For any given performance at the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, there are 130 copies of each piece of music, one for each chorister. For a concert of small works, there could be 15 or 20 different pieces of music. That’s 1500-2000 pieces of music to coordinate, label, track, distribute and ensure their return before filing back away. The job of a choral librarian is the most underrated, most essential part of a choral administration.

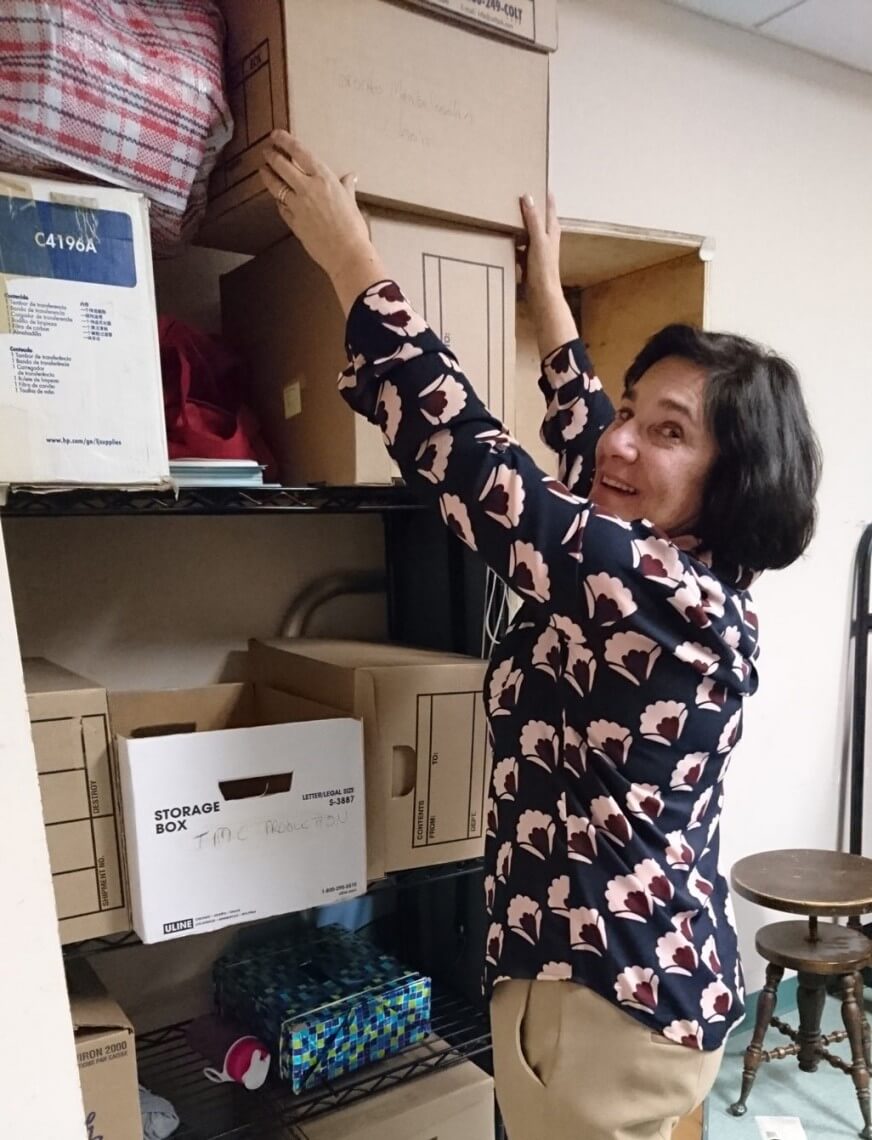

Lorraine Spragg is the librarian of the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir. Serving since 2004, she manages the maintenance, organization, distribution, loaning, and return of 406 works totaling 57,742 pieces of music. With a focus on grand symphonic work, the choir has around 200 copies each of most grand works you can think of like Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, Britten’s War Requiem, Mozart’s Requiem and more.

