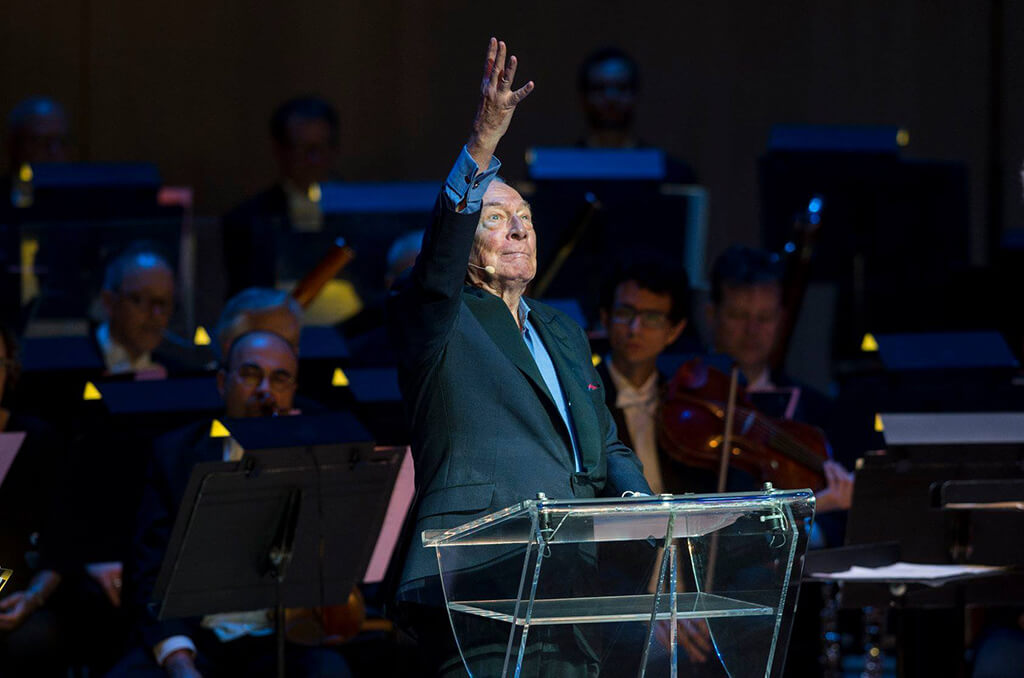

Toronto Symphony Orchestra with Christopher Plummer (narrator), Peter Oundjian (conductor) at Roy Thomson Hall, Tuesday.

Peter Oundjian came to the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in 2004 with an open mind as well as a baton. Tuesday in Roy Thomson Hall he shared the spotlight in his penultimate program as music director with a fellow Canadian, Christopher Plummer, who also happens to be his neighbour in Connecticut.

“Surrendered the spotlight” might be more accurate: the one-night-only presentation was called Christopher Plummer’s Symphonic Shakespeare. Oundjian stood somewhat to the right on the stage of Roy Thomson Hall to give the great actor a central rostrum and space to move. Words and music in succession were given more or less equal measure, but there could be no doubt as to the identity of the star of the show.

Trained as a pianist in his youth, Plummer remains a musician in his 89th year. The voice is still full and melodious, the sense of rhythm unerring. To hear vowels extended so seductively is to realize how much of Shakespeare’s achievement was musical. Perhaps his microphone gave an edge to sibilants, but these were readings that might have entertained an auditor with no knowledge of English.

Of course, the recitation was based on sense and as well as sound. The range of characterization was extraordinary. Plummer was able to give convincing voice to both old Falstaff and young Henry V in the latter’s repudiation of his former drinking pal in Henry IV Part 2. Remarkably, Plummer played Juliet as well as Romeo. “Why not?” he asked the crowd, perhaps alluding to the wave of gender-switching overtaking the theatrical world.

There were passages from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Cymbeline, Much Ado About Nothing, The Taming of the Shrew and The Tempest; many recited from memory. Most impressive was a dramatic (rather than generically “poetic”) performance of Sonnet 130 (“My mistress’s eyes are nothing like the sun”). Here and elsewhere, words were enhanced by the subtle movements of a master.

Might we have had more episodes from tragedies? I suppose the understandable objective was to keep things upbeat. In any case, the concluding minutes were deeply moving. We had words of resignation from Prospero and, as a final cadence, five less familiar lines from Much Ado, ending: “Thanks to you all, and leave us. Fare you well.”

One might wonder what music was found to support Much Ado. Berlioz’s boisterous Overture to Béatrice et Bénédict is rare enough. The “Garden Scene” by Erich Wolfgang Korngold is even rarer. This gentle number for piano and strings was drawn from incidental music the 20-year-old Viennese composer wrote for the Burgtheater in 1918.

There were many other novelties on the program, for which the Ottawa cellist and impresario Julian Armour was given partial credit in a footnote. The opener was Wagner’s Overture to Das Liebesverbot (i.e. Measure for Measure). We heard traces of Lohengrin in the brass fanfares, but otherwise, this jaunty item suggested a budding composer of operetta.

Other off-brand selections included Debussy’s King Lear Fanfare (in which we could hear a touch of Ondine) and some turbulent excerpts from Tchaikovsky’s The Tempest Fantasy-Overture. Oundjian and TSO have an aptitude for this composer. A brief but lushly romantic Adagio from Healey Willan’s music for Cymbeline suggested that this great Canadian’s non-liturgical music is due for reassessment.

There were, not surprisingly, extended sequences dedicated to Mendelssohn’s incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, William Walton’s film score for Henry V and Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet. In all cases, but especially Prokofiev, the music was given new life by the literary context. TSO strings were nimble in Mendelssohn’s Scherzo and resonant in “Romeo at Juliet’s Grave.” Associate principal cello Emmanuelle Beaulieu-Bergeron provided handsome solos in the Korngold and Nino Rota’s film music for The Taming of the Shrew.

All this was made a continuous fabric by impeccable timing. Typically Plummer entered on a final chord, securing our attention without losing a beat. Even his strolling from chair to lectern had an element of dramatic veracity.

Many in the crowd were doubtless expecting repartee, Oundjian being no slouch with the microphone. There was some gestural onstage chemistry, but Plummer did all the talking. Possibly the conductor reasoned that conversation would compromise the integrity of what was indeed a very classy night. It is tempting to recommend “symphonic Shakespeare” as a formula for future presentations, but there is only one Christopher Plummer.

- SCRUTINY | Moussa Concerto Sounds Strong In Toronto Symphony Orchestra Premiere, Paired With Playful Don Quixote - April 4, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Esprit Orchestra At Koerner Hall: Ligeti 2, Richter No Score - April 1, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Sibelius & New Cello Concerto By Detlev Glanert Offers A Mixed Bag From The TSO - March 28, 2024