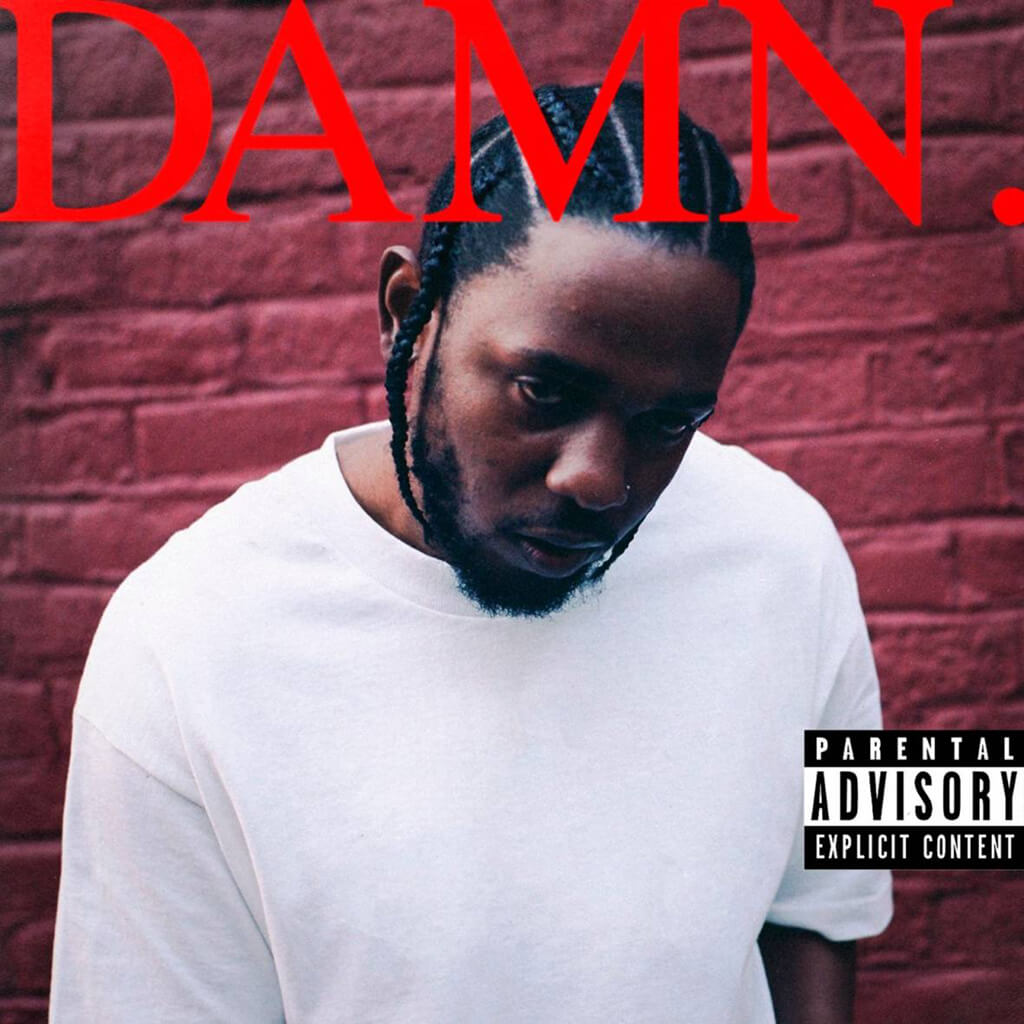

Among the many “breakthroughs” that have followed in the wake of Kendrick Lamar’s 2018 Pulitzer Prize for the album Damn is the fact that a hip-hop artist is now being discussed in classical music circles. “What are we to make of this development?”, various classical-music commentators, practitioners and enthusiasts are asking. Is this a good thing? Or a bad thing? Or what?

I’ve noticed that some classical types have been careful to sound respectful and inclusive when discussing this issue. Perhaps fearful of being labelled “elitist,” or hoping that just a little bit of hip-hop’s coolness might rub off on them, they praise Damn for its musical craft, sophistication and cultural authenticity, and say supportive things about Lamar’s prize-win. (See here, here or here.)

