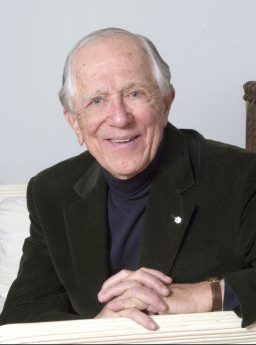

Toronto composer John Beckwith is perplexed. People keep asking him to write new music, but he doesn’t get to hear much of what he wrote before — and there is a lot, given that the vigorous 86-year-old has been composing professionally since 1947.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

In October, Beckwith wrote to me: “After more than sixty years of composing, I find my music is seldom performed, but it happens that next month in Toronto there will be two first performances within the same 24-hour period.”

The first is a concert on Thursday by Montreal early music specialists, Les Voix Humaines. On Friday, Nov. 22, at a lunchtime recital at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church next door to Roy Thomson Hall, clarinetist Peter Stoll and pianist Adam Zukiewicz premiere Follow Me.

Les Voix Humaines, who normally play early and baroque music, commissioned Beckwith to write a piece for an afternoon concert presented by the Women’s Musical Club of Toronto. The programme is built around the passing of seasons and includes soprano Suzie LeBlanc.

Beckwith’s piece is entitled After Simpson — not Homer, but Christopher, an English composer associated closely with the viola family, which was enjoying a last flourish of popularity before being supplanted by the violin family. Simpson died in 1669, leaving behind a book key to understanding music for viol consorts: The Division Viol, or the Art of Paying Upon a Ground.

So, before writing a single note for Les Voix Humaines, Beckwith read Simpson.

“I’m very curious and interested,” says Beckwith of early and baroque music. “What kind of common ground can I find with the period instruments?”

He’d heard Voix Humaines gambists Margaret Little and Susie Napper play Simpson’s fantasias at a concert years ago. “I was knocked out,” says Beckwith. “I didn’t know the music of Simpson at all. It was different from most baroque music; it comes from figured-bass style as well as the English fantasy tradition [best known to us through the chamber music of Henry Purcell] and I thought, what’s special about this?”

“So I tried to do something rather in the way Simpson went about writing,” Beckwith explains. This meant trying a piece with a clear theme followed by variations known as divisions, where the theme gets broken down into shorter and shorter notes — “almost like a raga,” adds the composer, whose interests have long gone well beyond the here and now.

I suggest to him that perhaps the reason why he gets a lot of commissions, but not a lot of repeat performances is because there’s no signature Beckwith sound or aesthetic; each piece is something new onto itself.

“I think what you say is right,” he replies. “Eclectic is what they call me. I’ve always said that each piece is a different problem, a different project, and is makes its own rules, in a way. It sets its own principles on whatever you start with.”

Beckwith is an intellectual and aesthetic pack rat. “I pick up things. I listen to a lot of music,” he says. And his compositions are as diverse as their inspirations — and their commissioners.

Another new work — Tanu, scheduled for a Montreal premiere next March — was inspired by a visit to Haida Gwaii in British Columbia last summer, where he marvelled at the great totem poles, inscribed with local history and colour of people long departed.

Unlike the rest of us, Beckwith doesn’t just consume what he encounters, but makes something new of it. Even something as (relatively) simple as a new folksong arrangement is an excuse for Beckwith to set his imagination into motion.

I’ll pluck just one example from his memoir, Unheard Of; Memories of a Canadian Composer, published last year by Wilfrid Laurier University Press. In the chapter on music for voice(s), Beckwith writes:

From various arranging assignment (including those for the CBC and for the Music at Sharon concert [where Beckwith was the original artistic director]), I found I had developed a technical approach to traditional songs and dances. I avoided composing standard harmonies on the original tunes, but relied instead on first observing the original, and then developing supporting lines and counter-melodies from it — that is, from its interior harmonic implications, its range and repertoire of pitches, its characteristic intervals…

In short, nothing is taken for granted in Beckwith’s cosmos.

But contrast that to the way the rest of us operate: We walk into a Starbucks, a McDonalds or a Tim Horton’s anywhere in the world and get the flavour and consistency we are used to.

Mention “Mozart” or “Chopin” or “Beethoven” or “Verdi” to someone and you’ll get a flicker of recognition, perhaps even a smile at a recollected favourite piece or tune.

Let’s think for a moment of the most successful composers of our time: Arvo Pärt, Philip Glass, John Williams, John Adams or Eric Whitacre, just to name a few living ones. Like that Starbucks pumpkin latte, we know what to expect. Once we’re hooked, we can return to their sound worlds safely without any great worries of unpleasant surprises.

Of course each piece is new and different, but they share traits that are easily heard and appreciated.

John Beckwith, on the other hand, presents us something new based on an imperative of what fits the needs and context of this piece, not on the needs of an audience or a tradition or of any other sort of external expectation. Just as he challenges himself, he challenges his listener as well.

Think of Beckwith as the bespoke tailor, while the others are, to over-generalize, more like off-the-rack.

Does a consistent aesthetic trump bespoke composition? The answer is yes, if popularity is the aim.

+++

For more information on Thursday’s Women’s Musical Club of Toronto concert, click here.

For more information on Friday’s lunchtime concert at St Andrew’s, click here.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019