Toronto Theatre Roundup — Three Canadian Plays: Public Enemy by Olivier Choinière; Cockroach by Ho Ka Kei (Jeff Ho); Bad Parent by Ins Choi.

It just so happens that three compelling Canadian plays are making the fall theatre season a rich one, and all should be seen.

Collectively, they are on the stages of three of Toronto’s mainline theatres, and their substantive natures reflect the type of quality plays we expect from establishment culture. Two are world premieres, while the third is the first presentation in English. All are gilded by outstanding production values.

Even though all are inspired by aspects of the playwrights’ lives, they couldn’t be more different one from the other, yet they all present varying portraits of the dark side of the human condition — one using heightened realism, one written with humour noir, and one engaging in fantasy.

With playwrights Olivier Choinière, Ins Choi and Ho Ka Kei (Jeff Ho), CanLit can take its pride of place in the world arena of arts and letters.

What follows are my observations on what makes each of the plays a worthy theatrical experience.

Canadian Stage/Public Enemy by Olivier Choinière, translated and adapted by Bobby Theodore, directed by Brendan Healy. Berkeley Street Theatre. Sept. 20 to Oct 8. Tickets here.

Québécois playwright Olivier Choinière was awarded the Siminovitch Prize in 2014 for theatre, which is the equivalent of winning a genius award. His take on humanity is sharp, acerbic, incisive, provocative and surprising, the latter word describing the fact that you never know just how he is going to turn conventional plot devices upside down.

In his 2015 play Public Enemy (Ennemi public), Choinière makes as his central core the oft-used trope of a family dinner, apparently inspired by his own relatives. Translator and adapter Bobby Theodore has done a masterful job of replacing the Québécisms with an English Canadian perspective.

The adults include the matriarch Elizabeth (Rosemary Dunsmore), and her three middle-aged children, the bully James (Jonathan Goad), the feckless Daniel (Matthew Edison), and the seemingly passive helicopter mother Melissa (Michelle Monteith). There are also two younger family members, James’ sulky teenage son Tyler (Finley Burke), a bully like his father, and Melissa’s adolescent, over-sensitive daughter Olivia (Maja Vujicic).

Choinière has mandated that conversations take place at the same time, but the audience has to struggle. Depending on where you are seated, you’ll hear the closer discussion slightly better, but you’ll be distracted by words from the other, so you’ll never really get a strong grip on either.

From what I could make out, the topics bantered around by the mother and siblings include politics, CBC journalists, murderers, and conspiracy theories, and it becomes very clear that Elizabeth possesses a very conservative viewpoint, and is the quintessential grumpy old lady who mourns the passing of the good old days. The effect of this overlapping dialogue depicting ordinary dinner conversation is to lull the audience into a false sense of security.

The playwright’s next coup de théâtre is having Julie Fox’s wonderfully realistic dining room set revolve a third of the way to reveal the two young cousins in the TV room. We can also catch a glimpse of the dining room, where the four adults repeat the dialogue we have just witnessed, while we see what the youngsters are up to. There is a later second revolve to reveal a balcony off the TV room where important action happens.

We also learn why this dinner is taking place. James and Melissa are concerned that the jobless Daniel, who lives with his mother, is stealing from her. As in most families, money is the great crucible that poisons relationships.

There is yet another surprise that Choinière has up his sleeve. After a short pause, we are into Act 2, and a year has passed. This time the adults and the children are all at the table and there is an extra person, Daniel’s trashy, opinionated girlfriend Suzie (Amy Rutherford) who does most of the talking, spewing all manner of racial bigotry as she goes.

We also learn that the feisty Elizabeth from the first act is living in a home, and is a shadow of her former self. It would appear that Daniel still lives there. What have these siblings done to their mother, and to themselves?

How can these wonderful plot twists not fail to captivate? How can we not be fascinated by these rather unlikable people, who go through transformations that I will not reveal? How can we not see Elizabeth and her brood as a mirror of our own families to varying degrees? How can we not view Choinière’s damaged fictional family as a metaphor for society as a whole, and a dark one at that? And finally, how can we not be impressed by dazzling acting from a first rate ensemble?

Public Enemy is definitely a play unpleasant, but brilliant in its conceit. Kudos to director Brendan Healy who has done miracles with the pacing and tying the whole complicated structure together. As to just who or what is the public enemy, that is for each audience member to reason out for themselves.

And as a final note, I am in awe of Choinière’s creativity, particularly the way he manipulates stagecraft and theatrical conventions, which makes his plays unique.

Soulpepper, Prairie Theatre Exchange & Vancouver Asian Canadian Theatre/Bad Parent by Ins Choi, directed by Meg Roe. Michael Young Theatre, Young Performing Arts Centre. Sept. 15 to Oct. 9. Tickets here.

We’re now moving to a lighter note, albeit, not without its pain. Ins Choi is the writer who created the massive hit play-cum-TV series Kim’s Convenience, so it stands to reason that Bad Parent would be clever and entertaining, and it is.