On the other hand, an outraged Norman Lebrecht called the decision, “an almighty kick in the teeth of contemporary composition.” And, predictably, the decision has also coaxed some downright racist reactions out of the woodwork. I suspect that some of these outraged folks, bravely defending good taste and high standards, didn’t even know there was a Pulitzer Prize for music until Lamar won it.

As a classical guy myself (living in Toronto, Canada, by the way), I must admit that I didn’t know much about Lamar until a couple of days ago. Since then, I’ve listened to some of his music, and I can only agree with the more “progressive” voices in the classical music world, where Lamar’s musical craft and sophistication are concerned. I’m no fan, yet I can’t deny that Lamar is very good at what he does.

But a Pulitzer? Frankly, this alarms me — and I’ll tell you why. And then I’ll offer some free advice.

For some time now, classical music’s place in North America has been shrinking, encroached upon by other genres. Even though classical music’s – and especially contemporary classical music’s – cultural footprint is already small, there is pressure on us to “share” what’s left of our turf or be denounced as disdainful, highbrow snobs. This kind of sharing might be a good thing if it were a two-way street, but often it isn’t. A decade ago, when the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Radio 2 network drastically slashed its classical programming to make room for a variety of popular musics, did pop radio stations reciprocate by playing more (or, rather, any) classical music? Of course not.

And the problem is partly our own fault. For too long, many musical institutions that have long existed to support and present classical music have been content to use the word “music” without specifying that they’re talking about classical music. My favourite example of this is a local concert series called simply “Music Toronto,” which presents classical chamber music only. Moreover, it’s also a kind of Achilles heel for the classical music world, placing our music and our institutions in a vulnerable position.

For example, consider the Pulitzer, a music prize whose guidelines state that it should be awarded “for distinguished musical composition by an American.” Even though the prize has almost always been awarded to a classical composer (with the exception of a few jazz artists) there has never been an official statement of this policy – it was an unwritten tradition. For decades, the Pulitzer for music was pretty much a genre-specific kind of award, just as the Tony Awards or the Academy of Country Music Awards are genre-specific. The only difference was that the Pulitzer was implicitly genre-specific, and the latter two examples above are explicitly genre-specific.

Yet that difference is significant. It was only a matter of time before someone rhetorically asked, “Hey, wait a minute, if the Pulitzer is for ‘distinguished musical composition by an American,’ why shouldn’t hip-hop be considered?” And the Rhetorical Asker was right, and the Pulitzer Prize for Music must now be shared among (presumably) all genres of American-made music. And the small and marginalized contemporary classical music world just got a little smaller and more marginal.

So what’s to be done in the face of this cultural erosion? For the Pulitzers, there’s probably no going back: the move to broader inclusion has already been made. Only time will tell if Lamar’s prize is a gesture of tokenism, or if the Pulitzers will largely embrace popular musics, and America’s classical composers will find themselves shut out of a prestigious award that used to “belong” to classical music.

But to other institutions of classical music, I propose this: We can better support our cherished art form by clearly expressing a commitment to classical music, per se. Orchestras, opera companies, conservatories and other classical music institutions should take a good look at their constitutions, mission statements, letters of incorporation, etc. and ensure that classical music is explicitly named as the kind of music the organization primarily supports.

The clarification I’m proposing need not be presented as an act of hostility against non-classical musics. To say you support one kind of music need not mean that you are opposed to another.

Rather, such clarifications would simply be a useful and well-timed invocation of the old adage that good fences make good neighbours.

Finally, I’d like to congratulate Mr. Lamar on his prize. Love and peace to all.

A version of this article originally appeared on Colin Eatocks blog, Eatock Daily.

- ISSUES | The Pulitzer, And What Classical Music Needs To Do - April 19, 2018

- SCRUTINY | Aisslinn Nosky and Tafelmusik Present a Cheeky “Baroque Misbehaving” - April 25, 2015

- CONCERT REVIEW | The Unmistakable Elliot Madore - March 27, 2015