It has taken a long thirty-eight years for Abduction from the Seraglio to return to the Canadian Opera Company. The Mozart masterpiece was last staged by the COC in December 1980. According to the most recent statistics from the last five opera seasons worldwide, Abduction ranks popular at 27 out of a total of 2,662 operatic works performed. Impressively, it’s the sixth most performed opera in Austria, the birth country of Mozart. It begs the question why has it taken so long to return to the COC.

Certainly not because of the quality of its music, as the scintillating score is considered one of Mozart’s gems. Its five principal roles, while vocally challenging, are composed gratefully for the voice, and there are plenty of fine Mozartians today to do it justice. The real answer lies in the story itself. A comedy that centres on two young European women abducted and forced into sexual slavery in the Middle East is hardly comedy material by 21st-century standards, or any standard for that matter. This is not meant as a condemnation of Mozart or his librettist Christoph Friedrich Bretzner. The creators’ respective worldviews were simply shaped by their time, and the Mitteleuropa culture where they lived.

Historically, opera as a western art form was understandably Eurocentric, underscored by a simplistic worldview towards non-European cultures. There are abundant examples in the repertoire, L’Italiana in Algeri, Madama Butterfly and Turandot come readily to mind. The portrayals of the characters are often stereotypes, not based on first-hand knowledge but more a function of their fertile imagination. There are many more examples, many have fallen into obscurity, such as Leoni’s L’Oracolo. Others like The Mikado and Das Land des Lächelns pass muster because they are seen as harmless and quaint period pieces for pure entertainment purposes.

A fair question to ask is, given the values of society today are very different from those in the mid-18th-century, how should these operas be performed in our time? Should we treat these as museum pieces, performed unaltered, or would some re-imagining be necessary given our 21st-century sensibilities? Abduction is a particularly problematic piece for this very reason. Wajdi Mouawad, director of the COC production, has taken the view that a re-thinking is in order. Mouawad, I’m told a Lebanese Christian, writes in his Director’s Notes: “I’ve been shaped equally by Eastern and Western culture…and incapable of condemning one civilization at the expense of the other.”

To this end, Mouawad has reframed the story to underscore the capability and power of goodness, compassion, forgiveness, and love, in people from all cultures. He has added a substantial amount of dialogue, and created an extended opening scene, which takes place after the characters (Konstanze, Blondchen, Belmonte and Pedrillo) have returned home, having been granted clemency by Pasha Selim. At the Homecoming celebration, Konstanze expresses her dismay at the overt Muslim-bashing, in the form of a crude “Hit the Turk” game. Soon it becomes apparent that in the intervening two years, Konstanze has gained in her understanding of a different culture. Belmonte and Konstanze then proceed to tell each other their experiences the last two years.

In the Mouawad Abduction, the storytelling is structured as a flashback. The experiences of the two women, Konstanze and Blondchen, in captivity has given them insight and understanding into the inherent goodness of people. This re-imagined take by the director has the effect of giving the two characters, particularly Konstanze, transformative power and personal growth not in the original Mozart. In essence, this Abduction is not the rather frivolous comic opera but an opera seria, one with a powerful message. Konstanze’s transformation somehow reminds me of the Kaiserin’s in Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten. Like her, Konstanze has acquired an understanding of what human compassion and love truly is. In Mouawad’s vision, the two women are the most enlightened, the most empowered in the story. His concept, while far from perfect, has a special resonance in today’s society.

How much of this Abduction is Mozart’s and how much is Mouawad’s? There is no simple answer. While no music is added, whole scenes are created, such as the opening. The biggest difference is the addition of a huge amount of German dialogue, written by the director and inserted throughout the opera. I don’t have a copy to compare it to Mozart’s original singspiel, but I have a feeling it’s around two-thirds new. I also have a feeling that in addition to the new material, some of Bretzner/Mozart’s original spoken text has been altered. Some changes are very obvious, such as the addition of Muslim prayer service that opens Part 2, a very striking – even jarring – moment. Incidentally, the off-stage voice of the sung part of the prayer service belongs to the Swiss tenor Mauro Peter (Belmonte). Given the added material and all cuts restored, it makes for a long evening of three and a half hours including a single intermission.

