A guided journey with Christos Hatzis

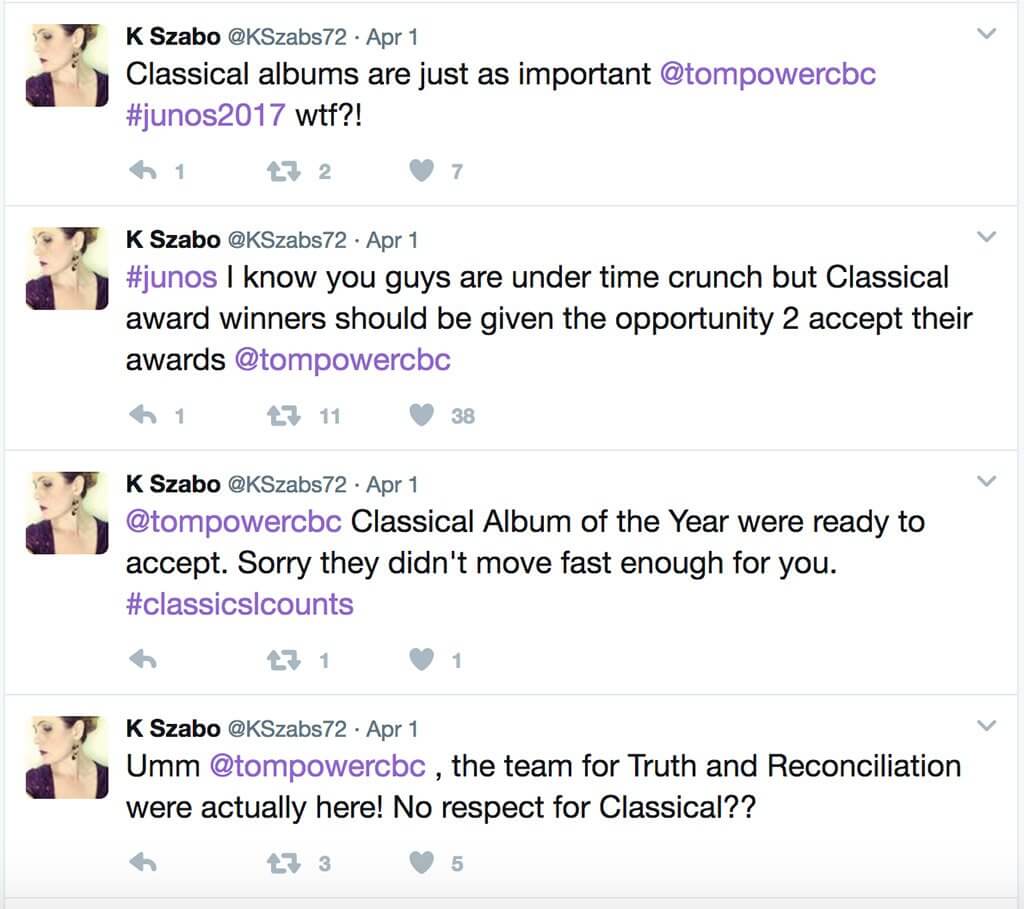

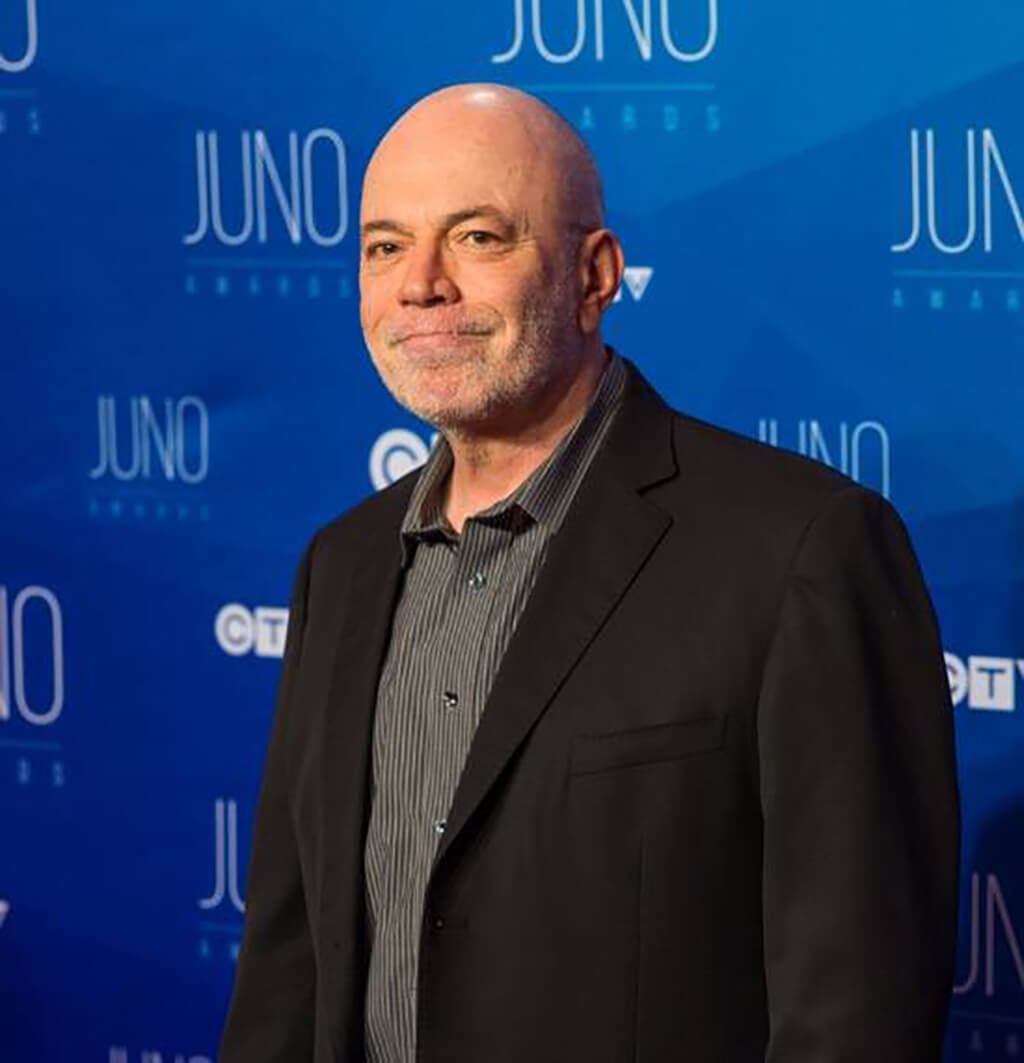

Just over a week ago, Toronto composer Christos Hatzis accepted a Juno Award on behalf of the team behind his ballet score Going Home Star: Truth and Reconciliation. His appearance was unscripted — the award was destined primarily for Steve Wood, the Northern Cree Singers, and the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. Thus, Hatzis had not been named as the representative of Going Home Star — until a real-time Twitter movement propelled him onto the Juno stage, with mezzo-soprano Krisztina Szabó leading the charge.

- LISZTS | 10 Reasons To Miss A Performance - April 24, 2019

- INTERVIEW | Nico Muhly: Opera’s Renaissance Man - November 8, 2018

- INTERVIEW | How An Iranian Musician Has Created A Revolution In Persian Classical Music - October 7, 2018

Within the classical music community, many view this as a victory for them in a market saturated with pop stars. For Hatzis, this event sits harmlessly within a larger — and radically different — outlook for classical music.

The morning after the ceremony, Hatzis explained the sequence of events: the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra had requested that, should they be awarded the Juno, Hatzis accept it on their behalf; however, the official note on the Juno ballot remained unchanged from “No show” due to time constraints. When Going Home Star was indeed announced as the winner, Hatzis remained at his table, under the premise that the Juno Awards committee had not received the modification request in time.

