Follow along as we uncover the history behind why the oboe is used to tune the orchestra.

An orchestra is a large and flexible entity. Ranging from just over a dozen (a typical small string orchestra) to over a hundred-strong (Mahler and Wagner, anyone?), it incorporates many different instruments (strings, woodwind, brass, keyboards and percussion), and may also feature vocal soloists and/or choir(s). In fact, good orchestral music thrives not only on its melodic and harmonic content, but also from the variety of timbre and colours available from the ensemble. These instrument families differ significantly from one another in their methods of sound production, and though they share a European heritage, to play together, accurate tuning from all members is an absolute must.

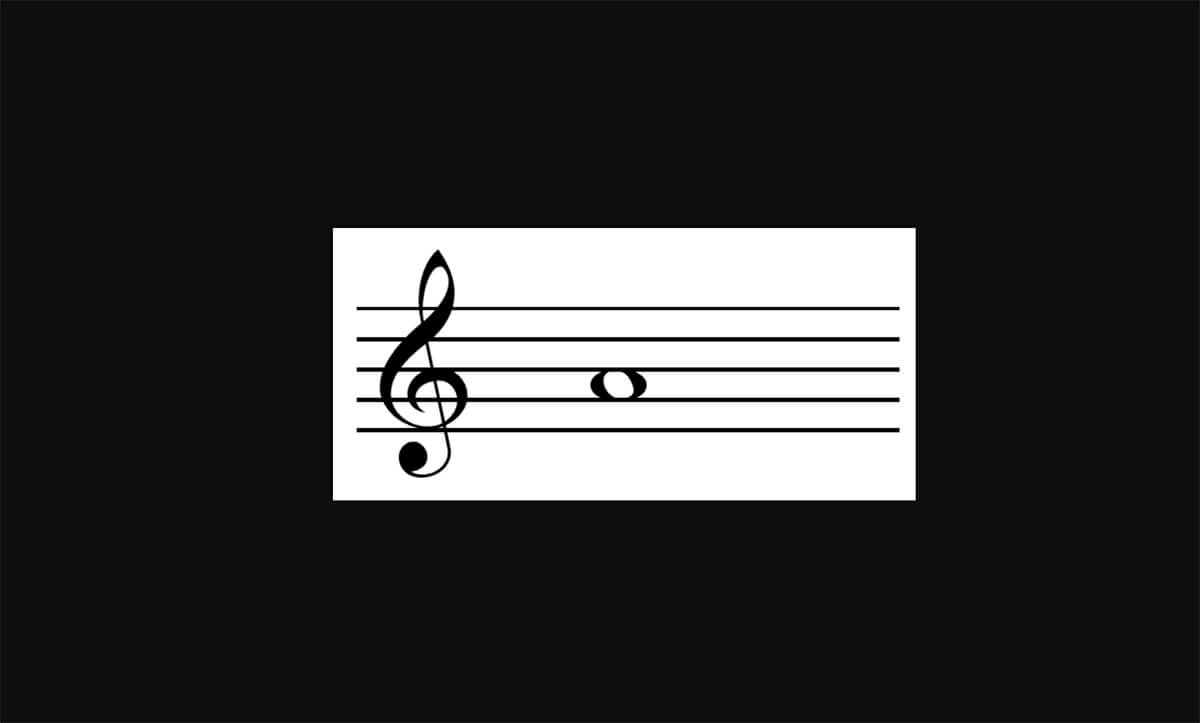

Now, you may recall how the pre-concert bustle of the orchestra comes to a halt, to let a small, yet bright note ‘A’ to emerge from the middle of the orchestra from the principal oboe. The entire ensemble tunes their instruments to this A, before a soloist/conductor walks out to start the concert (there may be exceptions, such as a piano concerto, where the concertmaster walks up to the piano to strike the middle A for orchestra’s tuning). Have you ever wondered why and how the orchestra tunes with the principal oboe’s A, and what it means?