Apparently, Choi was inspired by his own relationship with his wife, particularly the fact that the coming of their first child made, in his words, their marriage so difficult. Choi, and his wife Mari, have been together for 17 years in a loving relationship, yet Choi, in retrospect, wanted to come to grips with why a strong marriage was put under such a strain by a newborn baby.

And so we meet Nora (Josette Jorge) and Charles (Raugi Yu). Now the cast happens to be Asian, but this play could be performed by any racial group, unified or mixed, because it expresses a universality. The device that Choi uses is having the characters talk directly to the audience, and the first thing we hear about is how they met. They also talk about their lives, and correct each other when they perceive an incorrect fact — amusing, yet tense.

When baby son Mountain arrives (and how he got his name is another story), the couple become two rival monologues, each one telling their side of the story. It is almost as if Nora and Charles are each asking for our approval, wanting the audience to take sides.

Interpolated among the monologues are scenes between Nora and Charles, and two other people, also performed by Jorge and Yu. Jorge is Norah (with an H), the Filipina nanny Nora (without an H) hires when she goes back to work, while Yu is Dale, an understanding co-worker of Nora’s. The importance of Norah and Dale is to show us how relaxed Nora and Charles are with people outside their inner circle.

Each other’s behaviour really starts to bother the couple like a red flag to a bull. Charles hates the fact that Nora refers to Mountain pretentiously as an “18-monther” rather than being a year and a half old, while Nora is angered by Charles’ attempt to get Mountain to grow up faster than he should. For example, Charles gets a bed from IKEA, when Nora believes Mountain should still be in his crib. Nora goes to Mountain when he’s crying, while Charles thinks the infant should man-up and be allowed to cry it out. The growing disagreements between them is a constant irritation.

The main thing coming out, as the author’s intention, is that first-time parents are woefully adrift. A baby is born, and the couple leave the hospital with little idea of how to cope. Squabbling becomes their way of life. They may have thought they knew how to handle a newborn/toddler, but the stark reality of the situation is different than what they imagined.

Now in case I’m making the play sound too heavy, Choi has included some laugh-out-loud dialogue. As well, director Meg Roe has ensured chatty performances from her actors. They are talking to us like comrades in arms. There is seemingly no fourth wall, so we become very involved in their lives. While situations may be tense between the couple, they each approach the audience with sly manipulation.

Sophie Tang’s set is wonderful. The stage is like a child’s playroom that is filled with scattered toys. At the back are cases of shelves that look like cubbyholes that are stuffed with various baby and household items. Everything is bright and white, punctuated by colour. Deanna H. Choi’s sound design includes suitable bouncy music, giving the show a lighthearted feel.

Now as for the title, are we supposed to figure out which of Nora and Charles is the Bad Parent? Or does the Bad Parent concept stand for far weightier matters? Choi will never tell us directly. Suffice it to say, this is a play of home truths. Choi has captured the zeitgeist of new parenthood perfectly, and in a manner that is, ultimately, both charming and endearing.

Tarragon/Cockroach by Ho Ka Kei (Jeff Ho), directed by Mike Payette, choreographed by Hanna Kiel. Tarragon Mainspace. Sept. 13 to Oct. 14. Tickets here.

This is a play of immense imagination. Ho Ka Kei (Jeff Ho) has entered the realm of poetic symbolism to depict the tortured conscience of a guilt-ridden, fragile teenage boy (Anton Ling), apparently inspired by the playwright’s own life. As a play, Cockroach is filled with puzzling complexities that prey on the audience’s quest for understanding.

Boy, as the character is called, is an immigrant from Hong Kong, who along with experiencing the displacement of moving from one country to another, is also contending with his own homosexuality. We know something has gone terribly wrong in his life, almost making him suicidal. Cockroach is a coming of age play on the dark side.

The play is expressionistic, and we assume we are in Boy’s subconscious, as he copes with his trauma. Two characters populate his mind, and represent his fractured self. Each one is also a metaphor. First there is Cockroach (Steven Hao), who really is a cockroach, and then there is Bard (Karl Ang) who is an incarnation of William Shakespeare. Just how Ho weaves these three very diverse characters together is at the very fascinating heart of the play.

