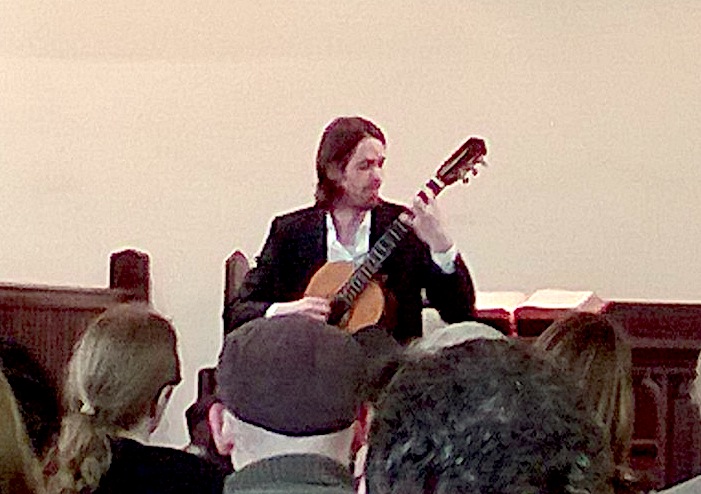

I was at a solo concert given by wonderful Toronto classical guitarist Michael Kolk yesterday. He chatted between pieces, and was almost apologetic about a couple of less conventional works on the programme, worried that we might not like what we hear.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

When you think about it, liking something is a pretty big expectation to put on anyone who takes a chance on a concert of art music or opera.

We don’t like every person we meet, or every movie we see, or every book we read. But the interaction itself still has the potential to change our life in some way.

Columbia Journal managing editor Jaime Green has posted a fascinating discussion on this topic on The Awl (a site whose tagline reads, “be less stupid”). The germ of his post was born when he went to Carnegie Hall to see Gabriel Kahane perform with the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra.

The result, for Green, was something unexpected and unfamiliar.

“I felt like I was missing something. Like I should like this music. Like I should get it,” writes Green.

How many of us have sat bewildered at a concert, silently thinking those very same thoughts? They come from an unfomfortable mix of shame and a bit of guilt — two emotions that should have no place in an environment of true sharing.

We all know or have heard enough times that the more we sample different types of music or visual art or literature or theatre, the easier it becomes to appreciate differences.

But does that mean liking, in the traditional sense?

No.

One personally helpful item I took away from both Kolk’s recital yesterday and Green’s online discussion was the use of the adjective “crunchy” to refer to dissonance, a term that is emotionally freighted for most people. Crunchy is neutral, yet very evocative — like hearing the term “pitchy” on a TV talent competition.

But that’s the tiniest of details. The actual issues are much broader.

Here’s a telling section of Green’s exchange:

Jaime: If I came to this without any sort of personal investment, I might’ve left thinking, “That was weird. I’m probably not gonna do that again.” I mean, Carnegie itself is a pretty lovely place to see a thing. And this made me want to learn more about the WPA Guides to the States. But the one moment that inspired a “more like that, please” response in me was when the entire orchestra — all these adult people, seeming like serious musicians (Gabriel didn’t seem unskilled or unserious but he was there with his shaggy hair and young self and wide-lapelled blazer and jeans) — the one moment was when the whole orchestra set down their instruments and stood up and sang in a chorus. I had no idea what was going on, but I knew that I liked it.

AUFWKCCM: So do you think that the formality of the rest of the experience, besides the prettiness of Carnegie, is sort of a turn-off?

Jaime: No, I like that. It’s fun, like playing dress-up. I liked going to the bar beforehand and seeing all the old people in their fancy clothes, and me wearing Converse with my dress-up clothes.

AUFWKCCM: A-ha! That’s really interesting to me, because it comes up a lot when I’m talking to people about how to create an experience that “young people” or “cool people” will be excited about. The problem, of course, is that it’s not as simple as like putting serious music in casual spaces, because people like the dress-up experience, too. BUT, I think it creates a situation that doesn’t foster a lot of interest in experiencing more of that Difficult Music. I think it creates a situation where even smart listeners are looking for that moment that you mentioned, when the performance breaks out of the formality. And that’s maybe not the best thing for creating access to the difficult art part of the experience.

This being a Sunday, perhaps you have time to read the full discussion between Green and his musically catholic friend. They cover most of the concerns expressed by anyone concerned about art music and its potential audiences.

And none of it involves actually having to like a piece of music. The post is more concerned with new Western music, but it applies equally to any other time or tradition.

You will find it here.

If you have still more time, have a listen to Canadian composer Andrew Staniland‘s richly evocative Peter Quince at the Clavier, a 2008 setting of a powerful meditation on the ephemeral versus the eternal by Wallace Stevens.

Think about appreciating what Staniland has created, versus liking or not liking the sounds themselves. Then think about both approaches, and how they can sometimes feed each other.

Peter Quince at the Clavier

(from Stevens’ first published collection of poems, Harmonium, from 1915)

I

Just as my fingers on these keys

Make music, so the self-same sounds

On my spirit make a music, too.

Music is feeling, then, not sound;

And thus it is that what I feel,

Here in this room, desiring you,

Thinking of your blue-shadowed silk,

Is music. It is like the strain

Waked in the elders by Susanna:

Of a green evening, clear and warm,

She bathed in her still garden, while

The red-eyed elders, watching, felt

The basses of their beings throb

In witching chords, and their thin blood

Pulse pizzicati of Hosanna.

II

In the green water, clear and warm,

Susanna lay.

She searched

The touch of springs,

And found

Concealed imaginings.

She sighed,

For so much melody.

Upon the bank, she stood

In the cool

Of spent emotions.

She felt, among the leaves,

The dew

Of old devotions.

She walked upon the grass,

Still quavering.

The winds were like her maids,

On timid feet,

Fetching her woven scarves,

Yet wavering.

A breath upon her hand

Muted the night.

She turned–

A cymbal crashed,

And roaring horns.

III

Soon, with a noise like tambourines,

Came her attendant Byzantines.

They wondered why Susanna cried

Against the elders by her side;

And as they whispered, the refrain

Was like a willow swept by rain.

Anon, their lamps’ uplifted flame

Revealed Susanna and her shame.

And then, the simpering Byzantines,

Fled, with a noise like tambourines.

IV

Beauty is momentary in the mind —

The fitful tracing of a portal;

But in the flesh it is immortal.

The body dies; the body’s beauty lives,

So evenings die, in their green going,

A wave, interminably flowing.

So gardens die, their meek breath scenting

The cowl of Winter, done repenting.

So maidens die, to the auroral

Celebration of a maiden’s choral.

Susanna’s music touched the bawdy strings

Of those white elders; but, escaping,

Left only Death’s ironic scrapings.

Now, in its immortality, it plays

On the clear viol of her memory,

And makes a constant sacrament of praise.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019