It is probably no coincidence that Elizabeth Bishop wanted to be a musician or composer but turned instead to poetry when she was overcome by stage fright. Both composers and poets work with ink on paper which, when touched by our eyes, release sounds conjuring invisible worlds made of colour, rhythm, impression and emotion.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

Canadian soprano Suzie LeBlanc is on a mission to reunite the real words with the possible music of Bishop’s universe. It’s a mission that has proven to be, like so many adventures, full of unexpected twists.

To prove a cliché true, the journey has been even more interesting than its eventual destination could possibly be.

LeBlanc is in Toronto on Friday to provide a taste of a project born of happenstance and fuelled by passion. She, composer Christos Hatzis, pianist-composer Dinuk Wijeratne, reader Eleanor Wachtel and host Tom Allen present the story of LeBlanc’s Elizabeth Bishop Legacy Recording project.

There will be words, video, recorded and live music presented in the intimate new community and performance space on the ground floor of Chalmers House, the home of the Canadian Music Centre, on St Joseph St, starting at 5:30 p.m. on Friday.

UPDATE: The event is sold-out.

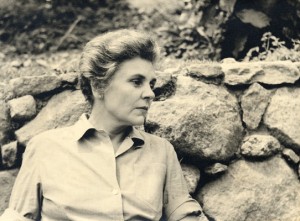

Essentially, LeBlanc commissioned several prominent Canadian composers to set poems by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), a Massachusetts-born poet who ended up living with her maternal grandparents in a village on Nova Scotia’s Fundy Shore at the right formative time in her childhood, leaving a lasting impression.

Bishop, whose father had left her enough money to live on for most of her adult life, travelled the world, but part of her spirit never left the Atlantic provinces.

For anyone unfamiliar with her poetry, it is a powerful mix of plain observation turned into powerful image and insight.

LeBlanc’s first encounter with Bishop came in 2008.

She was touring her Acadian album and her fellow musicians had booked themselves an extra gig in Great Village without LeBlanc. With time to kill, she strolled around the Nova Scotia hamlet and discovered an information pamphlet on Bishop inside the local church, which happens to be across the street from the house where she had lived.

“I thought, how uncanny is this that the Pulitzer Prize-winning, world-famous American poet grew up here. I had to know more about her,” LeBlanc recalls. She admits that she isn’t someone who avidly reads poetry. “But I suddenly needed to know more.”

The soprano was looking for a project to celebrate her 50th birthday. Bishop’s centenary was coming up in 2011. Prominent American composers (including Ned Rorem, Elliot Carter and John Harbison) had set Bishop’s verses to music but Canadians hadn’t. Things started to take shape in LeBlanc’s imagination.

She discovered that the poet had been an avid musician. “She carried a clavichord around for 40 years and took lessons,” LeBlanc notes. Bishop loved Gesualdo, Monteverdi and Anton Webern. Early Music was a particular passion — as it has been for LeBlanc.

The singer ran across a still-unedited diary chronicling Bishop’s walking adventures along Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula and had to do it, as well.

“I read it and thought, that’s it, I need to go exactly and retrace her footsteps and, while I’m doing it, read the poetry to let it sink in and find the pieces that will resonate with me and the composers and start building the programme,” recalls LeBlanc of the observations of a 21-year-old Bishop, gathered in the summer of 1932 as she combed the Rock with a friend.

LeBlanc invited along a visual-artist she had met during a residency at Mt Allison University in New Brunswick, and the resulting 50-minute documentary should be ready early in the new year. Together, they even sat down with some of the descendants of people Bishop had met along the way.

Finding the right path was sometimes difficult, as former dirt roads had become highways unsuitable for foot traffic, and now-abandoned roads were disappearing back into the earth.

One particular trajectory had been reduced to a dirt path. Bridges had been washed out, so they waded through rivers with their packs and camera equipment. They had to navigate bogs using big logs.

“That day, we had no idea if we would make it back,” LeBlanc recalls. “As it turned out, were picked up by a boat. We couldn’t possibly have made it back on foot.”

The singer laughs. “There were times I was angry at Bishop,” she laughs. “I thought, my God, woman, why have I let you into my life!”

LeBlanc has not just let Bishop into her life, but embraced her wholeheartedly. She sold her house in Montreal and now lives in St Margarets Bay on Nova Scotia’s South Shore. She took out a mortgage on her new place so that she could help pay for the new songs — and is now trying to recover the substantial fees for commissioning composers, hiring musicians, making the recording and then, eventually, distributing it through crowdfunding.

LeBlanc has a blog associated with the Elizabeth Bishop Centenary that currently shows $9,671 raised towards a goal of $60,000.

This is a long way to go, but LeBlanc is heartened by how much more Nova Scotians are aware of Bishop and her poetry now –and her much broader musical work is only just getting underway.

+++

I’m not much of a poetry reader, either, but what I’ve seen of Bishop’s verse strikes me as particularly affecting.

Even though it is not one of the 11 poems chosen by LeBlanc for her project (Christos Hatzis and Alasdair MacLean have each set four, Emily Doolittle has set one and John Plant has set two) I want to present “First Death in Nova Scotia” as an example of the poet’s remarkable powers which, in this case, defy music:

In the cold, cold parlor

my mother laid out Arthur

beneath the chromographs:

Edward, Prince of Wales,

with Princess Alexandra,

and King George with Queen Mary.

Below them on the table

stood a stuffed loon

shot and stuffed by Uncle

Arthur, Arthur’s father.

Since Uncle Arthur fired

a bullet into him,

he hadn’t said a word.

He kept his own counsel

on his white, frozen lake,

the marble-topped table.

His breast was deep and white,

cold and caressable;

his eyes were red glass,

much to be desired.

“Come,” said my mother,

“Come and say good-bye

to your little cousin Arthur.”

I was lifted up and given

one lily of the valley

to put in Arthur’s hand.

Arthur’s coffin was

a little frosted cake,

and the red-eyed loon eyed it

from his white, frozen lake.

Arthur was very small.

He was all white, like a doll

that hadn’t been painted yet.

Jack Frost had started to paint him

the way he always painted

the Maple Leaf (Forever).

He had just begun on his hair,

a few red strokes, and then

Jack Frost had dropped the brush

and left him white, forever.

The gracious royal couples

were warm in red and ermine;

their feet were well wrapped up

in the ladies’ ermine trains.

They invited Arthur to be

the smallest page at court.

But how could Arthur go,

clutching his tiny lily,

with his eyes shut up so tight

and the roads deep in snow?

+++

Here is a video interpretation of Elizabeth Bishop’s late poem “One Art” by Magpie Productions, other people who have been inspired by the poet’s craft:

+++

And here is LeBlanc singing Plant’s 2009 setting of “Sandpiper” with clarinettist Mark Simons and pianist Robert Kortgaard at the Indian River Festival in Prince Edward Island:

The roaring alongside he takes for granted,

and that every so often the world is bound to shake.

He runs, he runs to the south, finical, awkward,

in a state of controlled panic, a student of Blake.

The beach hisses like fat. On his left, a sheet

of interrupting water comes and goes

and glazes over his dark and brittle feet.

He runs, he runs straight through it, watching his toes.

– Watching, rather, the spaces of sand between them

where (no detail too small) the Atlantic drains

rapidly backwards and downwards. As he runs,

he stares at the dragging grains.

The world is a mist. And then the world is

minute and vast and clear. The tide

is higher or lower. He couldn’t tell you which.

His beak is focussed; he is preoccupied,

looking for something, something, something.

Poor bird, he is obsessed!

The millions of grains are black, white, tan, and gray

mixed with quartz grains, rose and amethyst.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019