Spragg came around to the role working in hematology and blood banks. “Organization and accuracy were imperative,” she says, always adhering to the adage “a place for everything and everything in its place.” At Mt Sinai, she established the fetal blood transfusion protocol before becoming an ESL teacher. Her role required a deep attention to detail and extreme diligence. She likens this work to that of being a librarian, but as she says “a mistake in the library isn’t life threatening.” However, being careful with almost 60,000 pieces of music is not an easy or quick task.

Lorraine has been around music for a long time, her husband, Jim Spragg, is a trumpet veteran of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. The Spraggs are known for their musical contracting of orchestras providing live accompaniment to organizations like the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, Casino Rama, the Elora Festival, and Mirvish Productions. Like any orchestral librarian, Spragg also writes in the bowings for the strings according to the concertmaster. These markings can be time-consuming, and she is often annoyed when loaned scores come back with altered bowings. She has to correct these markings back to the preferences of the Choir.

Historical markings in scores are common and sometimes problematic for singers. I once had a Benjamin Britten score that was given to me on loan from a church in Regina. Some keen chorister over there had decided it would be a good idea to highlight, in yellow highlighter, every single Alto line in the piece. As a Tenor, this was an unhelpful marking. With pieces on loan, I’m often surprised that someone would mark music in anything other than pencil.

I spend a lot of time marking my scores, and as such, like to purchase copies of large works so that I don’t’ feel guilty giving a book of music back to the library with my chicken scratch all over it. In concert or on recordings, listeners will hear the refined delivery of a particular piece. Yet, choristers must remember the rhythms, the entries, the dynamics, the emotion, the storytelling, the context, and the pitch. All of these things are editorialized by conductors and can be in direct opposition to what is written on your score. Breath marks, tricky intervals, markings for enharmonic or dissonant passages, added emphasis and accents, and more are common. For visual learners like me, writing cues and notes are essential road markers to a successful delivery.

With an ensemble as old as the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, you get sheet music in an “interesting” condition. When the Bach Mass in B Minor was performed in 2014, I had a copy of the music from the 1930s. The spine was cracked with tape holding what little life it had together. It was humbling to think of the dozens of people who had used that score over the course of the 70 years it saw action. The death knell for that particular piece of music came when I got towards the middle, and the binding had just crumbled. The music literally fell apart into a pile of disordered pages at my feet. I ended up buying a copy of my own which will always have my markings.

Lorraine is there right away to help with music on its last legs. She has an arsenal tools to keep the library healthy. Her key tool is thick, clear archival tape that does not crack, dry out, or yellow. For orchestral scores, she keeps rolls of paper-bandage tape that is see-through, durable, and does not decay (a tip shared by TSO librarian Gary Corrin; more on him HERE. She is anti-paperclips, as this damages even the strongest paper, and leaves indentations in the music. The taping of book spines, which Lorraine is careful to do every time, preserves them.

