direction, for the most part, he finds excellent characterization in his actors, although the pacing is sluggish at times. Nonetheless, Booth and Lincoln move easily around the room as if they belong. My one big problem is the ending, which I found a bit flat. It needed more verve.

In retrospect, one thing a repeated viewing does give this play, is a deeper look into how Parks has constructed her fable. The lives of Booth and Lincoln are not easy to witness.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.