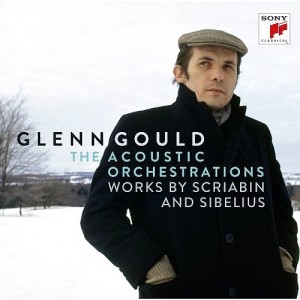

Yesterday, Sony Classical released something brand new by Glenn Gould, who will have been dead 30 years tomorrow: A studio performance of Alexander Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 5 recorded on four sets of microphones set at different distances from the piano strings.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

CBS Records (originally Columbia, now Sony) released the 1972 recording made in Toronto’s Eaton Auditorium (now The Carlu) as an ordinary stereo album in the mid-1980s. But Paul Théberge, a Carleton University professor of acoustic and recording technology, was determined to reassemble the music using a studio technique Gould called “acoustic orchestration.”

CBS Records (originally Columbia, now Sony) released the 1972 recording made in Toronto’s Eaton Auditorium (now The Carlu) as an ordinary stereo album in the mid-1980s. But Paul Théberge, a Carleton University professor of acoustic and recording technology, was determined to reassemble the music using a studio technique Gould called “acoustic orchestration.”

The piece had been captured on eight tracks, on four sets of microphones. In the editing suite, Gould and his engineers would mix and fade the different sound perspectives to create sort of an audio equivalent of close-ups and wide-angle shots of the music.

In one passage, our ears are glued to the tight, dry sound of hammer hitting string, whereas a few measures later, the notes are bathed in the reverberance of Eaton Auditorium.

I had dismissed these microphone techniques, which Gould had used elsewhere, as a distraction as well as a gimmick, much as the intrusive journeys inside the cast and orchestra of a Royal Opera House 3D opera broadcast.

But now that Théberge has explained what acoustic orchestration meant to Gould, I understand it less a gimmick and more a way to clarify the meaning of the music (at least in Gould’s mind, if not the listener’s ears).

Although all the tapes were there, Scriabin’s Sonata No. 5 had remained uncharted by a Gouldian acoustical plan.

During an interview, Théberge described the challenges of facing multiple takes of the same movement, each recorded on eight tracks, with no sketch of what Gould was looking for.

Undaunted by the question marks around this project, the academic received permission from Sony to let him work on it — and then convinced them that last week’s 80th birthday anniversary celebrations would be the perfect excuse to issue this album, which comes with a set of mix-your-own tracks, if you like tinkering with Garage Band, or similar audio-mixing software.

Théberge’s biggest revelation over the course of the project was how this sort of mixing addressed many of the challenges of both interpreting and listening to Scriabin’s music. He describes in detail how certain harmonies and contrapuntal passages benefit immensely from being captured from different sonic perspectives.

This may, in fact, be one of the least-known yet most provocative components of the Gould legacy.

The pianist was not just taking a machete through the interpretive jungle but actually perceiving recorded music in a new way, adding a further dimension to how we experience organized sound.

The vast majority of traditional classical musicians are locked in a static relationship with the product of the music they make: It is played here and heard there.

In a recording, the engineer sets the parameters of the overall sound and then the pianist or string quartet or orchestra and conductor ensure that their interpretive ideas come out clearly within those parameters.

The recording technology we now have at our disposal is so much more sophisticated and easier to manipulate than it was 40 years ago, yet the vast majority of classical musicians have not stopped to ask themselves how it might be put to some sort of creative use.

The best possible illustration and explanation of what so fascinates Théberge is seeing Gould in action at the Eaton Auditorium and then in the editing suite with his engineers (the younger man is Lorne Tulk), on a set of Préludes by Scriabin in December, 1972.

We get to see Gould’s microphone “choreography” (as he calls it) for the first time after the 7-1/2 minute mark, and then on-the-fly mixing after then 9-minute mark. The footage was captured by Bruno Monsaingeon:

Another subject came up during my chat with Théberge: the vast differences in speed, dynamics and texture between each take of the music, adding a further layer of mystery to the puzzle of how to assemble the Scriabin sonata.

A conventional classical performer will learn a piece of music, perform it in public a few times to put the finishing touches on the shape of his or her interpretation and only then, once they feel comfortable with it, go into the studio to record it.

Once there, if there are multiple takes, it is to get tiny little details just right.

In Gould’s case, he lays down a half-dozen completely different versions of the same piece, then decides, after the fact, which version(s) to use.

Essentially, Gould turned the conventions of interpretation upside down — a process that, in the end, is invisible and inaudible to the person enjoying the album.

For those of you with the time to take in an example, here is Gould at work on the Sarabande and Bourées of the first English Suite by J.S. Bach:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019