Dubliners were the first to hear Handel’s Messiah during Passion Week, 1742. Accounts of its premiere on April 13 treat it as the finest piece of music ever written. The only one to disagree? Librettist Charles Jennens.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

In this Toronto Messiah Climax Week — see details below — I thought it would be fun to look at the oratorio’s early days with the help of Donald Burrows’ 1991 guide to Messiah, published by Cambridge Unversity Press.

Jennens, scion of an iron-wealthy Warwickshire family, is a central figure.

By the mid-1730s, Londoners were no longer interested in Italian-style opera, leaving George Frideric Handle looking for a way to adapt his penchant for heroic vocal canvases to something new: morality tales told in English.

Enter Charles Jennens.

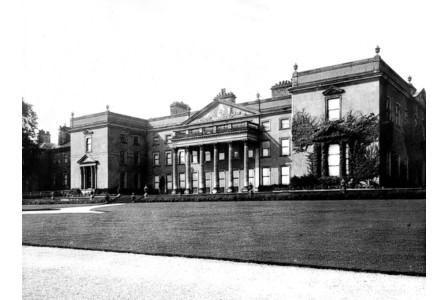

Jennens, a decade-and-a-half younger than Handel, spent the social season in London and summers at Gopsall, said to be the finest country house is Leicestershire (its last use was as an army headquarters during World War II, and was in such bad repair that it was demolished in 1951).

Jennens was one of a number of Britons who remained loyal to the Stuart succession and refused to swear allegiance to the Hanover kings, barring him from any sort of public office.

Instead of public service, Jennens occupied himself in the arts, indulging a deep interest in Shakespeare as well as music. He is said to have owned the first piano in England.

The devout Anglican (most of his fellow refuseniks — known as “non-jurors” — were Roman Catholics or Quakers) was also a huge fan of Handel’s, and began sending him librettos for oratorios in 1735, in hopes that they might summon a musical muse or two.

Burrows claims that the first recorded association of Jennens’ name with Handel shows up on a 1725 subscription list for the opera Rodelinda. Jennens would have been 25 years old.

In July, 1735 Handel wrote a note to Jennens letting him know that a copy of his opera Alcina will be on its way soon. The composer, whose opera company was in dire financial shape, also thanksed the younger man for the text to a new oratorio.

Handel’s first setting of a Jennens Biblical story was Saul, premiered in 1739. For Handel’s next season, the scholar reworked two poems by John Milton into the “pastoral ode” L’Allegro, il penseroso ed il moderato.

According to Burrows, Handel and Jennens left a trail of letters showing a happy collaboration as composer suggested changes to the text to suit his musical settings.

But Handel didn’t consult his librettist during the composition of Messiah. Perhaps he didn’t think it necessary, because Jennens’ libretto is essentially a collection of short verses from the Old and New Testaments. Its genius is in choice and the order, not in the words themselves, which came straight from the King James version of the Bible.

The narrative arc for Messiah represents the core of Christian faith: God’s Old Testament promise of redemption, the New Testament birth of Jesus, his condemnation, death and resurrection on behalf of all believers. It is a story that best fits the church calendar around Easter, not Christmastime.

Jennens wrote to his friend Edward Holdsworth in July, 1741 of sending the Messiah libretto off to Handel: “I hope he will lay out his whole Genius & Skill upon it, that the Composition may excell all his former Compositions, as the Subject excells every other Subject.”

Handel noted that he completed a clean draft of Part One of Messiah on August 28, Part Two on Sept. 6, Part Three six days later and the full orchestration on Sept. 14. (He went on to write his oratorio Samson over the course of the next six weeks.)

Needing to get away from London for a bit, Handel organized a series of subscription performances in Dublin that winter, culminating with a charity performance of Messiah featuring two cathedral choirs. Here’s the published account of the premiere from the Dublin Journal:

On Tuesday last [13 April] Mr. Handel’s Grand Oratorio, The Messiah, was performed at the New Musick-Hall in Fishamble-street, the best Judges allowed it to be the most finished piece of Musick. Words are wanting to express the exquisite Delight it afforded to the admiring crouded Audience. The Sublime, the Grand, the Tender, adapted to the most elevated, majestick and moving Words, conspired to transport and charm the ravished Heart and Ear. It is but Justice to Mr/ Handel, that the World should know, he generously have the Money arising from this Grand Performance, to be equally shared by the Society for relieving Prisoners, the Charitable Infirmary, and Mercer’s Hospital…

But when Jennens saw his first manuscript of Messiah a few months later, he wasn’t impressed.

