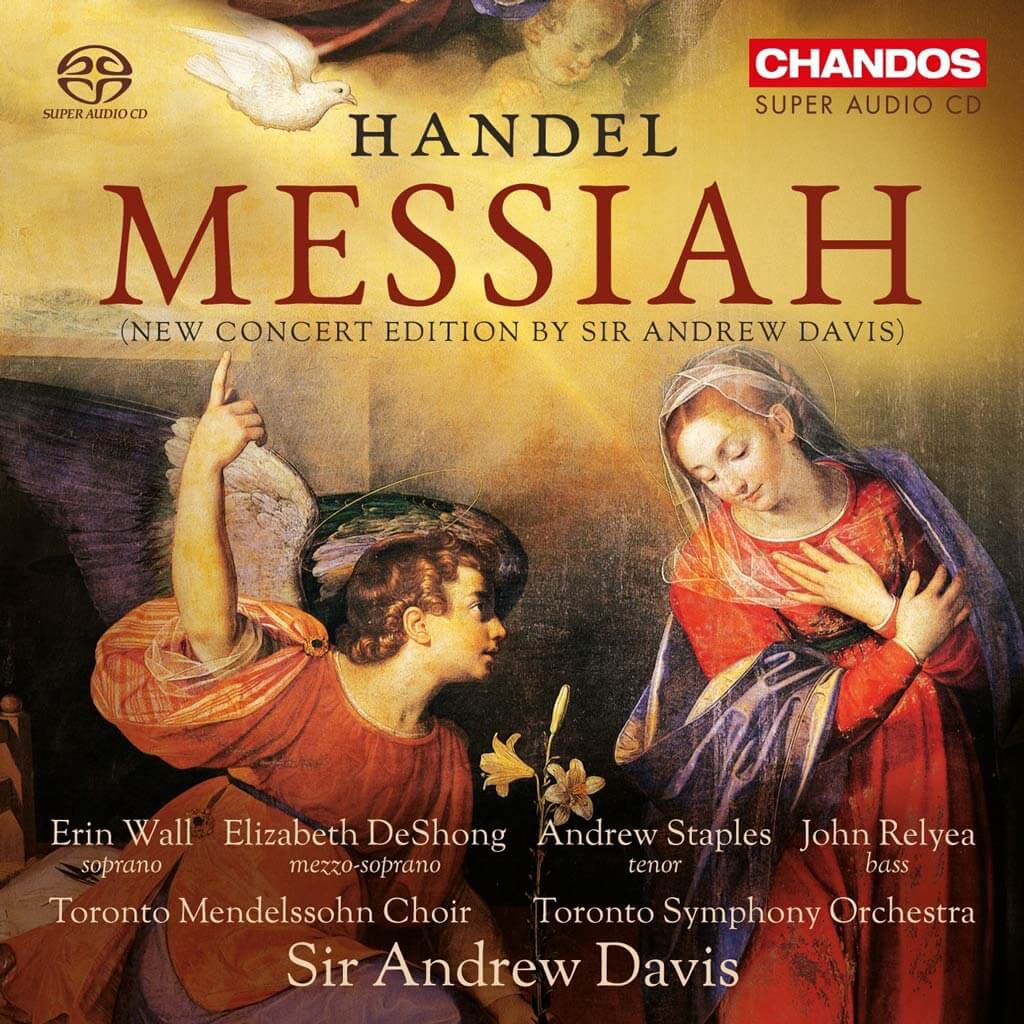

Handel’s Messiah has been with us for a very long time. A work clearly beloved by millions of people, its presentation is an annual Christmas event in many cities.

So why mess with it? People love it the way it is. What moved Sir Andrew Davis to rewrite the piece? Surely it is the height of arrogance for Sir Andrew to think that he can make a great work greater by making wholesale changes in the score. I would have thought that the conductor’s job is not to re-compose Messiah but rather to make it as great as it can be by playing what the composer wrote as he intended it to be played.

The notes for this new Messiah were written by Sir Andrew, who obviously felt the need to justify his “new concert edition” — as well he should. In his own words: “My aim was to keep Handel’s notes, harmonies, and style intact, but to make use of all the colours available from the modern symphony orchestra in order to underline the mood and meaning of the individual movements.”

Unfortunately, this explanation begs the question and suggests that in its original form Handel’s music (orchestration) fails “to underline the mood and meaning of the individual movements.” When I was young, Messiah was usually performed in the Victorian era Ebenezer Prout version (1902), using a large chorus and orchestra. Then in 1965 came the Watkins Shaw edition, which got back to Handel’s original version, and generated a new tradition.