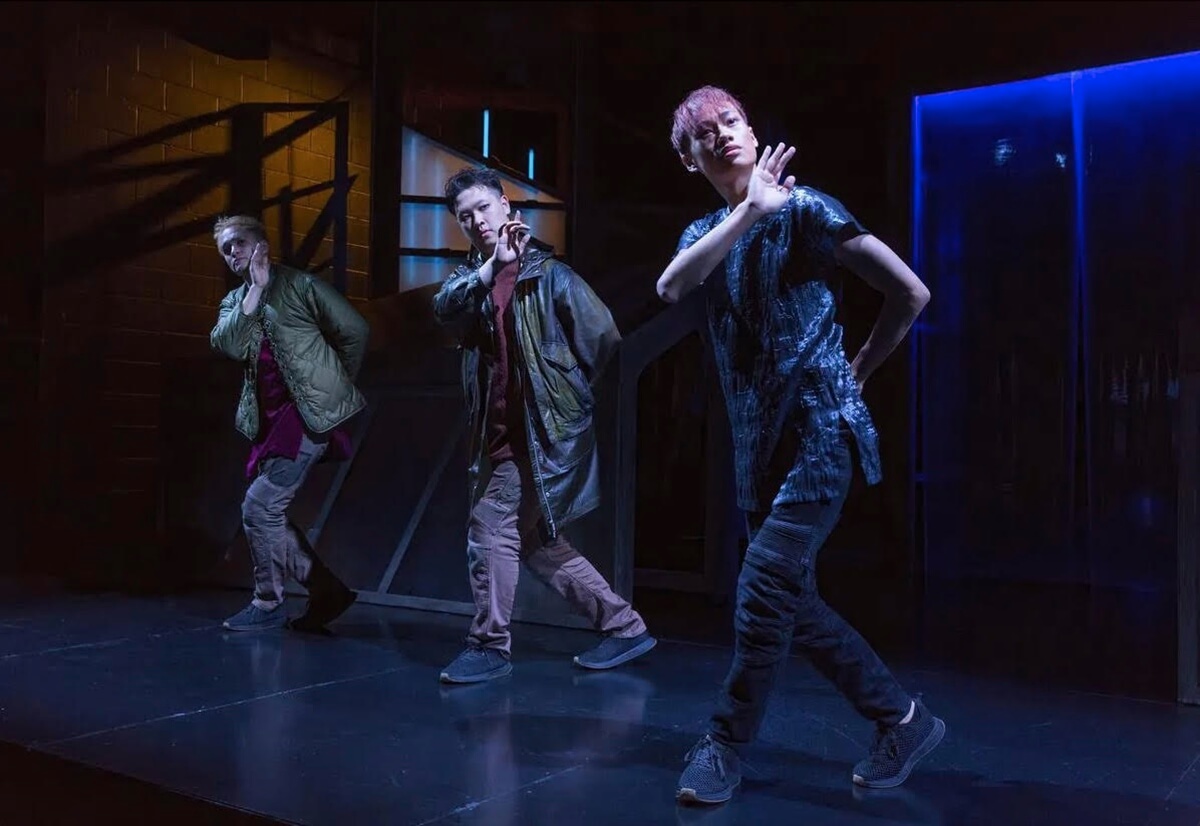

Gilding Mike Payette’s precise direction is the choreography of Hanna Kiel, one of my favourite dancesmiths. These young men are physically programmed to within an inch of their lives. Kiel has given them movement which at times reflects their words, at other times their feelings. This dance, as it were, contributes to the surreal nature of the piece, because no one is moving naturalistically. Payette obviously thought of this choreographic adjunct to his stage direction and he should be rewarded for his cleverness.

Christine Ting-Huan Urquhart has created a bleak, washed-out set that looks like a series of crowded roofs and staircases, which the cast travels up, down and all around. Deanna H. Choi’s sound design is one of menace, including a recurring abrasive noise which momentarily stops the cast in their tracks, as they all look to their right. Clearly something wicked this way comes.

Cockroach begins the play with a long monologue describing his life, which involves singer Whitney Houston’s wig and Boy’s dirty diaper. As well as telling us his autobiography in vivid and graphic detail, Ho has him opine on topics such as homophobia, anti-immigrant bias, racism, and Asian subservience.

Cockroach’s diatribe is sarcastic and angry, particularly over his species being used by humans to denigrate others. To be called a cockroach is the lowest of the low insult. As a metaphor, to me, he represents Boy’s perceived worthlessness.

We know Cockroach’s relationship with Boy, (he survived in his shit after all), but where does Bard fit in? Bard (Shakespeare) claims he is the foundation of the English language and when he joins Cockroach, he has great fun quoting all the lines and phrases he has given to English, replete with play and scene references. He also complains that he gets no rest because of the immortality of his quotes.

English, however, was the language of the colonial masters of Hong Kong, where Boy first encountered it. He has also had to grapple with English in coming to Canada. While Boy has embraced English, and has found solace in Shakespeare’s words, Canadians have used English to belittle him. On a subway ride, someone told him to go home. Bard, we can surmise, also represents oppression and racism.

It is Ho’s intention, I believe, that Boy conjures up Cockroach and Bard as instruments to teach him to survive. They give him comfort and the will to overcome his trauma, which, as we discover, involved an older gay man. Together Cockroach and Bard are suicide prevention.

The staging/choreography alone is worth the price of admission, as is the fine emotive performances from these young and talented Asian actors. I’m still thinking about the play long after I have seen it, trying to come to grips with its layers of meaning.

Theatre should provoke and Cockroach certainly does.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

- INTERVIEW | Actor Diego Matamoros Takes On Icon Walt Disney In Soulpepper Production Of Hnath Play - April 16, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Opera In Concert Shine A Light On Verdi’s Seldom Heard La Battaglia Di Legnano - April 9, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Lepage & Côté’s Hamlet Dazzles With Dance And Stagecraft Without Saying Anything New - April 5, 2024