Pitch Standard

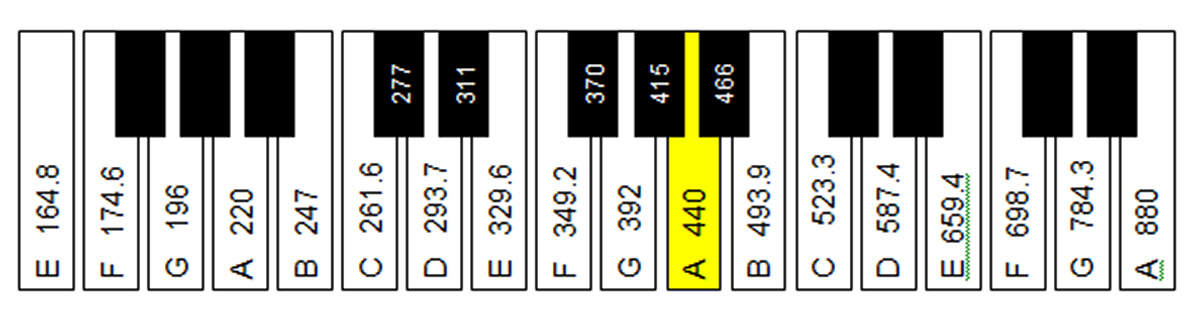

The concept of pitch standard involves a few different things: audio frequency, note-name and standard. For instance, the local tuning pitch of the principal oboe: A 440, refers to two separate concepts:

1. This note is referred to as the middle A, or A4. The middle C of the piano is the 4th C from the bottom of the keys (from the left side), hence A of that octave is referred to as A4. The lowest common note on the piano, the big growly A on the bottom, is an A0 (zero).

2. We mostly set this particular A (A4) at 440 Hz (meaning it oscillates 440 times in a second).

Let’s look at little details:

A. A 440 was set quite recently (approved in 1834 at the Stuttgart Conference by physicists, then adopted by the American Standards Association in 1936, and the International Organization for Standardization in 1955), and it still is used in most places as the standard tuning note *though the pitch is on the move, upward: it’s now common to tune to A442 (NY Phil, and most of western Europe), and many central European orchestras now tune to A443 (including the Berlin Philharmonic). In historical performance practice, their note A would be set much lower, around A 415. So, though both are called A, the historical performance A (415Hz) would typically sound a semitone lower (equivalent to A flat in today’s standard tuning).

B. when you double the frequency of a pitch, you get the distance of an octave (that’s 12 semitones). So from A4 (440 Hz) to A5, the octave above it (880Hz), you have 440Hz to spread over 12 semitones. There are multiple tuning systems on how to distribute these 12 tones, meaning each tuning system may assign a slightly different pitch (actual sound) for a single note (note from the scale). A concert piano is likely to be tuned at equal temperament, where all 12 tones of an octave have been equally divided within that 440Hz-880Hz range, but a violin may be tuned in Just, Pythagorean, or any other tuning system.

Therefore, presently, every member of the orchestra tunes to the oboe’s A (likely to be at A 440 in North America), and are expected to employ the most appropriate tuning system for the concert (eg. if you are playing in a string ensemble, you may choose, as a group, a particular tuning system, to suit the music better), and adjust your technique (eg. alternative fingerings, choice of finger placements on string instruments, embouchure adjustment) to overcome these little pitch differences to play a note in agreement.

Historically, the centre pitch has differed so much from one place to another, that the regional differences and moving pitches often drove musicians mad. When Rossini began conducting at the Paris Opéra in 1826, where they had recently dropped the tuning note by a semitone, he was very unhappy: “it is used nowhere else in the world, and it has deprived the instruments of brilliance and force.”

For certain instruments, extra parts were available and commonly used to physically alter the sound and range: “… but because in almost every province or city a different pitch for tuning instruments has been introduced and is now more or less dominant, and beside the harpsichords are tuned sometimes higher or lower due to the negligence of those who must tune them, the flute was given more joints that is, it was provided with corps de rechange*.” (Johann Joachim Quantz)

*Corps de rechange for flute was one or two (though up to set of six were sold) of the joints that can be added usually somewhere in the middle, or in Quantz’s flutes, on the longest joints. And today, you may see flutists and clarinettists adjust the length of their instruments by pushing in/pulling out the parts.

Early Days

But it wasn’t the oboe who set the centre pitch in the earlier days. Up to the late 16th century, most sacred music was vocal, so the instruments — organs mainly, were built to suit the range of the human voice (hence lower). However, when secular instruments such as violin and cornett were introduced into service, tuning became an issue, as sacred pitch differed from the opera pitch, chamber music pitch and military pitch, with heavy local variation; Composers of early 17th-18th century were commonly notating music in more than one key on a need-to basis, to overcome regional and instrumental differences.

Many travelling musicians started to look for a portable solution to this problem. Handel carried his own pitch pipe, John Shore in the early 18th century used a fork to tune his lute. The pitch pipes were like a small recorder, often fitted with a movable wooden plunger or piston, on which a scale of notes with a range of about one octave was marked. In Vienna, even piano technicians were using them for keyboard instruments, as recently as 1805. And some pipes were made to suit a few different pitches. The corista a fiato in Bologna from the 18th century, has a sliding device inside, producing three different tones: they are indicated on the wooden plunger as two Milanese pitches (A at 425 and 375), and one Neopolitan pitch (A = 411).