Fast forward to the next hour, when Christos was called forward by host Tom Power to accept the Juno: “So I guess by that time, they’d processed the Tweets — including Krisztina’s, bless her heart. Someone told me that Twitter was buzzing with her Tweets and I didn’t even know of course that she was doing any of that […] she thought [the incident was] just kind of a gross neglect of some kind, which may have felt that way to other people, but it was just protocol.” All told, was Szabó the person who got him on stage? “Totally.”

By now during our talk, Hatzis is anxious to move past the Juno kerfuffle. And so he begins recounting the broader issue for classical music that the incident brought to light, which he had only begun to tell in his Juno acceptance speech the night before.

Ever gracious to his collaborators, Hatzis first tips his hat to the rest of the Going Home Star team. He highlights the work of the Northern Cree Singers, who garnered their first Juno Award only after seven Grammy nominations. Above all, he is hopeful that this will usher in a broader concept of classical music: “They’re a traditional powwow group which means that in the First Nations culture, they are the classical musicians […] so I was actually glad that [Going Home Star] won because it brought to life the fact that artists not only play classical piano – they do powwow, or they throat sing; they do other things, together with an orchestra.” Hatzis draws further parallels between a demographic and a musical genre which are both underrepresented: “In some ways, classical music has become the invisible player at the Junos now, the category that doesn’t matter. But if we could redefine it, where we celebrate classical as any kind of genre that has survived the test of time, then I think that would revitalize our field as opposed to anything else.”

Hatzis is certainly doing his part to improve the visibility of different musical cultures: “My newest piece, Syn-Phonia (Migration Patterns), is about climate change and it has an Arabic singer, an Inuit throat singer, and the Winnipeg Symphony, plus VR [virtual reality] and 3D animation. Tiffany Ayalik [a member of 2017 Juno-winning duo Quantum Tangle] is a new breed of throat singer who actually reads music. What I wrote for her would have challenged a classical singer; she was throat singing in Balkan meters like no other throat singer would be able to do, with all sorts of rhythmic complexity and accompanying the orchestra in weird ways. Basically, she became an integral part of the compositional thinking of contemporary music, which before was just impossible to be able to do then […] So I’m trying to redefine, in some ways, what we all do in ways that become relevant to people outside of the field which is shrinking otherwise.”

Like many proponents of classical music, Hatzis wants to bring the genre out of its Eurocentric mentality, towards a diverse listener base. He foresees increasingly blurred lines between different genres down the road — “and that’s the best thing.”

Technology certainly breaks down barriers, but Hatzis laments that “we [as classical musicians] don’t actually understand that, and we don’t make any concrete effort to explore this phenomenon. Participants of every other genre do, because that’s how they operate, that’s how they think of themselves as social contributors.” And how about targeting live audiences? “We think of ourselves as ‘where’s the next commissioning grant going to come from, who’s going to be on the jury, will they panic because they think we’re moving in some other direction?’ This kind of protectionist attitude never helps the arts, and definitely not in the long term. Somebody may get grants and be successful and stuff like that, but it is [of] growing irrelevance unless you have an audience to which you’re accountable […] [At the moment] we’re simply accountable to arts councils, but as it just happened in the United States, they may not be there at all tomorrow. It can actually end with an executive order from a crazy president.”

It is a vicious cycle, and instead of conceding to governmental stipulations, artists need to take stock of the situation and break free from it. “There are populist politicians in Canada as much as [in] the United States […] so instead of cultivating politicians, you actually need to be cultivating public will, and we are not really doing well on that front.” Hatzis reflects on how much ground there is left to cover: “I think classical musicians depend more on an institutional existence rather than musicians of any other genre […] But we do have a sense of entitlement which does not serve us well. Because we do not necessarily have the survival instinct to look for an audience the way other musicians do.”

Years before winning his first Juno, Hatzis had already developed an incredible acuity for the Canadian musical landscape. He did not like what he saw: “I’ve been ringing the danger bells for years at CBC when they were only playing classical musicians and nothing else [despite how] I was one of the biggest beneficiaries of that fact – I could just call the broadcast centre and say ‘I have a project that I want to do in your best studio’ and they would say ‘OK’ […] I said to CBC, ‘You’re a national broadcaster, you have a national mandate’ – I had friends who were in world music or another place, brilliant musicians, and the front door was closed to them just because they worked in a different genre.”