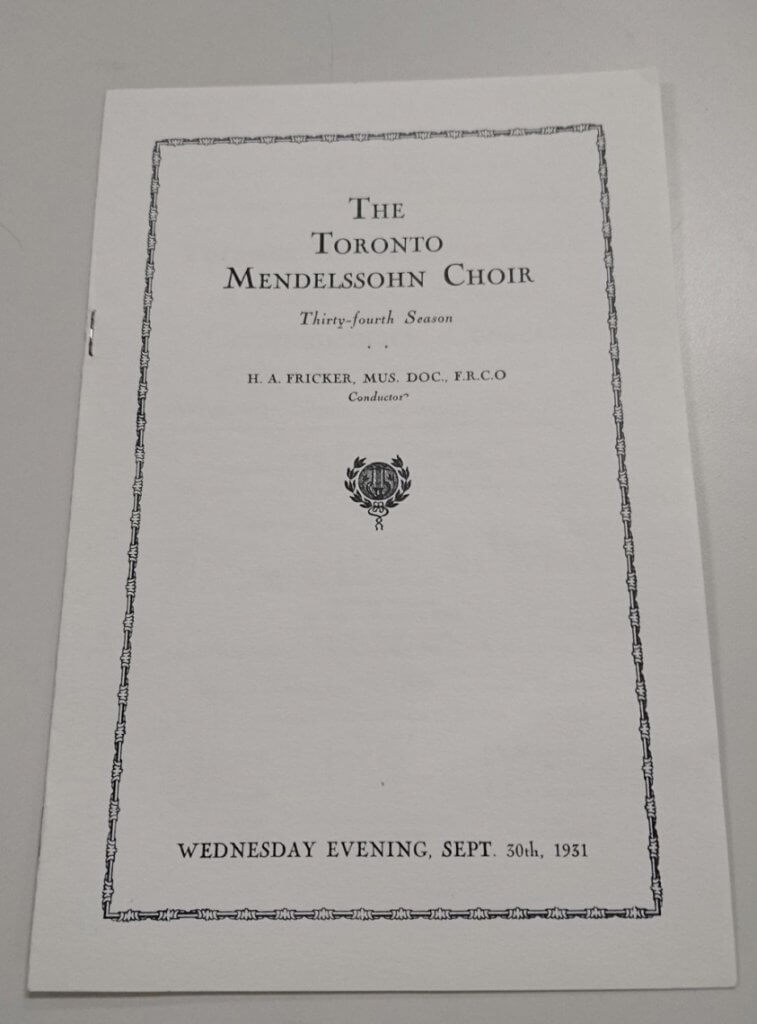

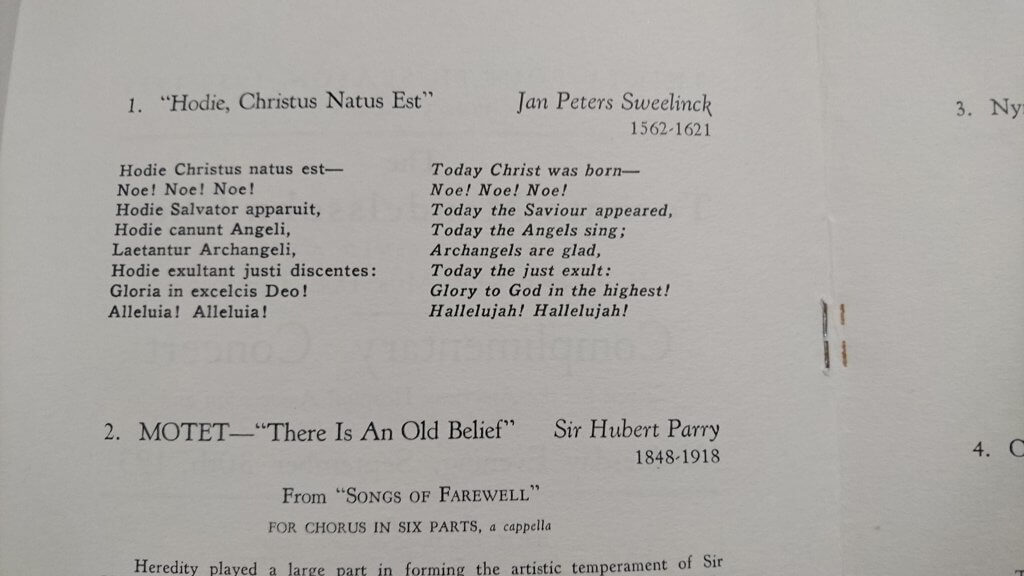

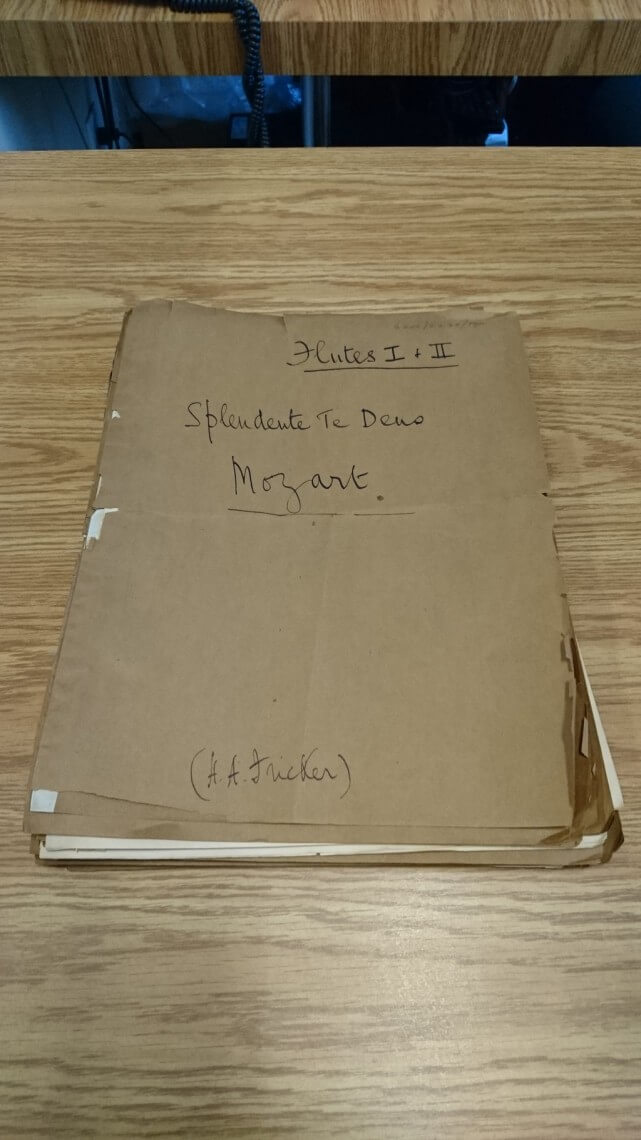

Preservation is important. Over the years Spragg has found interesting pieces of history. Recently, in a Christmas score, she discovered a pristine TMC program from 1931. There are pieces in the historically steeped library that are not easily found anymore. The Choir may have one of the most complete performance collections of Healey Willan’s choral work — many of the scores original or from the mid-century and earlier, some of them written for the Choir. There are scores handwritten and edited by H. A Fricker, the second conductor of the choir between 1917 and 1942.

Keeping the music in good order is just one part of the process. Distributing the music to 130 choristers is another massive task. In the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, each chorister has a unique number associated to their voice type and section. That means each piece of music has a little label with the number on it to correspond to a specific chorister. For a concert with many small pieces, that could mean 10 or 15 labels per chorister. Spragg manually applies 1000-1500 labels to make distribution and filing consistent.

“I store the music in the boxes in “score order,” soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. Everything is set up so that I can pull out a set of music and have it ready for use in a short while. Without this organization it would take hours to prepare a set of several pieces”, says Lorraine. She’s so organized that you’ll receive the exact same piece of music if the choir performs the same song in future seasons. This organization also ensures that the bulk of the work only needs to be done the first time a song is added to the library.

The Toronto Mendelssohn Choir performance library is also unique in that external organizations can request a loan of the music. Each year, about 50 different requests for loans come through to the choir everywhere from California to right across Canada. Popular requests include Lydia Adam’s arrangement of We Rise Again, Derek Holman’s Night Music, and many of the grand symphonic works. While hard to say for sure, it may be one of the most active libraries of any performing choir in North America.

The next time you see any choir in action, think about the work that goes into preparing for success – it takes a village, a solid librarian, and kilometres of archival quality tape!