After Lassus began to incorporate string instruments into sacred services for the Bavarian Court in Munich around 1569, other instruments started to trickle into the church, and the limited flexibility of woodwind instruments often determined the pitch setting: sackbuts were employed in sacred services in Emden in 1570s, and Catharinenkirch in Hamberg was regularly using cornetts by 1590s. The best cornetts were made in Venice, and they were often sold in sets with a common pitch system; and though much of the sacred music was made to match the human vocal range (hence a bit lower), cornetts at a lower pitch were very difficult to master, as the tone-holes had to be placed wider in a longer body, requiring incredible finger stretches, which made it impossible for mere mortals to play. Instrument makers had no choice but to make cornetts in a higher pitch. Before long, all instruments, including the organ (!) were tuned around the cornetts:

“[the organs] of Venice are among the highest used in that state, and must be tuned to the pitch of cornetts. Chamber organs, though, at Venice, Padua, Vicenza, and other cities, are a tone lower, (corresponding to) the human voice, which is called corristi. This difference in pitch is used to accommodate voices and instruments, since organs that are high work well with lower voices and violins, which are for this reason more spirited.” (Antonio Barcotto, from his manuscript Regola e breve raccord, 1652)

This tuning pitch, Cornettenthon, remained constant from 16th through 18th century, and was used widely in Italy, Germany and Austria.