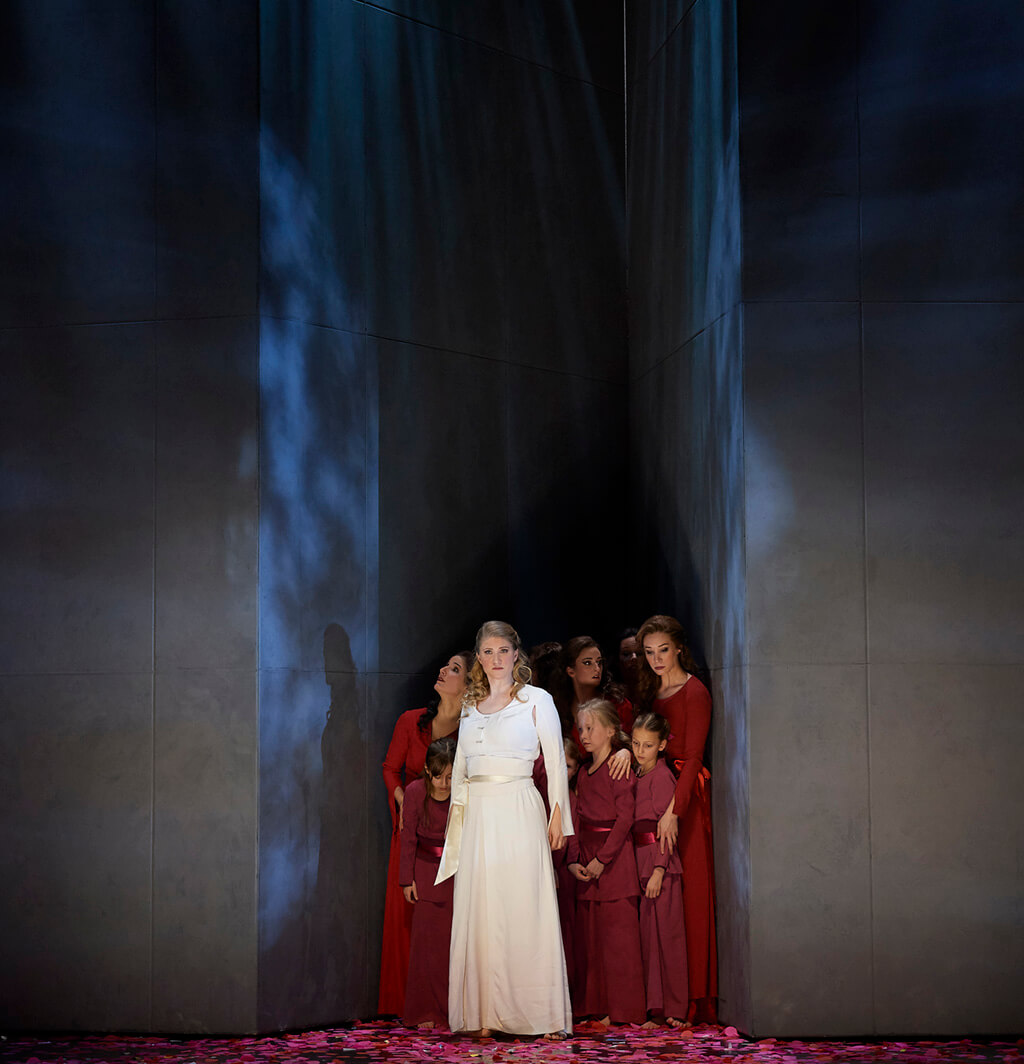

The set is abstract, a few obligatory chandeliers and a couple of Louis XIV chairs in the opening scene notwithstanding. It’s completely devoid of Islamic motifs, likely intentional. Two enormous and movable blocks on either side of a central sphere, which at the end of the opera rotates to reveal the seraglio where the women are kept. The costumes are traditional. A quirky touch is the costuming for the chorus, making them more like inmates from Auschwitz than the Ottoman Empire! Not the most interesting show visually, but given the new directorial take, I can understand the motivation to strip it of traditional Islamic symbolism. A more serious issue is Mouawad’s decision to forgo much of the comedy in favour of weightier subject matter. A couple of audience members later said to me they weren’t even sure if they were supposed to laugh! One light moment is the Osmin-Pedrillo scene involving the latter tempting Osmin to drink wine, which probably makes for uncomfortable viewing by those of Muslim faith.

