Stratford Theatre Festival: Ransacking Troy, by Erin Shields, Jackie Maxwell, director. World Premiere. Cast: Maev Beaty, Helen Belay, Sarah Dodd, Ijeoma Emesowum, Caitlyn MacInnis, Yanna McIntosh, Marissa Orjalo, Irene Poole, Sara Topham. Tom Patterson Theatre, Stratford, ON. Continues to September 28, 2025. Tickets here.

Playwright Erin Shields’s observations through the silent eyes of the women of Greece and Troy as men burn the world, sets Director Jackie Maxwell a great place to raise the ever-burning questions since writing has existed: what is hope, and what is the real cost of reality that exalts, then destroys human faith?

This play is about the rise and death of hope in a time of war. It is also about the long struggle between the men who destroy, take, and burn the world to the ground, and their women who dream of a world that could be different, women who are forced to fight and cut through one another, women who are smashed, pillaged, and broken — after all that.

And, the eternal questions of: who is right? What is the right thing to do? Why do we build a world that works seamlessly to crush the individual with a neverending chain of sorrows?

The Play

Starting from total darkness, to a stage bathed in blue and dark lights, the women of Greece gather to discuss the absence of men. Clytemnestra, a mother whose child was murdered by her own husband, Agamemnon, to launch the war, has become a fury herself through unspeakable loss. Penelope, known as the faithful wife of Odysseus through the mouths of men — sacrificing, ever-patient — gets to speak her true heart as a woman as she praises and bemoans Greece without men with her court of women: the orderliness, lowered crime and violence, the courage that women took to return society to functionality, just as women did in times of World Wars and all the other wars.

The unspoken tradition that fueled the world during the time where fire burns and the darkened blood of men and boys stains fields and cities.

However, war also brings another level of suffering for the women as they become tools of the war: the enslaved, the grieving, the taken women who face the violence of objectification and commodification by their new male ‘owners,’ with endless violence against their minds and bodies.

The absence of men also made their society unable to sustain itself — vulturing, cunning outsider men fill the courts, ready to snap up these courageous, compatible women, as soon as their husbands die. The young women are without suitable, righteous men to learn their essential craft to become a fully grown woman, from courtship, to love — love that goes beyond man and woman, but love that creates families, communities, and shared joy through the generations. Their states became stunted, as the curse of greedy, selfish, lesser men starts to infiltrate their world.

So the women crew sails to Troy, hoping to stop the war through coalition with the women of Troy, in an abandoned ship — too broken and undeserving of the valiant men who left as soon as the wind changed, who could not leave home too soon in search of glory — to capture and return with a promised woman, Helen, wife of Menelaus, the Spartan King, abducted by Paris, prince of Troy.

Creating New Stories From Old

Shields’ interest on creating new narratives from familiar old stories — this time, based on the Iliad and the Odyssey, makes this play all very entertaining, with ugly beards and much scrotum-scratching, as women pose as men.

The gentle love interests between the young, and the generational wisdom taught and transferred through these women highlights the strength of womens’ relationships. The individual characters are well-portrayed, though the general playfulness makes us want a little more of acrimony and bitterness when the humour turns dark.

The dreams and hope of these women, however, after a cut-throat scene between Helen and Clytemnestra, and another painful scene with Hecuba, the queen of Troy — the women from the other side, the black mirror — are shattered and broken, leaving them no other choice than abandonment, more death and questions for the future.

Reality Check

With the muted desperation that comes with further enlightenment and reality checks — this time, dark and foreboding — Clytemnestra awaits her husband, Agamemnon, with black vengeance to make him pay with his blood for the death of Iphigenia, the most precious thing that she ever lost.

Penelope, the ‘good wife,’ resigns to her fate and awaits Odysseus and prepares a feast, while her niece, Hermione, decides to stay despite her feelings for Cur, an additional character portraying a capable, independent queer woman who remodeled the ship, hence making this women’ s journey a possibility, and resigns to her fate to become another pawn as Menelaus and Helen’s daughter.

A few returns to the ship — including young Elektra — heading back to Circe’s, a place that belongs to a powerful woman, ironically protected by gods and men’s games — through her banishment.

We are left with bitterness, post-hope. How can this world be changed? Can violence eliminate violence? What does it mean, to create a new world? Do we hope, in order to only realize that hope isn’t real?