He wrote to Holdsworth in January, 1743: “His Messiah has disappointed me, being set in great haste, tho’ he said he would be a year about it, & make it the best of his Compositions. I shall put no more Sacred Words into his hands, to be thus abus’d.”

Handel inadvertently added insult to the ever-proud Jennens’ injury by starting off his London subscription concerts the following month with Samson instead of Messiah. The latter didn’t get its Covent Garden premiere until March.

In February, Jennens grumbled to Holdsworth: “As to the Messiah, ’tis still in his power by retouching the weak parts to make it fit for a publick performance; & I have said a great deal to him on the Subject; but he is so lazy and obstinate, that I much doubt the Effect.”

Further complicating Messiah‘s London premiere was a fuss about whether it was appropriate to present such a religious work in a public theatre. To calm those waters, the composer dropped the title, referring generically to the work as a “New Sacred Oratorio.”

Jennens’ pestering caused Handel to finally re-set a handful of arias and choruses for two repeat performances at Covent Garden in April, 1745, and the two men appear to have resumed a broader working relationship — and further conflict — with Belshazzar, which had its premiere before that season’s Messiah performance.

Handel put Messiah away in a drawer until 1749. But the annual performances of the work didn’t take on the form of a tradition until the the 1750s, when the one-night London concerts were presented as charity fundraisers for the Foundling Hospital in London.

Handel conducted his final benefit performance of Messiah on April 6, 1759. He was blind, ill, and died eight days later. But his great oratorio would live on, figuring prominently in a series of concerts at Westminster Abbey marking the 25th anniversary of his death in 1784.

Meanwhile, after further disagreements with Handel over Belshazzar, Jennens turned his attention to Shakespeare, publishing new editions of King Lear, Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello and Julius Caesar before his death in 1773. The wealthy Jennens was regarded as a dilettante by other Shakespeare scholars — people he snippily described as a collection of dusty “old antiquaries” — and was never able to share the same limelight as other great librettists such as Metastasio or Lorenzo da Ponte.

Thanks to colonial migration and trade, performances of Messiah spread quickly through the British Empire. Excerpts were performed in New York City as early as 1770.

I would love to know when the first performance would have taken place in the Town of York. Given Toronto’s heavily British roots and good church choirs, it must have happened around the time York was officially established in 1793.

TORONTO’S FOUR MESSIAHS OF NOTE THIS WEEK

There are four very different, big-label Messiahs worthy of our attention:

- The Toronto Symphony Orchestra offers five performances at Roy Thomson Hall, starting Tuesday. They feature a small ensemble of modern instruments played in Baroque style, joined by 140 members of the Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, four fabulous soloists — soprano Yulia Van Doren, countertenor Daniel Taylor, tenor Michael Schade and baritone Russell Braun — and conductor Nicholas McGegan, whose last Messiah visit about a half-dozen seasons ago left a good impression. Details here.

- Tafelmusik Orchestra and Chamber Choir offers four performances at Koerner Hall, starting Wednesday. All are sold out. The one remaining opportunity to hear the period-instrument version complete with conductor Ivars Taurins dressed up as Handel is the Singalong Messiah at Massey Hall on Sunday afternoon. Details here.

- The GTA’s great sleeper orchestra, the Ontario Philharmonic, presents a single-performance, m0dern-instrument version at Christ Church, Deer Park on Friday evening with the Amadeus Choir. I’ll have more on this concert soon. Details here.

- Aradia Ensemble, led by founding artistic director Kevin Mallon, honours its own tradition of presenting the 1742 Dublin Messiah at the Glenn Gould Studio, so you can hear for yourself what got Jennens’ breeches all in a twist. Mallon has assembled excellent soloists: soprano Claire de Seevigné, mezzo Marion Newman, tenor David Menzies and baritone Peter McGillivray. And even regular-priced tickets are but $35. Details here.

+++

Here’s a little bit of trivia: The words to the Anglican hymn “Rejoice, the Lord is King” are by Charles Wesley and the music is by Handel. The tune is named Gopsal, a nod to Jennens’ occasional country hospitality — and the moments of inspiration Handel must have found in the temple, the ruins of which still stand on the former grounds.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019