In the final analysis, I have come to accept the notion that Abduction as a sort of 18th-century slapstick no longer works in today’s world, where different societies and cultures are more interconnected than ever. Some Abductions have kept it farcical, a sort of a three-hour cartoon. But I feel Mouawad’s vision is a thoughtful, earnest, and well-considered attempt at updating. There are those who feel Mozart’s work doesn’t need renovation – redemption, forgiveness, the power of goodness, and the triumph of truth versus falsehood are all laid out in his greatest works – Tito, Idomeneo, Zauberflöte, etc. We can only find the answer to this debate within ourselves. For me, Mouawad’s vision is a valiant effort, and his heart is in the right place, as they say. As is often the case of trying to retrofit something that’s two hundred fifty years old, you gain some, and you lose some. The biggest loss maybe the lightness of the original, but that’s par for the course. Given the weighty subject matter, it has had a rather ponderous and didactic feel, especially the end. It’s a price worth paying.

The ensemble cast sang beautifully on opening night. This is Canadian soprano and COC Artist-in-Residence Jane Archibald’s second role this season. Her silvery-toned lyric-coloratura has excellent agility and sufficient power for Konstanze, perfect for the showstopper “Martern aller arten.” Her high D’s were brilliant. She’s also a sympathetic heroine, singing an affecting “Traurigkeit.” It helps that she is partnered by the excellent Swiss tenor Mauro Peter in his North American debut as Belmonte. He sang with beautiful, aristocratic, warm yet virile tone throughout, including a wonderful “Ich baue ganz,” which is often cut in performance. With all the cuts opened, Belmonte is a huge sing, but you likely won’t find a better tenor to tackle this music.

The second couple was equally well cast. Soprano Claire de Sévigné (Blondchen) offered her customary crystalline tone, her stratospheric top clear as a bell. She is about the same height as Archibald, so the two look more like sisters than mistress and maid. Kudos to Owen McCausland (Pedrillo) for singing with almost heroic tone, in a role that’s often under-sung. As the one soloist with the least European experience, he offered very impressive German diction in his huge amount of dialogue, likely due to the good work of German diction coach Adi Braun. In fact, with so much spoken dialogue, it makes me wonder if some discreet amplification was used to help ease the strain on the singers. I am told that no amplification is used, which underscores the fabulous acoustics of the FSC. Given the opera seria treatment, you’d think the Osmin character is less interesting, but Croatian bass Goran Jurić shone both vocally and dramatically in his scenes — bravo! Finally, Israeli actor Raphael Weinstock was an unusually sympathetic Pasha Selim, with all the gravitas that one could ask for.

The COC chorus did its customary great work, despite the ungrateful makeup and costume job. The COC Orchestra played wonderfully well with Johannes Debus at the helm. He was not afraid to give space to the drama with frequent pauses. The orchestra, slightly reduced per Mozart’s requirements, played flawlessly. This production, first seen in Opera de Lyon in 2016, likely will generate divided opinions. There were two boo-birds a couple of rows behind me, rather unusual given how undemonstrative Canadian opera audiences are. The applause at the end, while warm, was not vociferous. It’s undeniable that Canadian opera audiences are a conservative bunch, but much less vocal than the Met audiences, where they are dismissive of Regieoper, using an uncomplimentary term which I won’t repeat here. For me, there are bad Regieoper and good Regieoper. As long as it makes sense and is respectful of the original, I am open to new interpretations. This Abduction is one director-driven production that is thoughtful and well-considered, and it deserves to be seen.

Abduction from the Seraglio, seven performances, Feb. 7 to 24, Four Seasons Centre. www.coc.ca

LUDWIG VAN TORONTO

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and reviews before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

![]()

- SCRUTINY | Opera Atelier’s All Is Love Makes Triumphal Return - April 15, 2024

- SCRUTINY | From The Heart: Ema Nikolovska And Charles Richard-Hamelin Offer Unique Program At Koerner Hall - March 26, 2024

- SCRUTINY | The Glenn Gould School Spring Opera Presents A Superb Dialogues Des Carmélites - March 22, 2024