One commonality that exists among all the world’s ballet companies is the company class. In that hothouse atmosphere, teachers craft exercises that push, pull and prod the dancers to warm-up their bodies before a strenuous day of rehearsals and performances. Says Christopher Stowell, the National Ballet’s associate artistic director, “The company class re-examines the elements of technique while addressing strengths and weaknesses. It is vital for the physical and mental well-being of the dancer. The stronger the technique, the less likely that a dancer will injure themselves.”

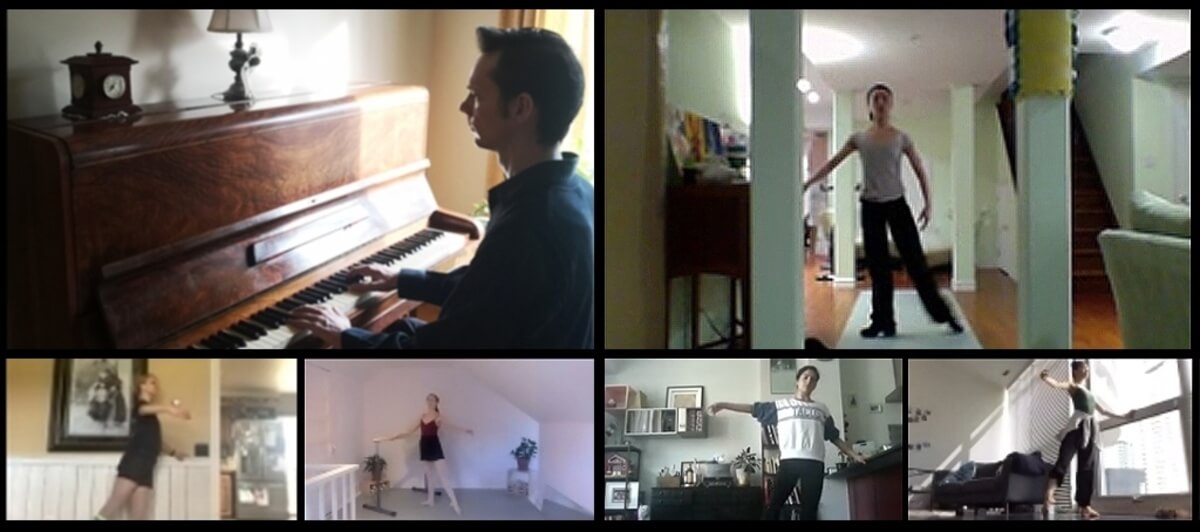

What, then, happens to company class when all the dancers and teachers are confined to their homes? Ballet dancers can never let their technique slide because that very fundamental ballet vocabulary is the crucible of their art. Only with a strong technique imbued in the body, can a ballet dancer take to the stage to express artistic freedom. Thus, when it became clear to the National that stay-at-home would be the new normal, a virtual company class had to be created. It turned out to be easier said than done.

For the model, the National looked to the online Worldwide Ballet Class, which had been started by friends of Stowell from his former company, San Francisco Ballet. In fact, Stowell had been asked to be one of their guest teachers. WBC was conceived when Californians were ordered to shelter in place. Using Zoom as the platform, the classes maintain technique training for the international ballet community as a whole, under the tutelage of a wide array of guest teachers. In designing its own class, the National developed the concept in consultation with the dancers and the wellness team. The latter were involved because of the all-important issue of safety, which will be discussed later in the article. (And here’s a curiosity for you. Company class is not mandatory but optional. Alas, the explanation is far too long for an already overlong article.)

The National was already using Zoom for meetings that had been set up by Jennifer Bennett Darbyshire, executive assistant to the artistic director and administrative manager. (She had some familiarity with Zoom because she is a participant in a weekly call involving her girlfriends from university.) Thus, it logically fell to Darbyshire to set up the Zoom account for the company class, which she would therefore host. Problems, however, were immediately apparent. “I’d open the company class,” she explains, “but then I’d turn off my video and audio so I could do my own work. Early on, we could see that a full time host was needed to be a facilitator and trouble-shooter. That’s when the stage managers became involved.”

According to Stowell, Darbyshire, stage manager Jeff Morris, and music director and principal conductor David Briskin, setting up the virtual class necessitated a series of technical refinements. The agent provocateur, as it were, is the thorny fact that company class is accompanied by a live pianist. Zoom is a platform designed for meetings and teleconferences, employing one speaker at a time, and not a teacher and a pianist in two different locations. Says Briskin: “The sound quality of the piano on the Worldwide Ballet Class is not great, so we were determined to give our piano a more natural sound. In fact, Jeff is compiling a best practice manual for holding a class on Zoom with a live piano.”

