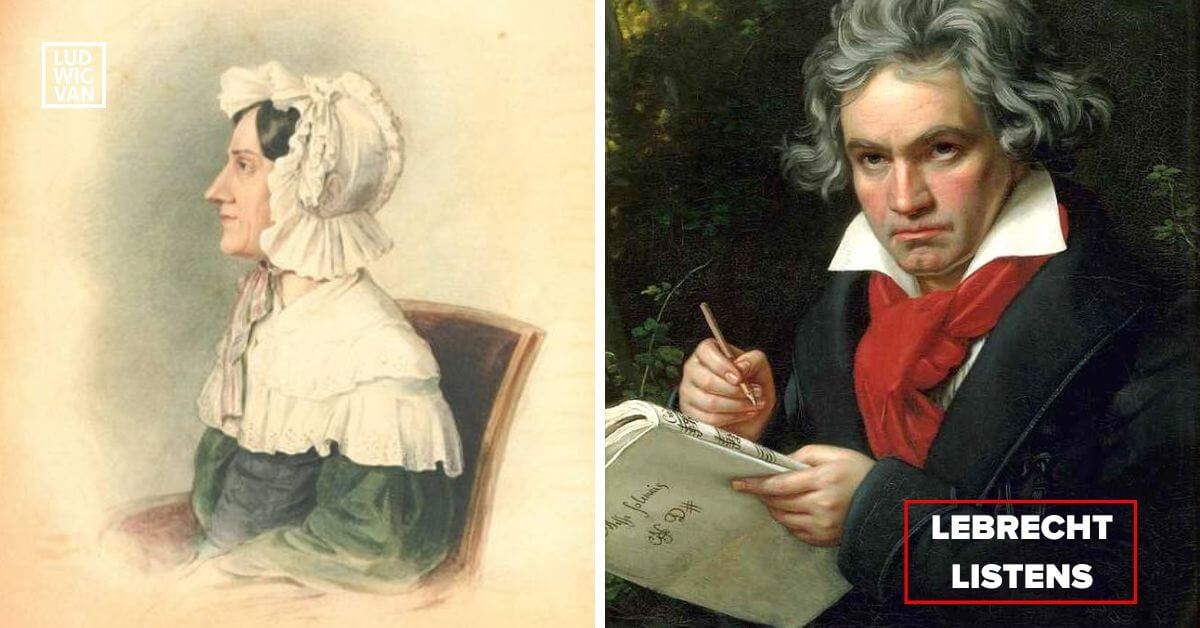

Nannette Streicher’s Fortepiano (Gramola)

★★★★☆

🎧 Spotify | Amazon | Apple Music

I can barely control my finger at the play button. This recording takes us as close to Beethoven in audible terms as it is possible to get. This is the sound that filled Beethoven’s room as he composed at least half of the 32 sonatas.

Nannette Streicher was his piano maker, and much more. She took his order for a Hammerflügel in 1812. Once it was installed, Nanette was in and out of his house every other day, disciplining his servants, helping with his accounts and generally doing her best to allow the most helpless of men to overcome his daily woes. People began to gossip about their intimacy, but 60 surviving letters and Beethoven’s conversation books show nothing beyond a respectable human connection that was important to them both. Beethoven got looked after, and Nanette learned how to improve her pianos in line with the challenging music he was writing.

Beethoven, for all that he trusted Nanette, bought his next piano elsewhere. Nanette, despite the snub, remained the truest of his friends.

So to hear an instrument that Nannette made in 1813, at the very outset of their connection, is a thrill that makes my fingers tremble. The model played here mouldered for decades in a warehouse until it was restored by Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum. Only two other Streicher instruments of this vintage survive. You can practically hear Beethoven’s fingers on the keys.

The music performed here by Ines Schüttengruber is not top-drawer. A ten-minute G-minor Fantasie by Beethoven (why not the Hammerklavier?) barely warrants ten minutes of attention. A Schubert Fantasie of 1811 is some way short of maturity. Works by Hummel, Moscheles and Vorisek amplify how far Beethoven was ahead of his time, and how little his contemporaries did to break barriers.

The clincher, though, is a pair of marches composed by none other by Nannette Streicher — trivial pieces written for a piano tuner or perhaps a child pupil, but revealing nonetheless an assertiveness and strength of character that appealed to Beethoven, and left him feeling less alone in the world in his years of deafness and pain.

Beethoven died in 1827. Nannette outlived him by six years. This recording is a remembrance of her indispensability to the great composer, her role in the making of the greatest piano works of the classical era.

To read more from Norman Lebrecht, subscribe to Slippedisc.com.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Klaus Tennstedt’s Conducting Genius Revealed In Live Radio Recordings - July 26, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS |Alexandra Dariescu And The Philharmonia Orchestra Tackle Clara Schumann & Grieg - July 19, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Yundi Gives Mozart A Revelatory Makeover On The Sonata Project — Salzburg - July 12, 2024