Inuk film maker Zacharias Kunuk made a long awaited return to the Toronto International Film Festival in 2025 with a new work. His film Uiksaringitara (Wrong Husband) was screened for its North American premiere at the Festival.

He returns to a far north setting to tell a story about young lovers separated in a world where the natural and the supernatural live side by side.

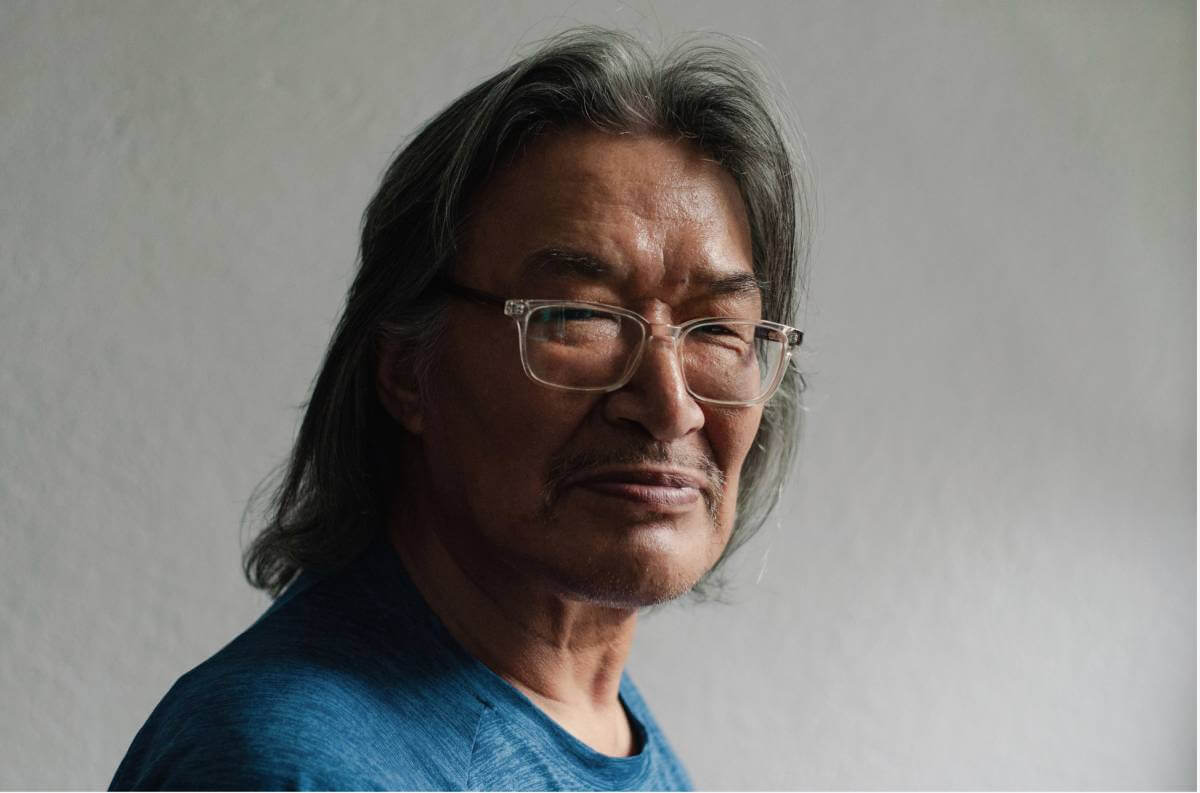

Zacharias Kunuk

Born in 1957 in a sod house at Kapuivik, an arctic island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of what is now Nunavut, film maker Zacharias Kunuk was sent to school in the town of Igloolik at the behest of the government. He and his brother were separated from their parents, who stayed on the land.

He began to learn English, and devised a plan of making soapstone sculptures to sell in order to get into the movies that screened at the local Community Hall.

For four millennia, the people of his region had used oral storytelling as their method of preserving history without a written language.

Kunuk credits the experience of watching the Hollywood movies of his era, including the cowboys vs. Indians dramas common at the time, with insights he gleaned about how stories could be told from different sides.

He came to realize that producing film and television locally in Nunavut would strengthen ties to Inuit culture in a society that was still healing from colonialism., and has become a pioneer of film making in the north.

Today, he’s perhaps best known outside of that region for his 2001 epic film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (Inuktitut: ᐊᑕᓈᕐᔪᐊᑦ), which was the very first feature that was written, directed and acted entirely in Inuktitut. It premiered at the 54th Cannes Film Festival, and went on to win the Caméra d’Or (Golden Camera), along with six Genie Awards back home in Canada. Fast Runner was the highest grossing Canadian film of 2002.

Uiksaringitara (Wrong Husband) a film by Zacharias Kunuk

In Uiksaringitara (Wrong Husband), Kunuk weaves the supernatural and the mundane into a story with larger themes that could take place anywhere.

Shot in Igloolik with a largely non-professional cast, the dialogue is in Inuktitut. It’s set about 4,000 years ago.