But how to open up classical music, a tradition inherited from Europe with centuries-old performance practises? Hatzis reaffirms: “It’s just [to] think in terms of serving an audience. It’s wrong to think that our genre requires particular skills […] Every genre has some code; the reason the heavy metal fan likes heavy metal is because they understand something about the code and they build a sense of community around it. That band then is going to survive whatever government comes into power, because the community that has built around it is sizeable enough to support it […] And yes, you survive these cataclysms, or some people do. There is a lot of fallout. But the point is, why wait in some kind of fatalistic way until the cataclysm happens before you make your art meaningful to people?”

Much needs to be done to bridge the disconnect between musical genres, even among Canada’s music professionals. “I think if there’s a message with [Going Home Star], it’s that a powwow group all of a sudden gets recognized in a classical category, and we need that kind of cross-disciplinary work. […] When they announce the classical winners, there’s one table in the hall with all the classical winners and they just applaud, politely, not even enthusiastically most of the time, and then the other tables are just completely clueless, but if you’re talking about any other pop genres, all the others actually applaud. I mean, rock and rollers may not like hip hoppers, but if hip hop is announced, the rock and rollers applaud. I spent most of my acceptance speech speaking about the Northern Cree Singers and the discrepancy of them being recognized at the Grammy’s but not at the Junos. There was applause coming from all the tables in the hall.”

To bring classical music into a different age, continue exploring the road less traveled. Hatzis references the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra’s New Music Festival and how it is driving an encouraging shift: “they’ve had it for many, many years, […] and so they have actually begun to understand the value of contemporary music not as an excuse because of the requirement by the Canada Council for funding, but because they can actually sell better […] with a certain kind of classical music. There are a lot of contemporary composers now for [the WSO] to recruit a younger audience, that they would not be able to do with Bach, Beethoven and Mozart.

Hatzis is no stranger to pushing the limits. In 2008, the then-conservative Toronto Summer Music Festival commissioned him to write a piece which would resemble noble works by Beethoven or the 1812 Overture. The expectation was that it would fit that year’s theme, In the Fire of Conflict, for their over-60 demographic audience. Hatzis gladly obliged: “Ok I’ll call this piece by the same name, but it’ll be about inner-city violence.” With influences ranging from the death of his daughter’s friend, to networking through MySpace and enlisting the musical input of a rap singer who himself was eluding gang pursuit, he turned out a piece with rap strains blasting through the speakers as percussionists played on stage. “The result was mind-blowing. There were so many that came up to me afterward and said ‘If this is rap music, I should listen to more!’” Hatzis affirms, “I don’t have any problem reaching 20-year-olds and octogenarians at the same time. I think we go into our work with preconceived notions and that’s the killer. We don’t actually understand that music has a power that can transform all sorts of prejudices.”

Hatzis’s creative philosophy is well-founded, and a unique outlet for his world view. “I’m not preaching to other people who their priorities should be. I think artists should just follow their heart, however, they see the world, because if they don’t see it that way they can’t possibly act on it. But I’m mostly talking about how I see the world and how I am.” In the meantime, Christos Hatzis will continue to practice what he preaches for the development of classical music.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and reviews before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

- LISZTS | 10 Reasons To Miss A Performance - April 24, 2019

- INTERVIEW | Nico Muhly: Opera’s Renaissance Man - November 8, 2018

- INTERVIEW | How An Iranian Musician Has Created A Revolution In Persian Classical Music - October 7, 2018

- LISZTS | 10 Reasons To Miss A Performance - April 24, 2019

- INTERVIEW | Nico Muhly: Opera’s Renaissance Man - November 8, 2018

- INTERVIEW | How An Iranian Musician Has Created A Revolution In Persian Classical Music - October 7, 2018