- REPORT | Ukrainian Pianist Crowned Winner Of 2022 Honens Competition - October 29, 2022

- REPORT | The 10th Honens International Piano Competition: Finals I - October 28, 2022

- REPORT | The 10th Honens International Piano Competition: Semifinals IX-X - October 25, 2022

New York City, The Metropolitan Opera. Iolanta / Bluebeard’s Castle

Wear a down parka to the Met in winter for a Slavic double-bill like Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle and you feel like the only caveman too stupid to club a mink. A sweet Russian lady handed me her spare with maternal concern, but if I felt any embarrassment it vanished in the dead animal’s embrace, and people stopped staring.

It began with a deer being stalked and killed by lasers, then our blind princess Iolanta wakes up in her room under her bed beside a wall of trophy heads. Was she having a nightmare or watching Aliens vs Predator? Or are we the only ones who could see the deer? This is the ambiguity—who sees the truth—that director Mariusz Trelinski spears through his double bill.

The same production of Tchaikovsky’s opera opened in Saint Petersburg in 2009 (with Anna Netrebko, also in the role), but then it was paired with Rachmaninoff’s Aleko instead of Bartok’s hallucinatory Bluebeard. Like arguing philosophy with undergraduates, the evening was crudely invigorating. Even if the new combination simply doesn’t sustain Trelinski’s idea that Bartok’s “Judith continues the story of Iolanta”, judging from the reviews of the opening night, it has improved. Gergiev’s tempos weren’t slow at all.

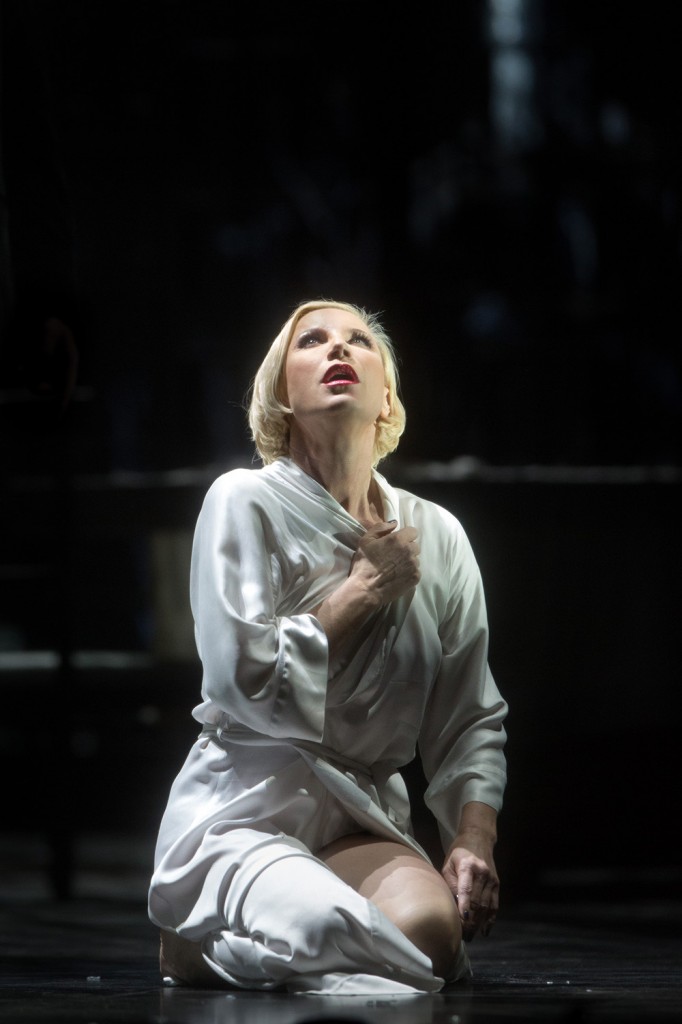

The hunting trophies in her room introduce Iolanta as someone between pampered princess and prisoner, an image that is reinforced by uniformed nursemaids whose manners suggest a sanitarium. Two of them even mock her blindness before dressing her in a long-sleeved gown like a straightjacket and putting her in bed. When she thanks them for the attention, her “How can I ever repay your kindness” has a dark colour that’s only half Netrebko’s ungirlish huskiness—especially when compared to herself six years ago. It complicates Iolanta’s character, but the Russia star still has her part by the throat.

