Tarragon Theatre & Black Theatre Workshop/Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers, written and performed by Makambe K. Simamba, directed by Donna-Michelle St. Bernard, Tarragon Extraspace, Mar. 8 to Apr. 10 (in-person). Mar. 22 to Apr. 10 (streaming). Tickets available here.

Toronto has such a busy theatre scene that it is always welcome news when a highly regarded play that I missed the first time round is getting a second coming. Such is the run of Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers currently playing at the Tarragon Extraspace.

Our Fathers won both Best New Play and Best Performance by an Individual at the 2019 Dora Awards. That production was produced at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre by b current Performing Arts, a company whose specific mandate is “Black and Brown radical experimentation in content and form”, and Black, radical and experimental are certainly written all over Our Fathers.

What is interesting is that the play was nominated in the Theatre for Young Audiences Division. Needless to say, the Tarragon is aiming the run at the audience at large, and quite frankly, we older folk can always use a shock wave reminder that Black men and boys are being killed, primarily, because they are Black.

At the heart of Our Fathers is the shooting death on Feb. 26, 2012 of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, who was acquitted of Martin’s murder on the grounds of self-defence. Zimmerman was the neighbourhood watch at the gated community in Sanford, Florida, where Martin was visiting his father. The killing and acquittal made headlines around the world.

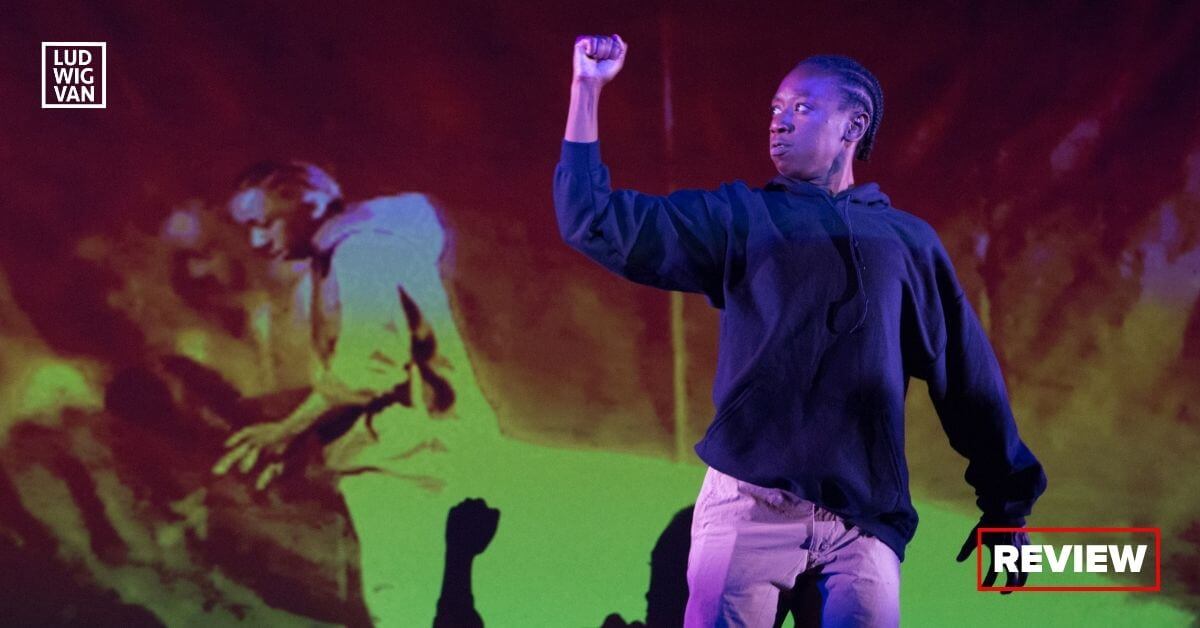

Makambe K. Simamba, who both wrote and stars in this one-person show, is a woman, but she makes a very credible 17-year-old boy. In fact, she has charisma up the ying-yang, and right from the get-go of Our Fathers, I found her to be a captivating performer.

She does not tell a linear narrative story of Martin’s killing, but takes quite a radical approach. We meet her first as Slimm (Martin’s nickname we find out later), a kid in jeans and a hoodie who has just died, and finds himself adrift in the afterlife without any idea of what to do. “If only I had an instruction manual,” he cries, and low and behold, such a book magically appears, thanks to set designer Trevor Schwellnus.

Journey to Your Ancestors: a step-by-step instruction manual the book is called, and so begins Slimm’s travels to his final resting place. Schwellnus is also responsible for the video design, which encompasses the entire back wall of the stage. The instructions that Slimm reads aloud from the book are also written out on the screen, accompanied by various graphic drawings.

Each step he must undertake triggers a memory in Slimm, and so we gradually learn about his friends and family, with Simamba playing all the characters. The only mention of Zimmerman is Slimm telling his girlfriend in a phone conversation that a guy is following him.

Martin was, in fact, just coming back from the store where he had bought Skittles (for his young brother) and a can of ice tea. Any audience member who followed the coverage of the killing will remember that much was made about these two items Martin was carrying, neither of which was life-threatening.

An impressive aspect of Our Fathers is just how cleverly playwright Simamba has very carefully thought through the steps in the manual. On one hand, they lead Slimm to his ancestors. On the other, they logically lead to memories. It is very, very smart playwrighting architecture. I also like the fact that Simamba has made Slimm a typical teenager. He comes across as just a likeable kid, which makes his death all the more senseless.

I did find the play a tad over-directed. While on the plus side, director Donna-Michelle St. Bernard has worked carefully with Simamba to draw strong portraits of both Slimm and those of his friends and family, his body movements have been meticulously choreographed down to a finger twitch, which becomes, in time, overkill. There is also a recurring sound (Diana Reyes is the sound designer) that announces when we are going into a memory, which I found a bit of spoon-feeding.

The play also takes a long time to get started, with Slimm going through a long, awkward physical routine while he becomes accustomed to the gravity of the afterlife. We also have a very long rap song intro with incomprehensible lyrics. (Maddie Bautista is credited with the original music.)

These cavils aside, no one can remain unmoved when Slimm is instructed by the manual to call on his ancestors, and thus Simamba embarks on recounting a seemingly endless list of men and boys who have been killed, citing their names, age and year of death. Some are known, but most are not. The names are not in any order, but cover a couple of centuries. How Simamba memorized that list is a triumph of the first order, and makes for devastating listening for the audience.

In several interviews, Simamba has referred to Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers as “a prayer for Black Life”. By the end of the play, the title has taken on a terrible irony, and becomes a threnody for all those Black lives cut short before their time.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

- INTERVIEW | Actor Diego Matamoros Takes On Icon Walt Disney In Soulpepper Production Of Hnath Play - April 16, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Opera In Concert Shine A Light On Verdi’s Seldom Heard La Battaglia Di Legnano - April 9, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Lepage & Côté’s Hamlet Dazzles With Dance And Stagecraft Without Saying Anything New - April 5, 2024