Pfitzner & Braunfels: Piano Concertos (Hyperion)

★★☆☆☆ / ★★★★☆

🎧 Apple Music | Amazon | Hyperion

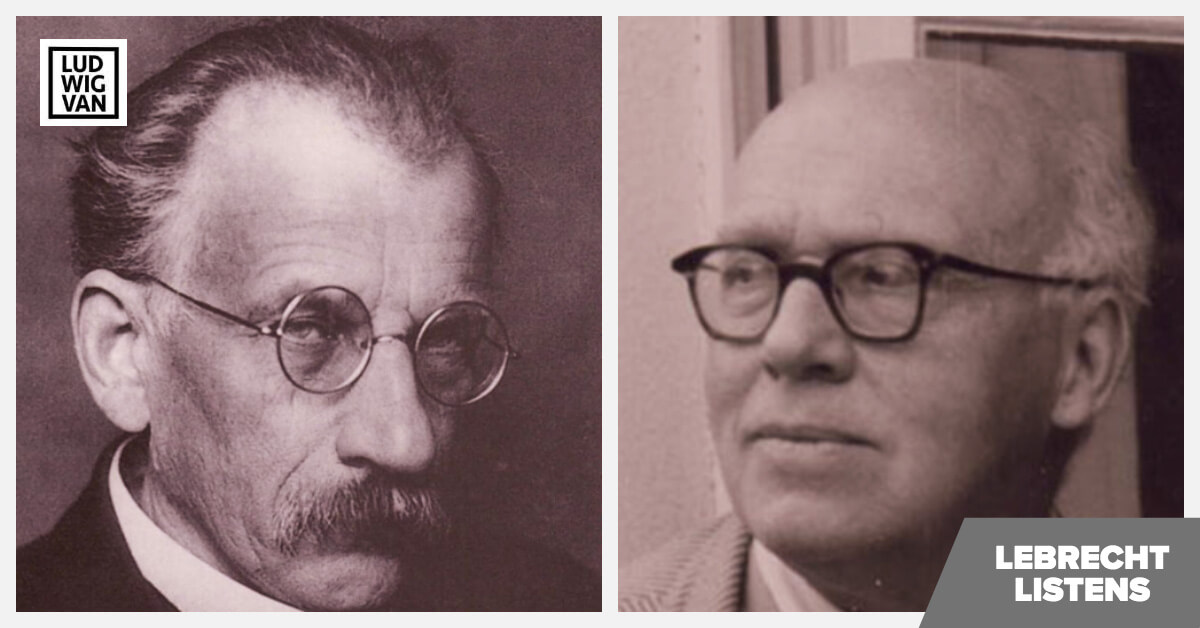

The anniversary year of Hans Pfitzner (1869-1949) is marked by the re-emergence of a piano concerto that he wrote at the height of his fame. Pfitzner, acclaimed for his 1917 opera Palestrina, delivered the concerto in 1923, with Walter Gieseking as soloist. If Palestrina echoes Wagner’s Meistersinger, the concerto nods repeatedly in the direction of Brahms’s B-flat — and the nodding is done mostly by the listener.

Pfitzner’s fallen reputation is sometimes ascribed to his gruesome flirtation with the Nazis but this concerto suggests something more organically at fault. Each of four movements is introduced by a promising idea, which promptly gets lost in a mound of bombastic waffle. I have seldom heard a piece that is so utterly all-over-the-place, so directionless and devoid of purpose that the eye strays to the wristwatch (only 40 more minutes to go) and the ear prays for an armistice.

I toyed with the possibility that the soloist Markus Becker and conductor Constantin Trinks might have taken wrong tempi or, worse, taken Pfitzner at his own inflated estimation, but the second concerto on this Hyperion release shows them to be skilled and sensitive interpreters of music by a composer of decidedly superior character.

Walter Braunfels (1882-1954), who lived quietly in Cologne, had his music banned in the Third Reich on racial (half-Jewish) and religious (devout Catholic) grounds. A ‘piece for orchestra with piano obbligato’ that he wrote for the drawer in 1933-34 resurfaced only recently in the family archives, in 2017. Late-romantic, with the odd nod towards Hindemith, it represents an inner meditation of a lone soloist in a mass society gone mad. There is tension in the dialogue and tautness in the structure, with five contrasting movements and a surprisingly upbeat A-major ending. Bruckner and Mahler are primary influences, but Braunfels is his own master and he knows how to sustain attention. This timely discovery should really be taken up by our more adventurous symphony orchestras.

To read more from Norman Lebrecht, follow him on Slippedisc.com.

LUDWIG VAN TORONTO

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Jordan Bak’s Cantabile For Viola Reveals The Neglected Instrument’s Beauty - April 12, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS |David Robert Coleman & The Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Reveal The Charms Of Walter Kaufmann - April 5, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Recordings Of Ysaÿe, Brahms & Busoni Show Not All Violin Concertos Were Created Equal - March 28, 2024