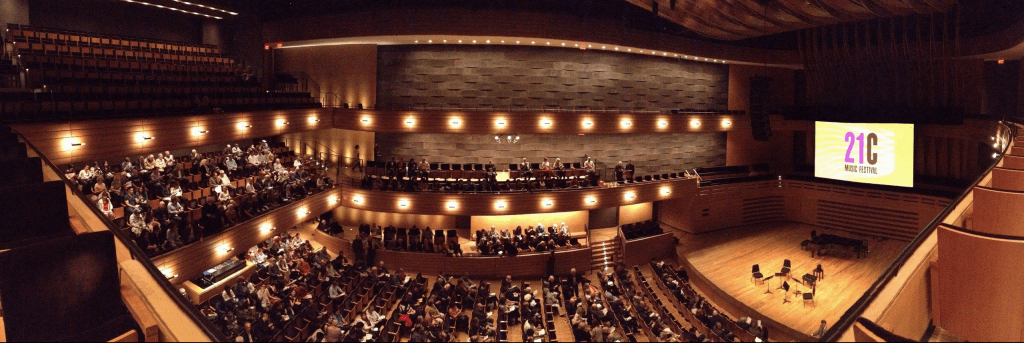

The second evening of the Royal Conservatory of Music’s 21C Music Festival contained a wealth of music for strings, brilliant performances by budding artists, and most attention grabbing, an abundance of incest.

The first performance of the evening was Greek-Canadian composer Christos Hatzis’s third string quartet, The Questioning. Most of Hatzis’ recent music grapples with postmodernism, multiculturalism and its often-tenuous relationship with Western classical music. Hatzis’ string quartet, which opens with a recording of Greek Orthodox chant, blends elements of Eastern music and contemporary classical form and techniques. Extended techniques on the strings conjured images of both contemporary classical music and non-Western instruments; expressive portamento recalled the quarter-tone slides of Eastern vocal techniques, as well as late Romantic string quartet music. The overarching form of the quartet’s three movements, though cast as a cyclical spiritual journey, ultimately recalled the traditional Western musical narrative of exposition, development and tension, and eventual resolution. Despite the extra-musical narratives of spiritual struggle, the strongest characteristics ultimately lay in the quartet’s traditional form, which produced an utmost musical clarity.

The following piece, Brian Currant’s Faster Still for string quartet, piano and violin soloist, acted as a foil to Hatzis’ expressive quartet with its moto perpetuo of flurrying string and piano arpeggios. The irresistible energy of the piece was hampered slightly by Currant’s sluggish direction, though this setback was remedied by a strong youthful performance by musicians from the RCM.

Following this piece was R. Murray Schafer’s curiously functional Quintet for Piano and Strings. The piece rang with a faux-serious Neoclassicism, including rapid scalar dialogue in the first movement, a tortuously bare second movement, and a jocular, Shostakovich-esque finale. The ARC ensemble performed the piece with a seasoned mastery.

In many ways, Louis Andriessen’s monodrama Anaïs Nin is doomed to a marginal existence. No matter how artfully it is performed, this work would make the hair of even the most experienced opera goer stand on end, with its weird blend of incest and intense sensuality. Regardless of this fundamentally challenging subject matter, the work remains intriguing in context with contemporary vocal music and the rest of Andriessen’s musical work.

The work is scored for amplified mezzo-soprano, an ensemble of winds, double bass, piano and percussion. Wallis Giunta as Anaïs Nin conveyed a multi-faceted personality in her performance, capturing the confused, lonely and burning passion of Nin’s artistic personality. Giunta’s voice had a brassy and precise quality, which exquisitely matched the chunky accompaniment of Andriessen’s scoring. The monodrama portrays Anaïs Nin recalling her times with past lovers, which included author Henry Miller, her psychoanalyst René Allendy, actor and playwright Antonin Artaud, and ultimately (and most scandalously) her own father, the composer and pianist Joaquin Nin. The production centered rounds a sinful-looking red couch, which Anaïs frequently lolled around on while shockingly recalling the dangerous liaisons with her father.

At a surface glance, forbidden desire appears to be at the centre of Andriessen’s Anaïs Nin, but more vital is the pleads of a lonely and insatiable artist, one whose hunger for passion and drama are only sustained by a self-destructive mania.

+++

The RCM’s 21C Festival continues with events running until May 25th, 2014.

Tyler Versluis

- PREVIEW | U of T Faculty of Music Brings Salvatore Sciarrino to Toronto - January 27, 2017

- PREVIEW | The Music Gallery Gears Up For The Viking Of 6th Avenue - November 25, 2016

- SCRUTINY | Esprit Orchestra Salutes The Legacy Of R. Murray Schafer - October 28, 2016