Digidance/Joe, choreographed by Jean-Pierre Perreault, film directed by Bernard Picard, livestream, Mar. 17 to 23. Tickets available through thepointofsale.com.

Jean-Pierre Perreault’s Joe is simply one of the greatest dance pieces ever created in Canada. After its first performance in 1983, the work was revived six times, and mercifully, the 1994 incarnation was captured on film by director Bernard Picard for Radio-Canada. It is that dancefilm, now 27-years-old, that Digidance is presenting as its second series offering. Yes, the film shows its age, but it is also a permanent record of an iconic choreography, and for that, we should be grateful.

This 1994 iteration is important for several reasons. For starters, Perreault considered it the final version of his masterpiece after tinkering with it through revivals in 1984, 1989, and 1991. Secondly, it was a pan-Canadian production — a joint venture between Winnipeg Contemporary Dancers, Toronto’s Dancemakers, and Montreal’s Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault. The 32 dancers came from all three companies and took the piece on a rapturous Canadian tour.

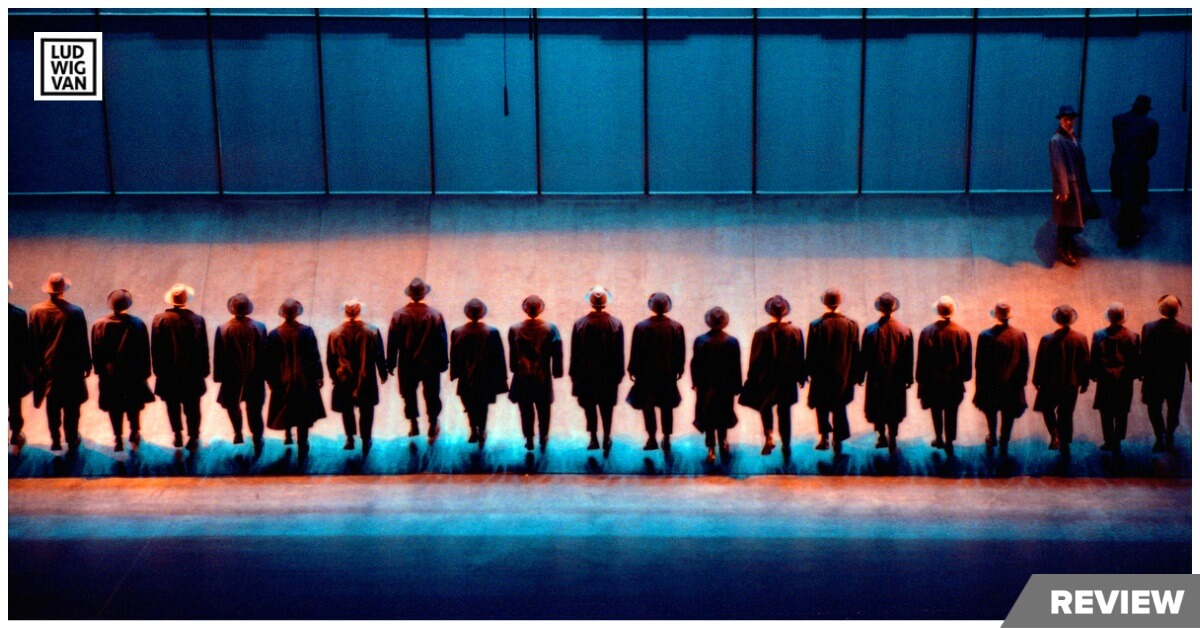

Yes, that is correct — 32 dancers — because Joe was the first of what would become Perreault’s trademark epic works. From then on, it would be armies marching across the stage. Perreault was taken from us too soon. He passed away from cancer in 2002, just 55 years old, but he left a legacy that embraces an immense imagination, and we have the testament of Joe to represent the singularity that was Perreault.

The work was originally set on 24 students (all women) from the dance program at UQAM (l’Université du Québec à Montréal), and this 55-minute school recital caused such a sensation, that Perreault created a professional production the next year. Over the various incarnations that followed, Perreault upped the dancers to 32 in number, added choreography to increase the time to 67 minutes, and brought in male dancers. The 1994 pan-Canadian Joe represents the final flowering of Perreault’s glorious choreographic gift to this country’s dance history.

