There is one week left to catch Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s sound-intensive installations at the AGO — including her famous Forty Part Motet in the Moore sculpture gallery, a fine setting to hear Thomas Tallis’s 16th century gift to Western music.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

Tallis’s music has had a small bump in notoriety over the past couple of years as that motet, Spem in alium, is also part of the soundtrack to amorous adventures in Fifty Shades of Grey.

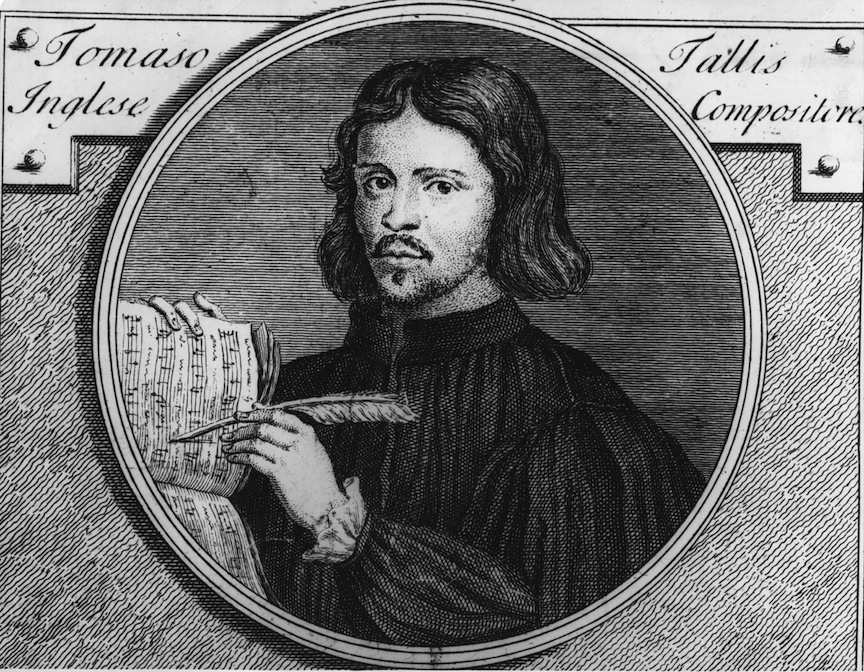

There is much, much more equally seductive polyphony — most of it sacred — that flowed from Tallis’s quill, using fewer voices.

Tallis, if we knew more about him, would likely have made a fascinating character study. He was the ultimate political survivor, born and first employed as a Roman Catholic and yet a successful church musician in the Chapel Royal to Protestant monarchs as well — at a time when religious allegiances were frequently a matter of life and death in court circles.

His epitaph, written at his death in 1585, is a tribute to dedication and survival:

Enterred here doth ly a worthy wyght,

Who for a long tyme in music bore the Bell;

His name to shew was Thomas Gallys [sic] hyght;

In honest vertuous lyff he did excell.

He served long time in chapp … with grete Prayse

Fower Sovereygne’s Reygnes (a thing not often seen),

I mean King Henry and Prynce Edwarde’s dayes,

Quene Mary and Elizabeth our Quene.

Fortunately for Tallis, a contemporary — a Dr Cooke — set these words to a glee. The church where Tallis was buried in Greenwich was torn down in the late 18th century. The epitaph as well as his tomb disappeared, but when the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association laid out St Alphege Churchyard in 1889, the song allowed them to reproduce the words on a memorial plaque (there is no actual tombstone or remains there).

Here’s a fun little Canadian connection: Gen. Wolfe of Plains of Abraham fame was bured next to Tallis at St Alphege’s in 1759.

Tallis left two distinct styles behind: Latin choral polyphony for the Romans and straightforward English settings for the Anglicans.

The two sides of this legacy are most marked with these two pieces, a heavenly setting of Videte Miraculum (recorded very nicely by Stile Antico) and (for the purposes of irony, not musical quality), the hymn All Praise to Thee, My God, this Night, sung by the Piedmont Singers at St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin last summer:

Tallis wrote music for home use, as well. Some scholars believe that his Lamentations of Jeremiah, another of his finest choral creations, is code for the fate of Roman Catholicism in England. Here are four Lamentations sung by the Choir of New College, Oxford, led by Edward Higginbottom, followed by Kevin Gray playing “Fond Youth is a Bubble,” a piece Tallis wrote for the virginal, preserved in the Mulliner Book:

There is so much more of Tallis to savour. Listen to how much the composer can get into four parts, in the Gloria from his Mass for Four Voices, sung here by the French vocal ensemble Camerata Apollonia:

And we can’t leave him without Spem in alium, beautifully sung here by 40 voices, each singing a different vocal part — The Sixteen augmented by the Laurenscantorij — in a Rotterdam concert led by the great Harry Christophers last winter:

If you want to read up more about Tallis, this is a good place to start.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019