British conductor and impresario Sir Thomas Beecham (1879-1961) had been making his own arrangements of Handel’s music for many years and in collaboration with fellow conductor Sir Eugene Goossens (1893-1962), produced a version of Messiah for modern orchestra that went far beyond what Prout had done. It was technicolor, if you will, compared to Prout’s black and white Messiah. That recording is still something special (RCA 61266) and not the least of its virtues was tenor Jon Vickers.

Sir Andrew Davis has now given us a version of Messiah far more elaborate than Prout’s and more circumspect than the Beecham-Goossens. Handel, in his original version, limited his orchestration to strings, oboes and bassoons with trumpets and timpani used occasionally, as in the “Hallelujah Chorus.” Davis adds flutes, clarinets, horns, trombones and a lot of percussion — and a commensurate number of strings. Handel also used a keyboard continuo — probably a harpsichord. In the Davis version, an organ is used throughout in this role.

On the whole, the Davis re-orchestration is done very conservatively. In many movements, few listeners will notice any differences at all. In others, Davis limits himself to a few added winds here and there, trombones to reinforce bass lines and full on brass and percussion only at cadences.

Among the Davis touches which really stand out are the lovely oboe and flute solos in “How beautiful are the feet,” the solo clarinet in the soprano aria “I know that my Redeemer liveth, “ and a snare drum used tellingly in the tenor aria “Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron.”

No doubt having decided that Handel’s original version with festive trumpets and drums was effective enough, Davis has pretty much left the “Hallelujah” chorus alone. In the bass aria “Why do the nations so furiously rage together,” he adds winds and percussion, where he surely could have done much more, given the strong emotions at play. Similarly, in the mezzo-soprano aria “He was despised and rejected of men,” he could have, but did not, add some dark colours in the orchestra to underline the emotions expressed. Admirable restraint or a missed opportunity? It depends on how one looks at the entire project.

In my view, the changes in orchestration introduced by Davis add little to the effectiveness of Handel’s original orchestration. If one is going to undertake such a revision there ought to be an obvious need for it as there is, for example, in the case of certain operas by Monteverdi or Cavalli; in the case of Handel, there simply isn’t such a need. On the other hand, if one simply wants to do Messiah with a modern symphony orchestra, why not go all the way? Prout went part of the way, and Goosens gave us the real thing. This is not to say that Goosens gave us a ‘perfect’ modern orchestration — I agree with Davis that it is occasionally “overblown” and “vulgar” — but at least he gave us total immersion.

Several years ago, Davis did his own orchestration of Bach’s organ piece, the Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor. It too was much too timid in the use of the modern orchestra; Leopold Stokowski’s version, by comparison, was far more imaginative — indeed, magnificent.

Apart from the orchestration, Davis’ conducting approach to Messiah is a curate’s egg. From the opening bars of the Overture, we note that while Davis often has the strings play with little or no vibrato in accordance with what we now take to be historical performance practice, he also tends to take tempos that are a throwback to the ‘bad old days.’ The Allegro sections in the chorus “Since by man came death” are positively plodding by today’s original instrument standards.

This recording, based on live performances given in Toronto in December 2015, benefits from the spontaneity of actual performances. On the downside, however, are problems of execution that can sometimes and sometimes not be fixed with post-concert retakes. I have to wonder if soprano Erin Wall, for example, was in the best of health during these performances. Her vibrato is often excessively wide, and she often seems to be lunging at notes above the staff. Bass John Relyea, who also seems to be operating at less than his best, sounds uneasy in some of the melismatic passages and his top E’s in “The trumpet shall sound” are very thin. Producing a sound that is often woolly when it should be crisp and well-defined, the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir also appears to have slipped a notch or two.

The Alternative Recordings

Earlier in this review, I mentioned the Watkins Shaw edition of Messiah and how it changed our view of the piece. Among the first recordings to adopt this “new” and leaner approach to Handel’s great oratorio were those conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras (Warner Classics 69449) and Sir Colin Davis (Philips 438346); both recordings were released in 1966 and still sound fresh and joyous. Later, we had a substantial number of recordings using original instruments, among them a fine one conducted by Sir John Eliot Gardiner (Philips 434297), featuring Canadian mezzo-soprano Catherine Robbin.

It should be noted that Sir Andrew Davis with the Toronto Symphony and the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir recorded Messiah for the first time way back in 1987. This was a ‘middle of the road’ version using more or less Handel’s original orchestration, a large chorus and orchestration, but making no attempt to sound historically informed. All in all, this earlier recording, with an outstanding performance by soloist Kathleen Battle, was a better rendition of the work than Davis’ “New Concert Edition.”

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and reviews before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

- SCRUTINY | TSO Lets Berlioz Do The Talking In Season Opener - September 21, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Even Yannick Nézet-Séguin Can’t Make Us Love Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito - September 6, 2018

- RECORD KEEPING | Giovanna d’Arco With Anna Netrebko Explains Why The Best Operas Survive - August 30, 2018