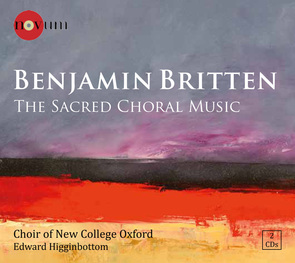

I was hoping that someone would comprehensively visit Benjamin Britten’s impeccably crafted sacred choral music for this, the 100th year since his birth. A new, two-CD album by the Choir of New College, Oxford under director Edward Higginbottom more than fulfills that wish.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

As with Britten’s opereas, this carefully selected set of 17 works for liturgical contexts speaks directly to English-speaking listeners without the need for understanding a single thing about the meaning of either the text or the music.

As Higginbottom puts it in his CD booklet notes: “There can be no doubt that Britten was most truly himself when writing Peter Grimes, the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, and the War Requiem. Though certainly more modest in scale, works such as Hymn to St Cecilia and A Ceremony of Carols [both included on the album] carry with them the same imprint of his genius.”

As Higginbottom puts it in his CD booklet notes: “There can be no doubt that Britten was most truly himself when writing Peter Grimes, the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, and the War Requiem. Though certainly more modest in scale, works such as Hymn to St Cecilia and A Ceremony of Carols [both included on the album] carry with them the same imprint of his genius.”

The music covers all but the last decade of Britten’s compositional life, the last work being the Hymn of St Columba, which dates from 1962. The earliest piece here is a deeply meditative Hymn to the Virgin that Britten wrote in high school.

Here are some California teens singing it five years ago at First United Methodist Church in Palo Alto by the Los Altos High School Main Street Singers Choir:

I spent several formative years singing Britten’s sacred music. After getting over the momentary difficulty of not always being in a consonant relationship with the other voices and/or the organ, I was seduced by Britten’s ability to marry the right melodic twist and harmonic shift with the meaning of the text.

Even in A Ceremony of Carols, the magical set of Christmas pieces for sopranos (boys’ voices, really) and harp, which is among the most concert-like (rather than worship-focused) of the sacred music, Britten never ornaments for ornament’s sake. He was all about making sure every note and utterance had relevance and meaning.

I’ll quote Higginbottom again, because he puts it so eloquently:

If there is one thing that plays into our understanding of Britten’s choral (and indeed vocal) music, it is the quality and character of his musical engagement with the text. This always involved a primary-coloured response to each and every shift in the poetic imagery, allowing at the same time the text to unfold in its natural temporal dimension. Not for Britten, multiple repetitions and complex extensions. As a consequence, he moves through his words with despatch: no sooner has he taken the nectar out of one flower than he is on to the next. It is not surprising that he felt such an affinity with Henry Purcell, whose approach was very similar. For some listeners this is an achievement bordering on the facile, for others it is a rare and admirable talent.

I’m all for proclaiming a rare and admirable talent.

That doesn’t mean that all the music collected here is great, though. The Hymn to St Peter, written for the feast of Saints Peter and Paul, 1955, is a choppy patchwork that tries to smooth out its bumps with a seductive final Alleluia.

On the other hand, there is pure genius not just in the music but in Britten’s choice of text in Rejoice in the Lamb, a cantata he wrote for the 50th anniversary of St Matthew’s Northampton during his enchanted compositional period just before the end of World War II.

The poetry, which comes from 18th century poet Christopher Smart, can soften the heart of even the most cynical 21st century unbeliever. The middle section features solos for treble, countertenor and tenor that centre around God’s other creatures:

For I will consider my cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the living God.

Duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance

Of the glory of God in the East

He worships in his way.

For this is done by wreathing his body

Seven times round with elegant quickness.

For he knows that God is his saviour.

For God has bless’d him

In the variety of his movements.

For there is nothing sweeter

Than his peace when at rest.

For I am possessed of a cat,

Surpassing in beauty,

From whom I take occasion

To bless Almighty God.

For the Mouse is a creature

Of great personal valour.

For this is a true case–

Cat takes female mouse,

Male mouse will not depart,

but stands threat’ning and daring.

If you will let her go,

I will engage you,

As prodigious a creature as you are.

For the Mouse is a creature

Of great personal valour.

For the Mouse is of

An hospitable disposition.

For the flowers are great blessings.

For the flowers are great blessings.

For the flowers have their angels,

Even the words of God’s creation.

For the flower glorifies God

And the root parries the adversary.

For there is a language of flowers.

For the flowers are peculiarly

The poetry of Christ.

Here is the Choir of Christ Church and organist David Hinitt under David Stevens performing two-thirds of Rejoice in the Lamb at Église Sainte-Clothilde in Paris two years ago (the cat, mouse and flowers appear in Part II):

For all the details on this excellent album, issued by New College’s own label, click here.

+++

Another new Britten album I’ve been enjoying comes from Amsterdam Sinfonietta under Glaswegian artistic director and concertmaster Candida Thompson. The label is Channel Classics.

It features Canadian soprano Barbara Hannigan singing Les Illuminations. I’m a huge fan of Hannigan’s, but I have to admit I prefer Shannon Mercer’s work with Toronto Group of 27 in their recent recording of the same cycle. Mercer navigates the French text with much greater poise and power.

Throughout the disc, which includes Britten’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, it sounds as if Thompson wields her chamber orchestra with laser precision. The strings are so precise at times, it’s startling.

British tenor James Gilchrist is fantastic in the Op. 31 Serenade, and I challenge anyone not to melt in the delicious combination of words and music in Tennyson’s poem “Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal,” which closes with, “Now fold the lily all her sweetness up,/ And slips into the bosom of the lake:/ So fold thyself, my dearest though, and slip/ Into my bosom and be lost in me.”

Most singers know Roger Quilter’s setting of the text, but Britten’s is far more seductive, I think. It uses string orchestra and horn, and was originally written to be part of Serenade. Britten tucked this song into a drawer, and it wasn’t heard until 1987, according to the CD notes.

You can find out more about this album, which deserves a booby prize for ugliest cover ever, here.

Here is a promotional video for the album:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019