France

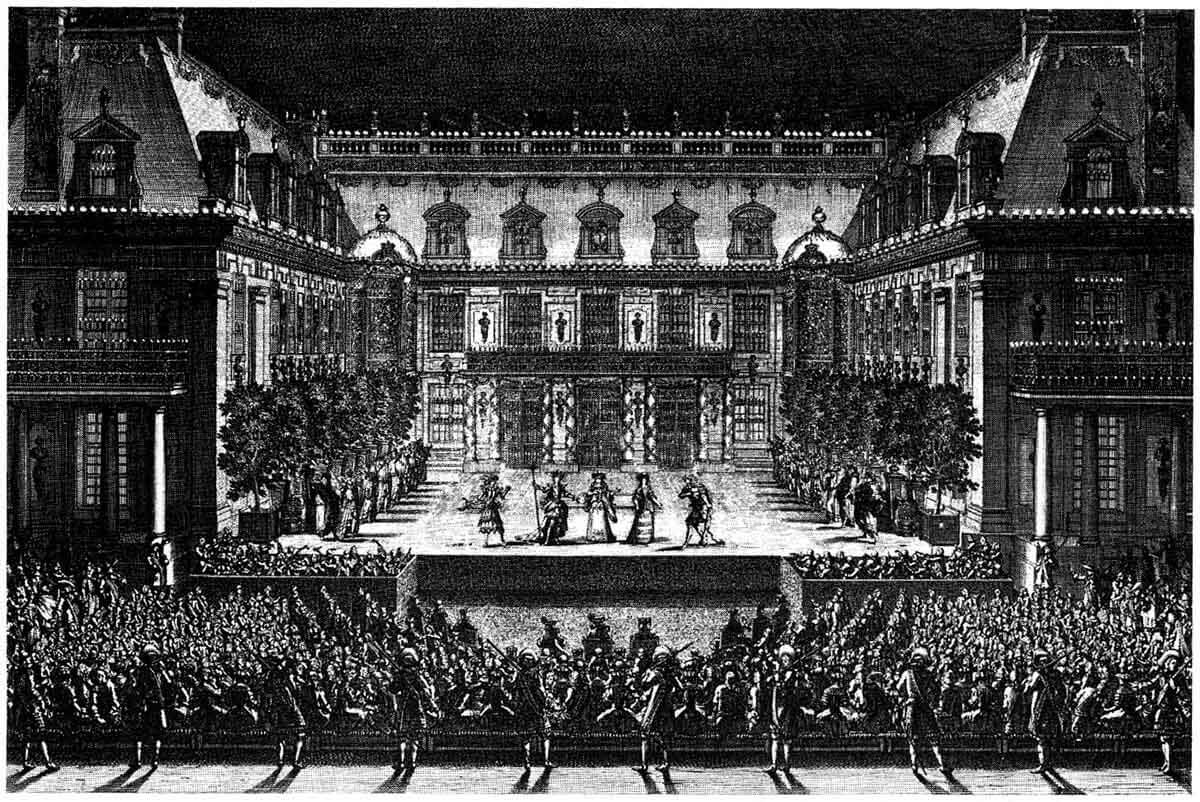

Meanwhile, in France, the royal court had two main musical ensembles: Les Vingt-quatre Violons du Roi, the famous five-part string orchestra, and the Grande Écurie, a wind instrument ensemble; these two, along with the splendid Opéra de Paris orchestra, and smaller specialist subgroups, such as the Douze grands hautbois, played for the court. When the ambitious Lully came to the French court, he began to integrate wind instruments into the string orchestra. Previously, the winds at the court had almost always performed as a self-contained ensemble, primarily for royal dinners, outdoor events and ballet de cour, and it was not until Lully took over the Opéra orchestra (1672-1687), that he began experimenting with merging the two instrument families. Alceste (1674) at the Opéra is the first case where Lully truly combined woodwinds, in this case, oboes and strings into a single band. Soon, all of Europe was dying to have a piece of Louis XIV’s grandeur in their backyard. Fortunately for them, Lully’s heavy-handed monopoly and expulsion of Protestants in 1685 drove many French musicians out of France, and as a consequence, French strings and woodwinds, set in lower pitch, were adopted all over the rest of the Europe.

It is also worth noting that by the time Lully came to France in 1652, cornetts and sackbuts had disappeared from secular music, and the hautbois, still constructed from a single piece of wood (like the shawm), with just a few keys and a broad reed that the player placed fully inside the mouth, had progressed to become much closer to a baroque oboe, and near the time of Lully’s death (well, a year after his death in 1688), the first baroque oboe prototype appeared, with three joints and reeds on the players’ lips. Could it be that all three parties- Lully, the Opéra de Paris orchestra and its instrument suppliers, grew together in their shared experiment in expanding the world of woodwinds? Probably.

Europe

In Europe’s earlier days, things developed locally, adding much variety and complexity, but along with the confluence of commerce, the military, religion and developments in transport, certain entities rose to the top. The next big thing after Lully was the famous Mannheim Kapelle’s Orchestra: created by music-loving electors, Carl Phillip and his nephew Carl Theodor, the Mannheim orchestra, in its short life (1720-1778), helped to form the basic structure of the classical orchestra, and by its last year, 1778, it employed 2 organists, 35 strings, a large wind section (4 flutes, 3 oboes, 3 clarinets, 4 bassoons and 6 horns), and 13 trumpets and 2 drummers. In 1778, the orchestra left Mannheim, as Carl Theodor inherited the Electorship of Bavaria, and moved to Munich. The Mannheim orchestra contributed immensely to symphonic music, making big impressions on the first Viennese School composers — Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, in its experimentation and growth in balance, virtuosity and dynamic range.

The Expanding Orchestra

The first Viennese composers extended their orchestral development from the Mannheim Orchestra. Beethoven, with his nine symphonies, completes the first milestone of the modern symphony, musically and logistically. Though there are earlier examples, it is Beethoven’s 5th that made a lasting impression on the general public, especially in its inclusion of piccolo and trombones. Many even think that this is the symphony that elevated the piccolo to its modern role as a permanent member of the orchestra. And from Beethoven on, the rest is history: additional symphonic expansion continued, especially with Strauss and Mahler, and to this date, the orchestra as an ensemble is still expanding and experimenting.

But funnily (or frustratingly), not much definitive explanation has been found as to WHY the modern orchestra tunes to the first oboe. In the early 18th century, the common tuning practice for an orchestra involved preluding: Martin Heinrich Fuhrmann in his 1706 publication, Musicalischer-Trichter, explains that in a church, the organ should improvise, and the instrumentalists to play along in the same key, and tune during this prelude. But later musicians, including Quantz, worried that playing and tuning simultaneously would just put the instrument out of tune, and by the mid-18th-century, there were a few different thoughts on tuning protocol:

1. It is better for music to start from silence:

“… not by tuning, rustling, and fiddling around.” (Friedrich Rochlitz, 1799),

“… since well-bred persons have a natural aversion to noise, it is to be expected that they will eschew preluding of their own accord.” (Sartori, the violinist-director at the Darmstadt Hofkapelle, ca. 1792).