The Production

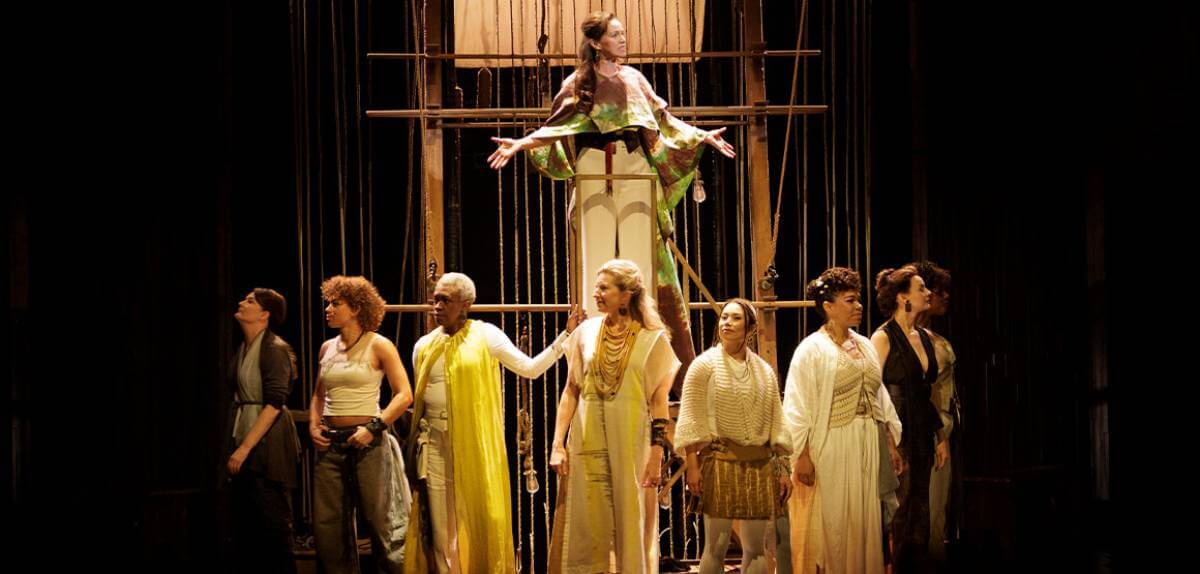

Judith Bowen’s set, made with a folding frame with ropes and weights that swing horizontally up to the ceiling from its initial vertical position, evokes ships with their many ropes and weights.

The rope, one of the simplest technologies, holds, binds, and connects things through distances, but as its softness — the core advantage — makes it impossible to be preserved, and hence often forgotten in the progress of technology and history, just like women, whose soft agileness and strength that binds the world, mostly remains unappreciated.

The entrance of Helen, after the intermission, as she descends to stage with a Hollywood glamour spotlight, was whimsical and evocative. However, the soft, feminine entry soon turns vicious, as Helen, a beauty, a prize, reveals the truth of her life, throwing it on the face of Clytemnestra.

Helen is loathed by women as they blame their suffering on men under her spellbinding beauty, as men fight, as they are fixated on her beauty — not to appreciate her beauty, but for the power that comes through the ownership of Helen.

This was another stunning point in the play where the minimal set and lighting successfully created the world of a desired woman in opulence, yet isolated and abandoned in the crowd, in that she is left by herself to defend with all her strength, against everyone, “… don’t judge me… for using the only currency I have.”

Here, Sara Topham was at her best, as she delivers Helen’s true sorrow, anguish and pain.

As the women of Troy land in Circe’s island, the frame shows itself as the magic loom of Circe, where history was recorded through her small, nimble fingers. This was a particularly poignant moment, as the ship, men’s domain, became a woman’s tool, a loom, that only Circe could operate; Circe, condemned to solitary banishment because she is intelligent and skilled, yet limited and bound to be a pawn in the endless games of men and gods.

Another stunning moment with softness that holds and binds, was when the women on their return journey arrived at the entrance of Hades. The blackness, spewing out from the hole, enraptures the women in state worse than death, as they run in desperate circles, their identities lost as their bodies are now enslaved in black fabric, stretching and covering them, and they scream the collective rage and loss of all the dead women of the war.

It was a fitting desperation — as women continue to grieve, beyond their death, through generational trauma and unspoken, yet resonating stories of loss so common in the time of war. Michael Walton (Lighting Designer), and Thomas Ryder Payne (Sound Designer)’s work with Bowden’s evocative sets, was stunning, especially in these three focal points.

Final Thoughts

The play portrays womanhood well — their softness, love for one another, collected anger against oppressors (as a feminist play, mostly men, and some gods and demi-gods); however, it is also undone by its gentleness.

The one-liner jokes and banter often resonated with men’s bullshitting sessions at mancaves and pubs. Whilst they are realistic, sensing the true rage and sarcasm embedded in women’ s daily lives, this made me wish for even more sardonic bitterness, and wilder humour.

The switch from elation to desperation — a downward slope throughout the second half as the women leave Troy, realizing the limitation and their unyielding fates through the eyes of men — was a great choice; it reflects the blinding futility and hopelessness that many of us still face in our own lives — especially if you are a woman.

The lack of false victory takes us further into the real question of the play: how do we convert passion and hope into actual changes in the real world, as we continue to live through, and in, wars?

The play is successful in raising today’s questions through ages-old epic. It is another voice that demands a look back to stories and histories that constitute our collective psyche.

Along with fictions redone with a feminist perspective: Madeline Miller’s Circe, and Pat Barker’s trilogy: The Silence of the Girls, The Women of Troy, and The Voyage Home, it is good to see the perspective off-the-page, and experience it through live performance.

The actresses do commit their best efforts, succeeding in empathic delivery of the rage and losses — especially by Maev Beaty, Irene Poole, Sara Topham, and Yanna McIntosh. But the questions raised around the cost of war, male-domination (or any domination without consent and cooperation), hit close to home; with its unclear and frustrating yet logical ending, the play successfully delivers the endmath of it all — of more questions and sufferings.

What could we do, and what do we do?

Are you looking to promote an event? Have a news tip? Need to know the best events happening this weekend? Send us a note.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig Van Toronto e-Blast! — local classical music and opera news straight to your inbox HERE.

- CRITIC’S PICKS | Classical Music Events You Absolutely Need To See This Week: January 26 – February 1 - January 26, 2026

- CRITIC’S PICKS | Classical Music Events You Absolutely Need To See This Week: January 19 – January 24 - January 19, 2026

- SCRUTINY | Champions Of Magic: A Return To A True Sense Of Wonder - January 5, 2026