A strong cast, an impeccable orchestra, and fanciful staging make COC’s Rusalka a not-to-be-missed highlight of the season.

Sondra Radvanovsky (Rusalka); Pavel Cernoch (Prince); Štefan Kocan (Vodnik); Elena Manistina (Jezibaba); Keri Alkema (Foreign Princess); Anna-Sophie Neher (First Wood Nymph); Jamie Groote (Second Wood Nymph); Lauren Segal (Third Wood Nymph); Matthew Cairns (Gamekeeper); Lauren Eberwein (Turnspit); Vartan Gabrielian (Hunter). David McVicar (Director); COC Orchestra and Chorus, Johannes Debus (Conductor). Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, October 12, 2019.

Of the ten operas composed by Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904), Rusalka is by far the most popular, and the only one that has gained a spot in the standard repertoire. As such, it can be considered the iconic “Czech Opera.” Available performance statistics (2004–2018) has it in 38th place in popularity among all operas, with 1,573 performances in 265 productions worldwide, beating out Smetana’s The Bartered Bride (51st), and the two most popular Janacek operas, Jenufa (68th) and Kat’a Kabanova (98th).

Rusalka is based on the Slavic fairy tale of a water nymph who falls in love with a prince and longs to become human, with tragic consequences. It bears a strong kinship to Undine by German poet Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, as well as to Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. The opera premiered in 1901, but didn’t come to this side of the pond until 1975, when it was staged by the San Diego Opera. It reached the Met in 1993. I have fond memories of the evocative, rather old-fashioned Met production, starring Czech soprano Gabriela Benackova.

A belated Canadian premiere took place at the COC in February 2009, in a serviceable production from Theatre Erfurt, quite good singing but undone by some wild staging from Dmitri Bertman. This time around, a very handsome production comes from the Lyric Opera of Chicago, directed by the highly regarded Sir David McVicar. Set designer John Macfarlane has created a naturalistic fantasy world that suits the fairy tale nature of the story.

Compared to the minimalist Robert Wilson Turandot, this Rusalka may appear traditional, but it has its share of directorial quirks. In the opening scene, an unhappy (and drunk) Prince rejects the Foreign Princess, takes some unknown substance, passes out and enters into the realm of fantasy. The implication is that this story is told as a flashback. To my eyes, McVicar’s approach is “Verismo Czech Style,” rather over-the-top and somewhat in-your-face, not particularly subtle but undeniably melodramatic.