The landscape plays its own role in the story, a realm of snow and ice and grey rocks, of infinite variations in shades of white and grey and blue — a place where it’s very easy to believe that magic and otherworldly elements hide around every corner. Cinematographers Jonathan Frantz and Thomas Leblanc-Murray nicely capture the multitude of qualities in the ever changing landscape from simply arresting and expansive to haunting and spooky.

As the story opens, a troll hides in the shallow pools of water that open up when the ice surfaces begin to melt. He snatches up children from the nearby town when they stray too far away.

As children, Kaujak (Theresia Kappianaq) and Sapa (Haiden Angutimarik) are promised to each other, and it’s a promise they are both still eager to keep as they grow up. They are in love, and looking forward to a coming marriage.

But, then tragedy strikes. Amaujak, the patriarch of Kaujak’s once happy family, dies, and it leaves the fatherless clan vulnerable.

A stranger comes to town not long after, and it so happens he’s looking for a wife. By agreement with the remaining elders of the village, the newcomer Makpa (Mark Taqqaugaq) takes Kaujak and her mother, Nujatut (Leah Panimera), to another village at a moment’s notice. Unhappily, Kaujak follows the new couple away from the place she calls home.

At the new village, new suitors swarm around Kaujak.

“They’re trying to marry me to the wrong husband!” she cries.

Two shamans are manipulating the story from the sidelines, and the death of Amaujak is more complicated than it first appears. The moon is revealed as the protector of children and abused women.

And, the troll still lurks just beyond the houses of the small town. Traditional percussion and vocal music add to the atmosphere of the film, and evoke the magical elements in the story.

“Sometimes, life reminds us that we are powerless.”

The plight of unhappily married women is a strong theme that runs throughout the story. Will Sapa be able to free Kaujak from the wrong husband?

The Setting

Kunuk’s previous work has been praised for its verité realism, and the new film is no different. He depicts the processes of treating animal carcasses and hides, so integral to Inuit culture, in detail.

The technology possessed by the Inuit people includes the tools needed for refined sewing, elaborate clothing designs and intricate beading, eye protection from the snow and the sun, among many other things. It is a society of no waste, where animals are consumed in every way possible.

Thousands of years ago, the Inuit carved out an elaborate society in the midst of a frozen landscape.

Zacharias Kunuk: The Interview

“I was looking for good stories,” Kunuk begins.

He relates that years ago, in the mid-1960s, he met a man who lived in Igloolik, and who had, as in the story, married a woman who had been promised to someone else.

“I heard about this fight,” he says. “The wrong husband lost, and he took her away.”

That became the kernel of the story that he developed for the film and set in an ancient time. Into it, he wove the mythological elements of Inuit tradition, like the troll. It came from a story that was told to him by his mother, a cautionary tale.

“We never see the troll,” he recalled. “We only hear about him.” it didn’t stop mothers from using the creature as a deterrent.

When he wanted to add it to the film, Zacharias had to come up with an idea of how it would look. “When I’m trying to develop this monster, I talked to elders,” Kunuk says. “Not many people have seen them.”

From that consultation came the idea of an ugly creature with a big nose. It’s effective as a kind of semi-aquatic, menacing element in the film.

Two shamans were also woven into the story. “I heard about shamans before we got bulldozed by Christianity,” he says. When he was separated from his parents, at school, he was forbidden from practicing traditional culture in any form. “But, we’re bad people, we break all the rules,” he laughs.

“It’s fun making this kind of film.” He also enjoyed the special effects that were created to depict the magic that flows, particularly in the scene with the two shamans. “I wanted that scene to be out of this world.”

The Promise

The promise made by the two mothers in the beginning of the film was an important element to set up in the film.

“In this oral culture, you don’t have a pencil and paper to make a contract,” he says. An oral promise was a solid one. “You don’t break promises.”

The film illustrates other aspects of the culture, like the popularity of nicknames. One of the other townspeople is called a “Wifeless Buddy” in a touch of Kunuk’s characteristic humour, and Kaujuk calls her mother “Younger Sister”. That stems from another tradition, as Kunuk explains.

It’s a system of inheriting names from relatives who’ve passed. In the present, your living relatives call you by the older person’s name, and relationship.

“To keep the name alive,” he explains. “Me, when I was growing up, my father called me “Mother”,” he says. He’d been named after his maternal grandmother. “I inherited five names.”

It’s a film that preserves an ancient and unique culture with universal themes about love and liberty, while not shying from its difficulties.

“In this culture, it’s a man’s world, but women have a say in it,” Zacharias says.

Hopefully, the film will soon find a streaming service so more people can enjoy this atmospheric story.

Are you looking to promote an event? Have a news tip? Need to know the best events happening this weekend? Send us a note.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig Van Toronto e-Blast! — local classical music and opera news straight to your inbox HERE.

- PREVIEW | Kindred Spirits Orchestra Presents Operatic Rhapsodies February 7 - January 28, 2026

- INTERVIEW | Music Director Martin MacDonald & Violinist Stephen Sitarski Talk About Cathedral Bluffs & Romeo And Juliet - January 28, 2026

- THE SCOOP | Toronto Musicians And Composers Recognized By Six JUNO Nominations For 2026 - January 27, 2026