The men were weaker. Playing the king’s messenger, Alamic as a comic character suited Keith Jameson’s atrocious Russian but not the opera, and Ilya Bannik’s Saturday cover for a sick Alexei Tanovitski as King René was weirdly refrigerated. He cried to God while holding his stomach—does he have a tragically blind daughter or indigestion? Elchin Azizov was much better as Ibn-Hakia, though his straightforwardly thrilling aria didn’t rouse the audience, who only stirred for Aleksei Markov as Robert and Piotr Beczala as Vaudemont.

These upper-class twits arrived holding skis despite the absence of snow, but Markov brought a rough, bright impulse to the stage, like a freshly sharpened edge before you take off the burr. Beczala was more subtle and shapely, though occasionally strangely narrow. Robert’s aria is about his frustration that he can’t marry a more exciting woman because he was engaged to Iolanta as a child, while Vaudemont gets to defend a simpler feminine ideal that’s conveniently met by a woman who’s been kept in the dark. Iolanta’s purity seems to derive from her ignorance. Beczala’s performance of the aria, which Tchaikovsky added at the request of tenor Nikolay Figner, got the first applause.

When Vaudemont accidentally breaks the taboo and tells Iolanta about colour and light, she defends her blindness, astonishingly, as no worse at detecting God’s splendour. This intriguing idea is interrupted by King René and a search party with flashlights that caused temporary blindness and announced the bizarre finale. It starts well. Vaudemont is sentenced to death unless some unspeakably painful treatment by Ibn-Hakia succeeds. “He’ll die if you can’t see!” We’re riveted, then everything resolves. The tension evaporates and the remaining time is lavished on an asinine chorale that Trelinski takes à la Book of Mormon with dazzling rays of light behind a marching chorus of caterers as snow flutters down. The last thing the audience did was laugh.

Bluebeard slapped us back into the serious with a creaking night-time forest and a prologue (often-cut) growled in Hungarian by a heavy smoker. Then we saw Bluebeard taking his new wife Judith to their home, which is a garage in the woods with a serial killer vibe. This is where Judith sings of love and “warming the stones” with her body.

Nadja Michael and Mikhail Petrenko were irreproachable. It is a difficult opera propelled by its music, so a sense of acting, even of physical presence, doesn’t come naturally. Bluebeard only echoes Iolanta with the lines “What are roses? What is sunshine?” But even if Judith won’t follow the thought, there is an interesting tension in this production between what we see in Bluebeard and what is described. Judith sings of treasure from a bathtub, of gardens from a dining room with a bouquet, and of a flat white sea from inside a cell. So who sees the truth—her? Bluebeard? Or us? Iolanta raises the same question when she chastises Vaudemont for presuming that only the sighted can recognize God.

Judith wants to know what is behind the seven locked doors of Bluebeard’s castle and at first it seems that she will have to convince him, but he’s handing over bunches of keys almost immediately. Bartok won’t release your attention; it’s not clear who is in control and you don’t give a damn about either character anyway. Eventually Bluebeard seems to get excited by the exposure, but when he echoes Judith’s love lines it is with the ardour of a banker. Then he puts on a black glove and does Thing T. Thing from the Addams Family, and even though it makes you cringe, you understand the director’s desperation.

When Bartok submitted his opera to competitions it didn’t win despite his personal popularity, and research has shown that the indifference of Bela Balazs’s libretto disqualified the opera before its music could even be considered. Trelinski tries intrusive projections, flippant strobe lights and recorded sounds to structure the narrative against the foggy resistance of the written work, but the visuals aren’t complex enough to relieve a confused audience.

The opening forest scene returns before each door is opened, which is in addition to the written transition scenes that Trelinski has set in an elevator. The grey shaft suits the industrial setting, but he doesn’t do anything with the potential of Judith and Bluebeard trapped in cramped space. Escape is impossible but the seven doors just end up as a laborious catalogue of symbolist images—until Bluebeard pulls Judith’s body out of a fresh grave and kisses her, sending singing Judith to wander the forest with the spirits of his other murdered wives. The moment she pales and goes quiet is the strongest in the opera, which ended with light applause and a rush to the doors.

“What was that?” Asked my neighbour while she put on multiple generations of foxes. Good question, but I’d see it again. Iolanta/Bluebeard will be broadcast live on February 14th.

- REPORT | Ukrainian Pianist Crowned Winner Of 2022 Honens Competition - October 29, 2022

- REPORT | The 10th Honens International Piano Competition: Finals I - October 28, 2022

- REPORT | The 10th Honens International Piano Competition: Semifinals IX-X - October 25, 2022