Among Zoom settings, there are noise suppressors designed to cut out background sounds like a dog barking, or a washing machine, or a noisy office. As well, Zoom can automatically adjust volume control. For the National’s company class, however, Morris and Briskin discovered that these functions should be shut off in order to optimize sound. “It means there is less conflict between the voice of the teacher and the piano,” states Morris. “The teacher can even talk over the piano without cutting it out, but we recommend that the teacher remain silent when the piano is playing. Anything coming out of computer speakers is never going to sound great, but we can get the piano to sound better in terms of balance and volume by shutting these settings off.”

Perhaps the biggest refinement has to do with what everyone calls the “delay”. Explains Briskin, “Everyone’s Internet connection runs at different speeds. The variables are endless, so if the piano begins to play immediately after the teacher stops talking, some people will be out of sync. This would not be a problem if the teacher and pianist were in the same room. For that reason we discovered that the pianist has to wait at least two seconds after the teacher stops talking, so that everyone’s Internet can catch up.” In fact, Briskin continues to monitor part of every company class to check on the balance between pianist and teacher, as well as the quality of the sound. So integral is this issue in the hearts of the music department, that according to Darbyshire, the National is actually in conversation with Zoom technicians to make the experience of company class the best it can be.

One could ask, therefore, why live music if it is so problematic? Enter the ballet company pianist. This special breed of artist not only plays for company class and rehearsals, they are also called upon to perform virtuoso solo work should a ballet score demand it, such as a piano concerto. For company class, more often than not, they are composers, instantly creating music in the precise tempo that an exercise set by the teacher requires. Recorded music, which is fixed, can never approximate what a ballet pianist does. With recorded music, a teacher has to make the exercises fit into the notes, rather than having a free flow of melody that fits the exercise.

Says Briskin, “Our class pianists are invaluable partners in this daily ritual. Their melodies support the combinations that are taught. Simply by watching the teacher describe and demonstrate the steps, the pianist translates what they see into the metre, tempo and mood that will suit the particular combination. During the exercise they can make tempo adjustments, add a phase, or bring the combination to a close with little more than a gesture or glance from the teacher. A skilled class pianist is as responsible for the quality of the ballet class as is the teacher.”

Zhenya Vitort is one of four National pianists. When she is in the studio, she can usually pick up by instinct the tempo that the teacher needs. The current remove means that she is less likely to catch the tempo by intuition. Nonetheless, the music must play on, and in this new reality, Vitort depends on the teacher to be very specific. “An exercise usually takes 32 counts,” she says, “and the teacher has to clearly indicate the time signature. I play an introductory vamp, and the exercise begins. The combination is usually repeated several times in different directions, like executing tendus to the front, side and back. To indicate the change of direction to the dancers, I can modulate to a minor key, or elaborate on the melody to make it seem like a separate section.”

To improve on her own sound output, Vitort uses an audio interface (Zoom H6 Handy Recorder), which is a machine that compresses sound and makes it digital. “I connect via audio settings in Zoom,” she explains. “My electric piano is plugged in to the computer through H6. Once I join the meeting in Zoom, there is an audio option to choose the input/output source. Instead of using the built-in microphone in the computer, which is set by default, I choose ‘H6’. That is the sound of my keyboard and this becomes my ‘voice’ in the meeting. The use of an audio interface really improves the sound quality. My husband can drill away in the basement or talk on the phone while I play the ballet class. He will not be heard by anyone in the zoom meeting.” And how does she feel about the virtual class in general? “I love the idea,” Vitort says, with her tongue firmly in her cheek, “because I can wear my pajamas.”

Before the 11:15 am class, Darbyshire opens the Zoom account, but immediately designates the stage manager and the teacher as co-hosts. She then retires from the fray. The pianist also checks in about ten minutes early. Says Morris, “Everyone has a different system. There are electric pianos, electric keyboards, and acoustic pianos. The teachers use Bluetooth headsets with mics, or other mics, or their own voice. That’s why there has to be a careful audio check at the beginning.” Stowell is particularly concerned about the placement of his computer in his living room so that his whole body can be seen, and relies on the host to make sure it is. The host also makes the teacher the dominant image for all participants through Zoom’s spotlight function.

Most of the company, like principal dancer Sonia Rodriguez and second soloist Kota Sato, check in early, and using gallery view, which shows a thumbnail picture of everyone who is attending, they catch up with their colleagues. “It’s the only time we get to see each other,” says Sato. Before the class begins, the dancers mute their sound. If they want to ask a question, like a repeat of the teacher’s instructions, they use the chat function, which the host then conveys to the teacher. Everyone watches the teacher for an explanation and demonstration of the combinations, but when the class executes the exercise, some elect to keep gallery view to watch the others, some use their video as a mirror to watch themselves, and some turn off their video so they won’t be seen. For those who leave their video on, Zoom’s pin function allows the dancers to move away from the teacher and choose their own dominant image or images from among their colleagues. The pianists usually keep the teacher as the dominant image, and then move to gallery view so they can follow the energy of the dancers.