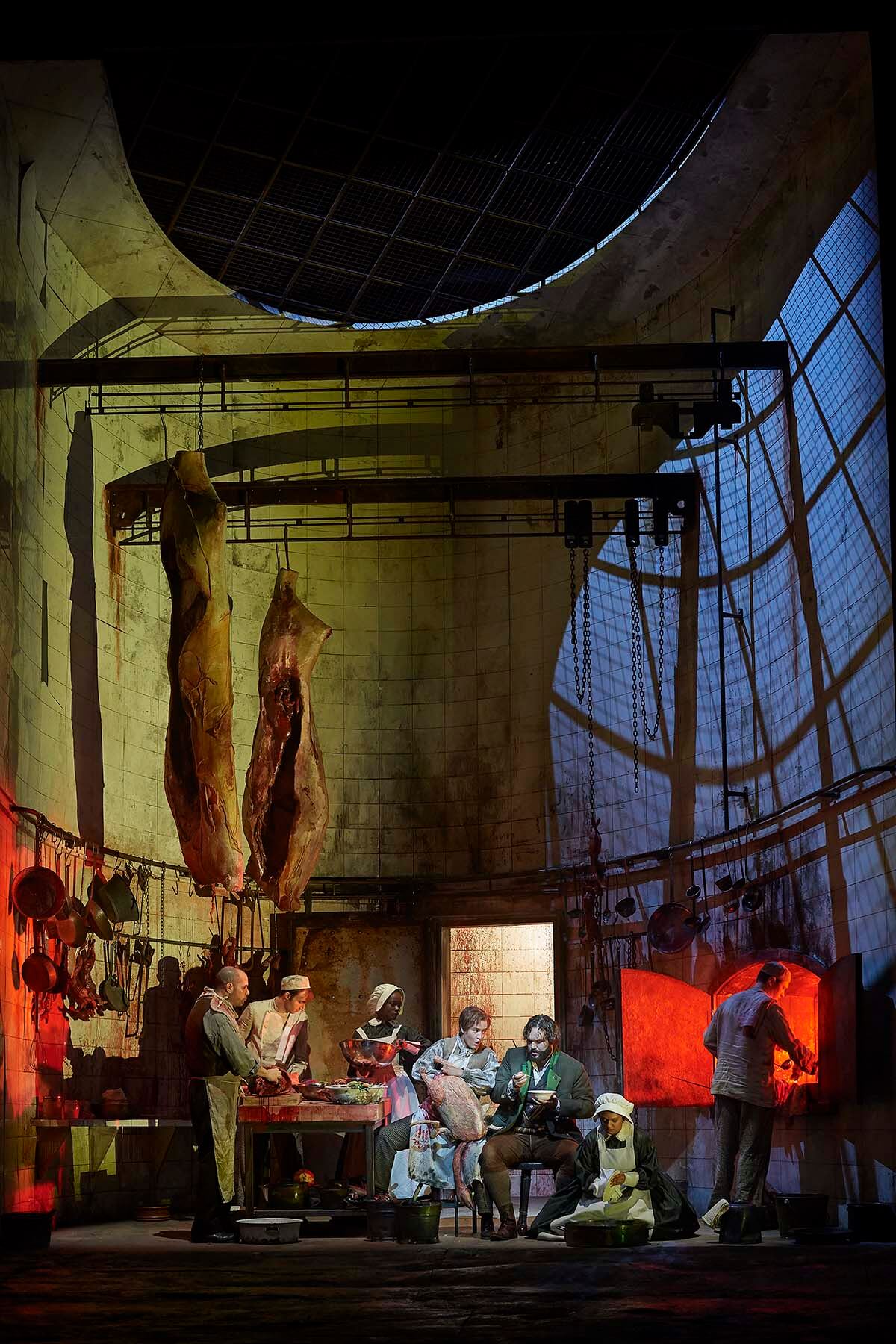

The wild frolicking of the forest creatures reflects more 21th-century sensibilities than that of a 19th-century fairy tale. The same can be said for the rather earthy characters in the Kitchen Scene. The Wood Nymphs-Vodnik scene and the Rhinemaidens-Alberich scene in Das Rheingold share similarities, but is the kindly and paternal Vodnik supposed to be a dirty old man? While on the subject of sex, is it necessary to have Ježibaba’s helpers, the three black crows, molest the Forest Nymphs?

There are also brilliant touches to be sure. I like Rusalka recognizing the animal trophies on the walls of the Great Hall, likely her friends killed by the hunters. Kudos to set designer John Macfarlane for the gorgeous setting to accompany Rusalka’s famous “Song to the Moon.” Equally magical is the starry skies of the final backdrop at the end. The Great Hall in Act Two has the requisite grandeur and provides a nice contrast to nature that dominates Acts One and Three. The downside is the excessively complicated scene changes between the acts, resulting in longer-than-usual intermissions. The evening was a rather lengthy three hours thirty-five minutes.

Dvořák was an admirer of Wagner, and it’s reflected in his music and in the dramatic structure of Rusalka. As previously mentioned, Act One Scene One recalls the opening of Das Rheingold. Act Two, with the grandeur of the Great Hall, it could have come straight out of Tannhauser or Lohengrin. The dying Prince in the final scene is evocative of Tristan und Isolde. Sitting in the audience, I was struck by the fullness of sound, with its unmistakably Wagnerian tinge.

The title character needs the vocal heft to ride the orchestra, and we have in soprano Sondra Radvanovsky the ideal interpreter. She sang an exquisite Act One “Song to the Moon,” and an equally sublime Act Three aria, a gorgeous piece if less famous. One is struck by the power of her sound. On opening night, there were moments of high fortissimos where she was unaccompanied — my ears were ringing afterwards! And her trademark high pianissimos were very much in evidence.

Rusalka is essentially through-composed, albeit conductors often provide the obligatory stoppages for applause. Kudos to COC’s Johannes Debus for having none of that, as a result, the drama flowed beautifully. Radvanovsky was well partnered by the Czech tenor Pavel Černoch as the Prince in his COC debut. Looking suitably princely with a ringing tenor to match, he had no trouble with the very difficult role that goes up to a high C. He had excellent chemistry with Radvanovsky, and their two extended duets were memorable.

Russian mezzo Elena Manistina returned to the COC as an unusually youthful Ježibaba, singing strongly and acting up a storm. Bass Stefan Kocan, also making his COC debut, was a most sympathetic Vodnik. Soprano Keri Alkema returned to the COC for her fifth role, as the Foreign Princess. The character only appears in Act Two, but Alkema seized the moment, singing generously. It also didn’t hurt looking like a million dollars, bedecked with a ton of over-the-top jewellery.

The supporting roles were all ably taken. I was particularly impressed with the three Wood Nymphs (Anna-Sophie Neher, Jamie Groote, Lauren Segal) for their athleticism as well as their fine voices. Two more first-year COC Ensemble singers — tenor Matthew Cairns sang well and commanded the stage as the Gamekeeper; and bass-baritone Vartan Gabrielian showed promise as the Hunter. Comic relief – and fine vocalism – was provided by Lauren Eberwein as the Turnspit, who spent the scene doing unspeakable things to a huge fowl, and opening night happened to fall on Canadian Thanksgiving weekend.

The COC Chorus was its usual excellent self. I’d be remiss if I don’t mention the ten dancers for their sparkling routines in Act Two. Top honours to the COC Orchestra for the torrents of sounds coming out of the pit. COC Music Director Johannes Debus fully brought out the near-Wagnerian sonorities. This is an opera that I’ve seen nearly a dozen times, including at the Met and Munich. This opening night show ranks among the best.

Six more performances to October 26.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.