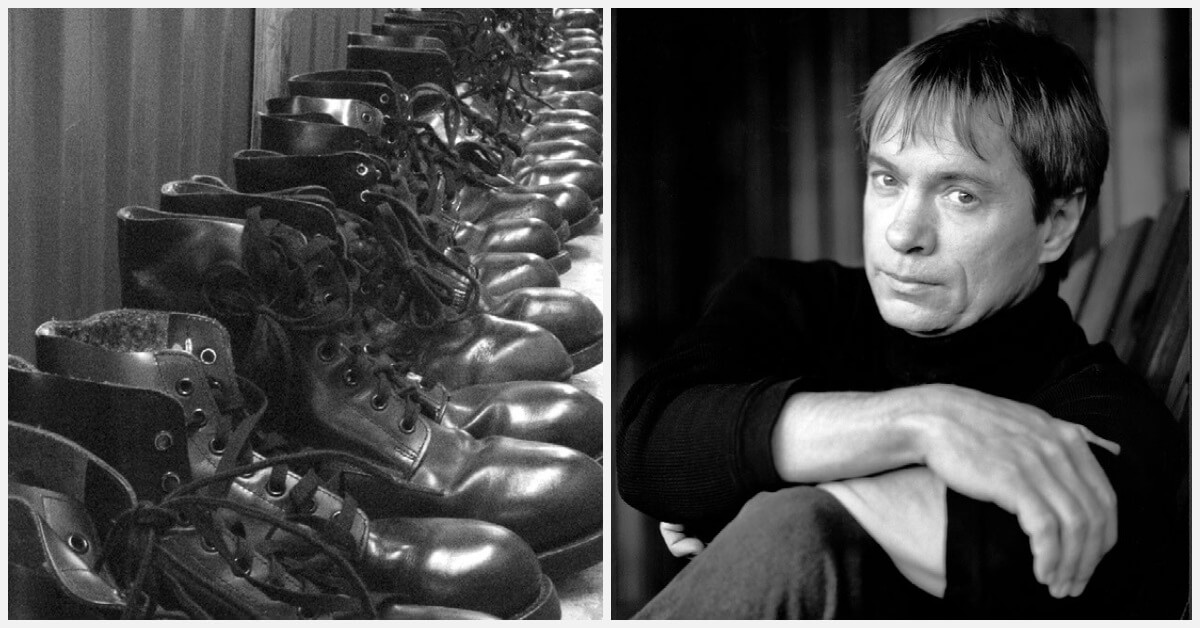

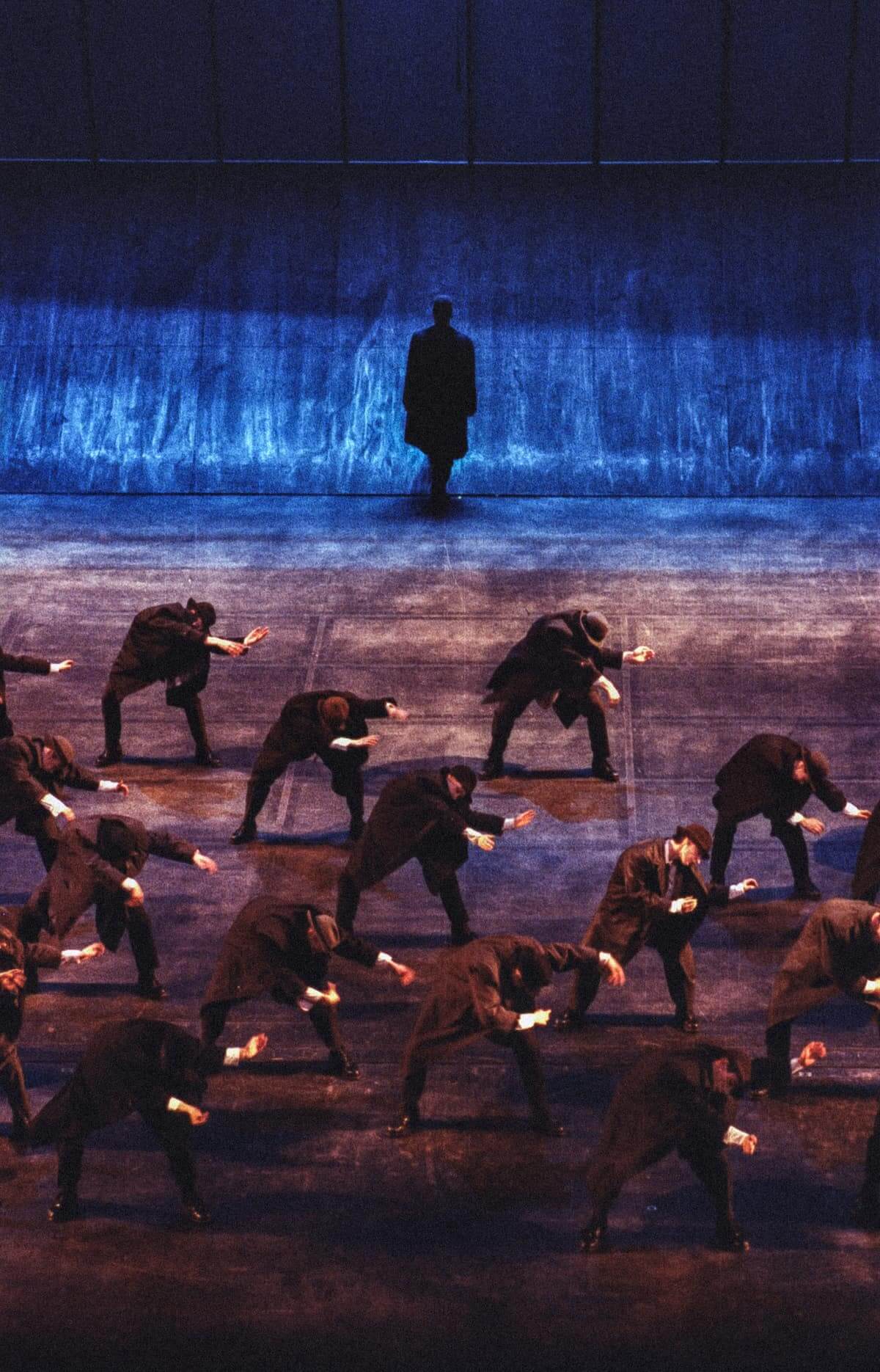

Perreault began as an art student, only coming to dance when he was 19 years old, but he never lost his artistic vision. For every one of his choreographies, he created the sets and costumes, working out everything in advance through drawings and paintings. In fact, these works of art are so interesting in their own right, that they had their own worldwide gallery exhibitions. The Joe paintings contain the various positions and clusters and movement patterns for the dancers as they work around the stage. The major set piece is a steeply raked ramp at the back that plays an important part in the choreography. The dancers climb it, but many slide down, only to climb again.

Imagine 32 anonymous Joes clad in men’s hats, raincoats, suits, ties, shirts and army boots. The boots are critical because they provide the soundtrack, also carefully worked out by Perreault. Philippe Overy was responsible for how the stage was amplified for sound, and he worked on both the original production and all the revivals that followed. It is impossible to tell the men from the women. Instead, we get a crowd of people, moving in tandem, with very occasionally, a single dancer breaking away from the crowd. Sometimes there is a duet break-away, even a quartet that separates itself out, but all are eventually swallowed up by the mass of Joes.

The title works for both English and French. In English, we talk about the ordinary Joe, so we understand immediately what Perreault is trying to say. The French derivation has an interesting background. Until Quebec broke the steel grip of the Catholic Church during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, every boy born in the province was given the first name Joseph, while every girl’s first name was Marie. The child’s first name on the baptismal certificate denoted gender, the second name honoured the child’s godfather, while the third name was the everyday name they would be called. For example, a certain former prime minister was christened Joseph Jacques Jean Chrétien.

When I first saw Joe all those years ago, I felt the overpowering influence of the herd, the mob, the mass, as the dancers moved with military precision through complicated choreographed manoeuvres. Through Picard’s film, however, I also re-discovered something that I had forgotten. There is an enormous amount of complex choreography going on. Joe is just not marching and making a lot of noise. There is dancing galore, and the closeup camera shows us just how intricate and varied the footwork is. We can also see the metaphors within the work, as each change of pattern represents a different aspect of society. Ambition, competition, aggression, fear, longing — they all are manifested within the brilliant choreography.

