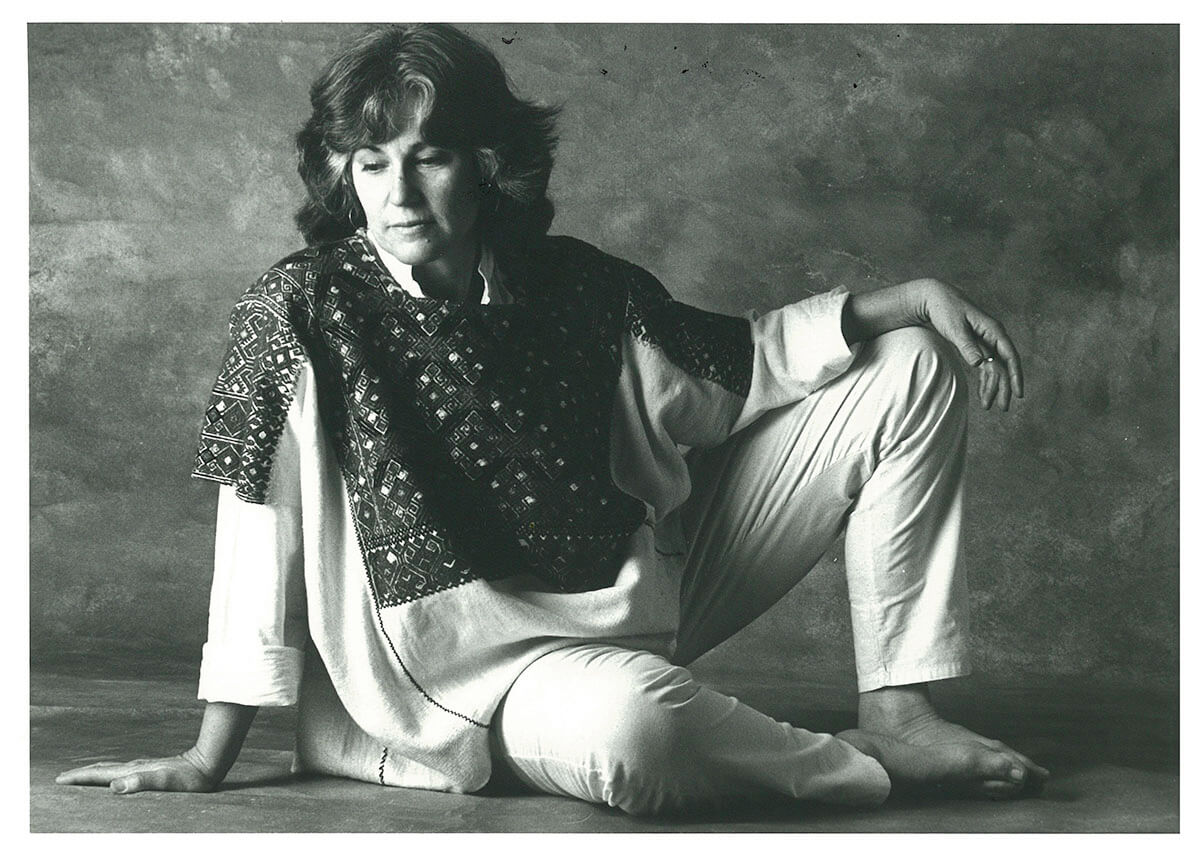

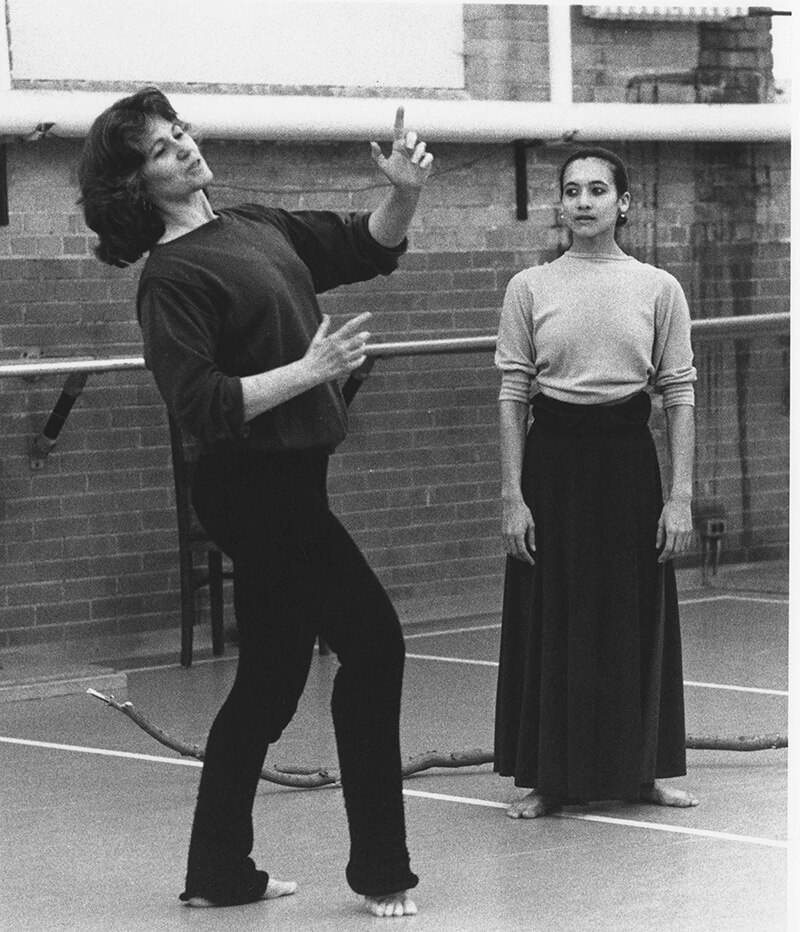

Choreographer, educator, writer, collaborator, producer, dancer – Patricia Beatty’s influence has touched generations of contemporary dance artists who work in every corner of this country. Inspired by American dance pioneer Martha Graham, Beatty became a pioneer of modern dance in Canada. She is credited as being among the first to introduce Graham technique to this country.