Inevitably, there are technical issues, such as the music cutting out, or someone’s Internet connection making the picture choppy, or the teacher’s screen freezing, all of which the host attempts to correct. “These glitches are just part of the challenge,” says Rodriguez. Morris relates that you never know when a curious pet or a rambunctious child is going to enter the picture. “I’ve sure seen a lot of dogs,” he says. Although the company class has never been Zoombombed, the hosts are ready if a stranger/hacker enters their cyberspace. The interloper can be excised through the administration function, or more benignly, put in Zoom’s Waiting Room while they are checked out.

The company class is made up of two parts. The first includes exercises at the barre, followed by exercises in the centre. As Stowell explains, compromises have had to be made. “Very few people will have a sprung floor at home to cushion impact, so that limits rigorous jumping because the dancers could injure themselves landing on a hard surface. Slippery floors can also be particularly dangerous for point shoes. As well, in small spaces you can’t do exercises that are designed to cover a wide area. I can’t give large moving combinations of steps, or steps requiring more virtuoso technique, or complex turns. Therefore the barre exercises are longer than usual because we’re limited in the centre. The basic tenets remain the same. Warming the body. Working on technique. Making the muscles strong and supple. Ballet is impossible to be done perfectly. The rules are extreme, so I’m using this time to go back to strict academic correctness. The exercises are rudimentary and exacting, and designed to help the dancers grow in physical strength. I also end with a reverence, which I usually don’t do. This group bow means we finish together, like a community of dancers.”

Stowell has also noticed that he has to be crystal clear when describing a combination, even when demonstrating the exercise, because the pianist and the dancers are not there with him. As for the dancers being eager for corrections, he admits the difficulty of giving individual ones. Says Stowell, “Rather, I give general corrections to the whole group, such as, this combination is about the alignment of the spine, or that one deals with the articulation of the lower legs.”

Sato’s commentary on Stowell’s back to basics teaching is that it’s like a return to ballet school. “This class is the only ballet we’re getting,” he says, “so we can focus on every detail of positioning and placement. When we are in rehearsals, the teachers often introduce into the class choreographic technique related to the production, but this virtual class is pure ballet.” For her part, Rodriguez tries to compensate for the missing jumps and travelling turns by adding resistance while she is performing the combinations at the barre. Says Rodriguez, “I use therabands to create tension, and sometimes little weights. In other words, I make the barre more challenging to compensate for the loss of centre work.”

Because the floors in various people’s homes are bad for ballet, the National came up with an ingenious solution to give the dancers a decent surface to train on. Says Morris, “My production director and I cut out 6’ by 5’ rectangles from bits and pieces of off-cuts of dance floors. We also cut up retired floors that we had used for educational outreach. We never throw anything out because you never know when you have to cover steps or platforms. We asked how many dancers wanted the floors, and then we rolled them up, and left them in the foyer of the Walter Carsen Centre to be picked up, along with a box of floor tape.”

Morris has witnessed dancers using chairs, staircase railings, and in one case, a quilt and blanket rack, to substitute for the barre. In Sato’s small apartment, his barre is the counter that separates his kitchen from his living room. The vinyl floor he got from the company is taped down on the living room side. “It’s become part of the décor,” he laughs. Rodriguez lives in a house and has a workout room in her basement where her vinyl resides. She is lucky enough to actually own a portable barre. “It was a fluke,” she says. “I stumbled onto Facebook Marketplace that I never knew was there, and saw an ad for a portable barre. It was a long drive, somewhere in Burlington, I think, so it was sort of an adventure picking it up.”

There are 66 dancers in the company, excluding the character artists. Since company class began on April 6, the average number of attendees is 25 to 30 dancers. Both Rodriguez and Sato take class elsewhere from time to time, particularly the Worldwide Ballet Class. Says Stowell, “The dancers are likely taking advantage of the many other options available right now on the Internet, or they may prefer a different time of day for their work out. There is talk now of recording the company classes and making them available to the dancers so they can use them as a training guide at a time that is convenient to them.” And Morris adds, “Recording the livestream would benefit dancers who, for reasons such as their time zone or Internet speed, are having trouble participating in the classes in real time.”

Rodriguez, ever the realist, sums up the impact of the virtual company class in the following. “Is it ideal? No. Is it making the best of a bad situation? Yes. Is it helping to motivate the dancers physically and mentally? Yes. Is it creating a sense of community? Yes.” In other words, that’s three yesses to one no, which puts it into positive territory. As well, the class is having an effect on the Zoom platform itself. The best practice book that Morris is compiling is a manual that will be shared widely. As Briskin says, “We’re pushing boundaries with our innovations.”

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- INTERVIEW | Actor Diego Matamoros Takes On Icon Walt Disney In Soulpepper Production Of Hnath Play - April 16, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Opera In Concert Shine A Light On Verdi’s Seldom Heard La Battaglia Di Legnano - April 9, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Lepage & Côté’s Hamlet Dazzles With Dance And Stagecraft Without Saying Anything New - April 5, 2024