And there is something else. I remember interviewing Perreault before the 1994 pan-Canadian tour, and he said he wanted people to feel hope at the end. We had quite a discussion about my feeling that the sheer power of conformity destroyed any hope for me. Even though two people do finally walk away at the end, one lone figure is desperately trying to catch up to the others, and for me that was the stronger concluding image. Well, if Perreault were alive today, I’d have to tell him that I have come around to his way of thinking. This time, the piece was not just a condemnation of the pressure of conformity. What came across loud and clear was a striking portrait of the way society works as a whole. I saw the power of the collective, and the power of individual stirrings. The two dancers walking together off the stage at the end do represent hope.

Digidance is clearly dedicated to making a full evening of their online presentations. Crystal Pite’s program contained a documentary about her piece, and so does the Joe compendium, courtesy of Montreal dance historian/videographer Valérie Lessard. Unfortunately, we don’t have Perreault in the documentary, but we do have representative dancers from each of the seven productions as well as the various rehearsal directors who set the work. It is very clear that Joe had an enormous impact on everyone who either danced in it, or set it. Lessard’s inclusion of Perreault’s paintings for the piece are also a welcome illustration of the power of his genius.

I am absolutely thrilled that this Radio-Canada film has been resurrected to give countless new generations of dance fans an introduction to the work of Perreault through Joe. This is probably my fourth go-round with the piece, and seeing it once again confirms the timeless nature of the sweep and majesty of Perreault’s immense undertaking. I never forgot Joe over these many years, and either will anyone else who encounters this Canadian dance classic.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

- INTERVIEW | Actor Diego Matamoros Takes On Icon Walt Disney In Soulpepper Production Of Hnath Play - April 16, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Opera In Concert Shine A Light On Verdi’s Seldom Heard La Battaglia Di Legnano - April 9, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Lepage & Côté’s Hamlet Dazzles With Dance And Stagecraft Without Saying Anything New - April 5, 2024