As a youngster, the overly energetic, Toronto-born Beatty was sent to Jean Macpherson’s creative dance classes for children, followed by ballet studies with Gladys Forrester and Gweneth Lloyd. As Beatty told me in a 1998 interview, she felt hemmed in by ballet’s autocratic system. Her liberation came when she attended Bennington College in Vermont whose liberal arts curriculum stressed creativity. Although she had never seen contemporary dance, Beatty enrolled in the dance program as a performance and choreography major under teacher William Bales. She also attended the summer programs at Connecticut College, where the New York modern dance luminaries gathered.

After graduation she studied at the José Limón School, but switched to the Martha Graham School of Contemporary Dance, mentored by Bertram Ross and Helen McGehee. As she said, “I became enamoured with the modern dance principle of internal, organic movement. I changed from Limón to Graham technique because I needed to be more grounded than was possible with the lighter Limón style.”

Beatty’s major New York career was with Graham acolyte Pearl Lang Dance Company (1960-1965), but she also worked with Mary Anthony, Sophie Maslow and Lucas Hoving. Through these major figures of American modern dance, Beatty found the wonderful mix of passion and artistry that anchored her choreography’s creative process. Said Beatty: “I also discovered that as a choreographer, I’m a painter. I move dancers across a canvas.”

Beatty’s own dance works were intense, dense, enigmatic, spiritual and profound. Her themes were about the subconscious, sexuality, the eternal feminine and the mysteries of nature. More akin to pieces of art than dance, Beatty’s choreographies were enhanced by collaboration with composers and designers. I remember sitting in stunned silence after experiencing her solo First Music (1970). On the surface, it was a karmic journey to serenity, but beneath the surface, was a complete surrender to sexuality. The dichotomy between purity and carnality left me spellbound.

During her years in New York, Beatty had become increasingly disenchanted with what she called, the circus lifestyle. In 1965, she returned to Toronto as a Graham missionary. “New York didn’t need my work,” she declared, “Toronto did. My aim was to present a new style of dance where women were elegant, dignified and strong.” She first opened her school where most of her students were ballet rejects. After training them for two years, Beatty felt ready to launch her company, and in December, 1967, the New Dance Group of Canada gave its first performance. The major work was Momentum, a complex psychological piece based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth, which mirrored Graham’s archetypal themes.

Participating in that first concert as guest artists were Toronto native and former Limón dancer David Earle, and Peter Randazzo, a former Graham company member. The two choreographer/dancers had come to Toronto thinking to start a modern dance company. Beatty joined forces with them in 1968 to launch Toronto Dance Theatre and School of Toronto Dance Theatre, and the rest, as they say, is history. TDT and the school remain in the top tier of both performance and training in the country.

The elegant, stately Beatty continued to dance until she was 47, finally leaving the stage in 1983. In 1993, she gave up her position as TDT resident choreographer to work independently on special projects. Beatty has always been concerned about dance history and legacy, and in 2002, she co-founded Toronto Heritage Dance Company, which remounts Canadian classics. A supremely gifted teacher, Beatty continued as a mainstay at the TDT school training students in technique that was Graham-based, but infused with her own life experience, and which came to be known as Beatty/Graham. Her book Form without Formula: A Concise Guide to the Choreographic Process (1985) is considered a classic and has never been out of print.

Beatty was an avid collector of contemporary art and among the special concerts she produced was the exquisite Painters and the Dance (1983), which featured her choreography set against the designs of Gordon Rayner (Raptures and Ravings), Graham Coughtry (Emerging Ground) and Aiko Suzuki (Skyling). She also was a champion of Canadian composers, commissioning original scores for most of her works. Beatty had a particularly fruitful collaboration with composer Ann Southam. The aforementioned Skyling and Seastill (1979) are among Beatty’s delicate and sensual renderings of the majesty of nature.

In the 1990s, Beatty turned her focus to creating choreography dedicated to the sacred feminine. In 1993 and 1995, she presented these gorgeous, rapturous choreographies in concerts called Dancing the Goddess. For Beatty, the goddess archetype represented balance, nurturing, healing and reverence for the sanctity of the body and nature. As she explained to me at the time, “Dances made in the name of the sacred feminine can be a positive force in the world. I’m interested in what defines life, not what takes it away.” For example, Mandala (1992) is a magnificent coming of age ritual as older women prepare young girls for life. In fact, Beatty equated Christianity and patriarchy with fascism. Her sacred feminine works were designed to confront our deepest, darkest emotions and liberate them from man-made restrictions.

Beatty always felt that her career was one small cog in a cosmic wheel much bigger than herself, a universe where modern dance, the sacred feminine and loving the planet are the most important things. Said Beatty: “In dance, both the dancer and the audience go through a transformation to a new level of awareness. There is no difference between the audience and me. We’re in life together.”

As recognition of her contribution to dance, Beatty was named a Member of the Order of Canada in 2004. In its citation, the award acknowledged Beatty as one of Canada’s most influential figures in modern dance, noting, in particular, her expanding the traditional boundaries of form, and being among the first to synthesize visual art and music into her creations.

In leaving this tribute, let us give the last word to Trish, as she was universally known. When I asked her once to sum up her dance ethos, she replied: “I don’t want to entertain. I want to compel.”

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.