2. The ensemble should tune in a separate room where it won’t be heard by the audience altogether:

Andras Dauscher claims that Opéra de Paris orchestra tunes in a green room, and that German orchestras should do the same in his publication, Kleines Handbuch der Musiklehre und vorzüglich der querflöte (Ulm, 1801)

3. That performers should not tune during the performance:

“…Older players habitually begin without tuning, then tune up during vocal recitatives”. It sounds, he says, “like the buzzing of a wasp’s nest, an incessant zun, zun, zun,of violins and basses, who keep on tuning all the way to the final chorus without ever being in tune.” (Francesco Maria Verancini, c. 1760)

Tuning To The Concertmaster

It seems that well into the late 18th century, many orchestras tuned to the concertmaster:

“… So as to miss no opportunity to uphold good order and to create good intonation, I will tune my violin to a tuning fork. I will then proceed from one player to the next, checking whether his A string agrees with mine. After this, the string players, all at the same time, should tune their remaining strings as quickly as possible, while the wind instruments play the various notes of the D major chord. As soon as I give a sign, tuning is over, and everyone should remain quietly in his place.” (Sartori)

This particular tuning method was favoured by both Quantz and Mozart, though some thought it was demeaning:

“if a violinist can’t tune his open strings by himself, how can he finger the notes in tune?” (Heinrich Christoph Koch, 1802)

Other options included taking the pitch from the harpsichord or organ, (but the difference in temperaments: strings tuning in pure fifths, and keyboards tuning in equal temperaments, proved to be problematic) or from one of the winds, as the variance in temperature and humidity impacted wind pitches wildly: but which one? Many instruments were considered for this role, including oboe, flute, horn, and trumpet.

The narrow wiggle room for woodwind tuning led orchestras to buy all their wind instruments from a single maker (as they would be consistent and be in tune within the set), and often, travelling players had to result in transposition. When Ignazio Rion, a virtuoso oboist travelled from Venice to Rome in 1705, his instrument, having been made in Venice, was a whole step higher than the Romans, and Handel had to notate Rion’s oboe part a whole step lower to match the ensemble.

For a brief reference: the present scholastic research postulates that woodwinds in 18th-19th century surrounded the A 440 as we know it:

| Hz | Country |

| 392 | France, Germany |

| 403 | France, England, Holland, Belgium |

| 413 | Italy, Germany |

| 440 | Italy |

| 464 | France, Germany |

But looking at the wild range for the tuning A, even from the narrow range of 1920-1943, the A still is on the move:

| Year | A set at: (Hz) | Ensemble |

| 1920 | 428 | Berlin Philharmonic |

| 1924 | 435 | Berlin Philharmonic |

| 1927 | 448 | Berlin Staatsoper |

| 1928 | 444 | Berlin, Staatskapelle |

| 1932 | 440 | Berlin Philharmonic |

| 1935 | 445 | Berlin Philharmonic |

| 1940 | 450 | Bayerisches Staatsorchestra |

| 1943 | 450 | Städtisches Orchestra, Berlin |

Ouch.

But how did oboe became the holder of the A?

There are a few speculations, but none outstanding.

1. The oboe is particularly limited in its means of adjustment- the only pitch adjustment comes from moving the reed slightly in or out. String instruments have pegs to adjust tensions on strings, and the Brass has movable valves. Clarinets can often adjust the length of their barrel; so, the orchestra adjusts to the oboe (the bassoon is also a double-reed instrument, but as it sits lower, and harder to tune to it). However, different reeds can shift the centre pitch, so the oboe is actually quite versatile, should the player have other reeds available. In addition, the players themselves can physically adjust, and they do have alternative fingerings available for intonation.

2. The oboe, with its rich harmonics in the upper range, has a timbre than can project above the orchestra: so why not tune to the harp or even glockenspiel? The glockenspiel, being made of metal, is one of the most constant and audible of instruments (like the older tuning fork).

3. Tradition: the oboe was incorporated to the orchestra quite early. Most symphonic pieces include an oboe or two. And their seating location (right in the middle), makes them easy to hear for the whole orchestra.

Final thoughts

As discussed in the saxophone and orchestra, ‘tradition’ may be the best answer. Orchestras are notoriously traditional, and sometimes, there are no reasons to fix what’s not broken — an oboe giving the A440 (or higher, as it creeps up steadily, especially in Europe), has been working just fine for a few centuries. In fact, as many musicians tune with portable electronic tuners well before the oboe note, it is debatable whether such a ritual holds any practical value. However, as the keeper of tradition, there is no danger of the orchestral abandoning its tuning rituals, and when you hear that cacophony of sounds flowering from the oboe’s A, sit back and get excited — a concert is about to start!

LUDWIG VAN TORONTO

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- CRITIC’S PICKS | Classical Music Events You Absolutely Need To See This Week: April 22 – April 28 - April 22, 2024

- CRITIC’S PICKS | Classical Music Events You Absolutely Need To See This Week: April 15 – April 21 - April 15, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Laurie Anderson Entrances A Sold-Out Koerner Hall With A Journey Down The Rabbit Hole - April 8, 2024