Peter Ottmann, 67, is retiring after an astonishing 48 years with the National Ballet — first as a dancer, then choreologist, and later as senior répétiteur.

His public swan song will be appearing on stage in the title role of the National’s new production of Don Quixote, choreographed by Cuban-born superstar Carlos Acosta. The ballet runs June 1 to 9 at the Four Seasons Centre.

What follows is my interview with Ottmann as he talks about his life and times, which also gives us a glimpse into behind the scenes at the National. He proved to be thoughtful, clear-sighted, and most of all, candid. We met over Zoom during Ottmann’s hurried lunch break between rehearsals.

There is also an end note about this new Don Q (as it’s called in the trade.)

First of all, we should explain exactly what a répétiteur does. At the National, I believe, the term is interchangeable with ballet master.

We learn all the choreography of a piece so we can rehearse it, reproduce it, and stage it. In the case of historic ballets with set pieces, we coach the dancers. We also assist a choreographer with new creations. There is a very set formula for success. I learned my craft from our former ballet mistress, the great Magdalena Popa, who coached me as a dancer, and then coached me as a coach. Occasionally I appear on stage in character roles — sort of the senior citizens of ballet.

Now, you are retiring after 48 years with the company.

It turned out to be a mutual decision. I had already decided that this was going to be my last year, but as it happens, so did artistic director Hope Muir. She’s planning to bring in a lot of new choreography, so she needs a staff for the long term — people who will become familiar with the new repertoire, and if I stayed, my time would be limited. We had a good meeting.

Your last stage appearance will be in the title role of Don Quixote in the new production.

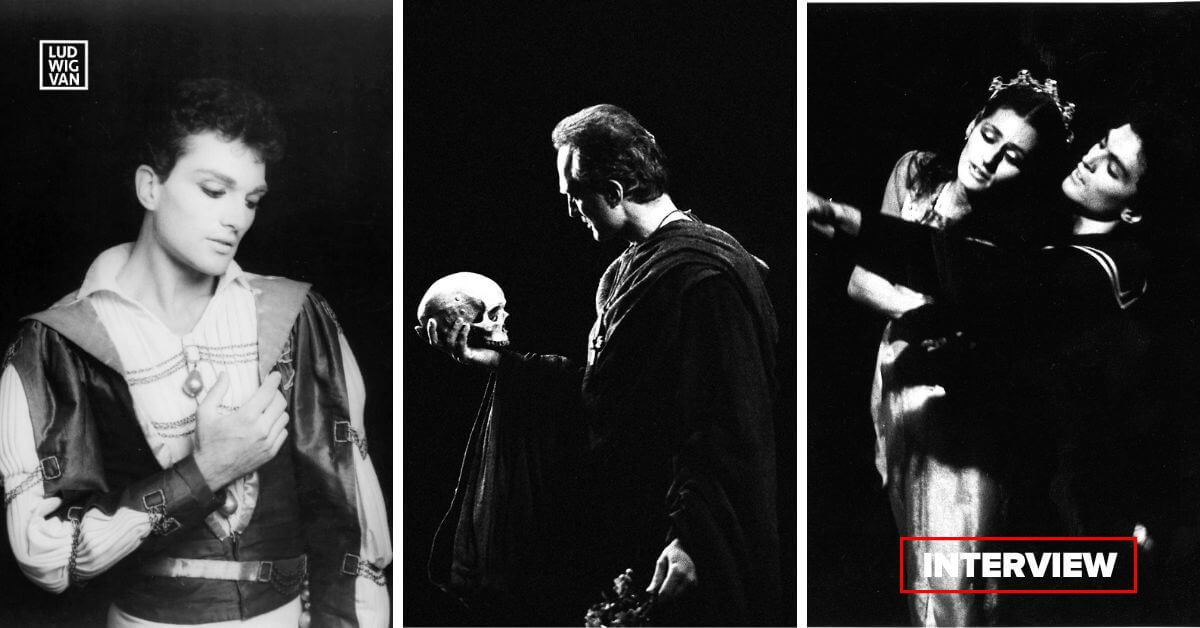

That was a big surprise, because I have never done the role before. I thought that my last stage appearance was going to be playing both Friar Lawrence and the Duke in last year’s Romeo and Juliet. It’s exciting taking on a new role.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Where were you born?

My parents immigrated from London, England and came first to Montreal, then Renfrew, Ontario, and finally settled in Kitchener. An older sibling was born in London, me in Renfrew, and the last three in Kitchener. We’re five altogether.

Did you grow up in an artsy home?

Yes. My dad was an electrical engineer who was also sporty — he played cricket and was a boxer, but he was also a singer. My parents loved the arts. In London, they had seats at Covent Garden. They insisted that their children had to experience different disciplines, so I learned the oboe and piano as my instrumental art, choir for singing, and ballet for dance.

Is that how you got into dance?

Jill Officer, who later became a professor of dance at the University of Waterloo, was my ballet teacher. I remember that her studio in Kitchener was above some shops. I started with her when I was four, and when I was nine, she suggested that I audition for the National Ballet School in Toronto. There were 120 girls who auditioned and 35 boys. Needless to say, they snapped me up. As a boy, you had to be willing to wear tights, and I have always hated that. Thank goodness that the unitard came along.

There were fun times at the school, though. One Halloween, we knocked on Betty Oliphant’s door at her house in Cabbagetown. That was pretty daring because she was head of the school. She actually invited us in and served us cheese and crackers.

I know your brother John Ottmann has had a career in dance. What about your other siblings?

Mary studied theatre at Ryerson and Joseph is a sculptor and painter. John and his wife are currently running a dance school in China.

So after the ballet school, did you enter the National?

That was the usual route, but I felt that my body still had to mature, so to extend my studies, I got a Canada Council grant to go to Europe for a year, where I joined company class at various ballet companies. Wherever I went, they would say, “You’re from Canada.” They knew Betty Oliphant’s National Ballet School style. After Europe, I finished the year with more training at the ballet school.

So then you joined the National?

Yes I did, in 1976. Artistic director Alexander Grant and I joined together.

In truth, I had had a long relationship with the company, playing pages in Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty. I was part of the court in Giselle, and I followed Rosalind in Romeo and Juliet. The dancers all knew me.

For example, one of the companies I took class with in Europe was Roland Petit’s Ballet de Marseille where Karen Kain was a guest star. When she saw me, she grabbed me and gave me a big hug, saying how homesick she was for Canada.

But your first years were rocky.

I had injuries in the beginning, and I couldn’t go on tour. There were no health measures in place in the company at the time. I had to find my own chiropractor to act as a sports therapist.

Later, when I became the equity rep on the board, representing the dancers, I stressed the need for a sports doctor because dancers are athletes, and a valuable resource. No one should have to go through what I went through with my injuries. The sports therapy staff is now a standard part at the company.

Let’s talk about your dance career.

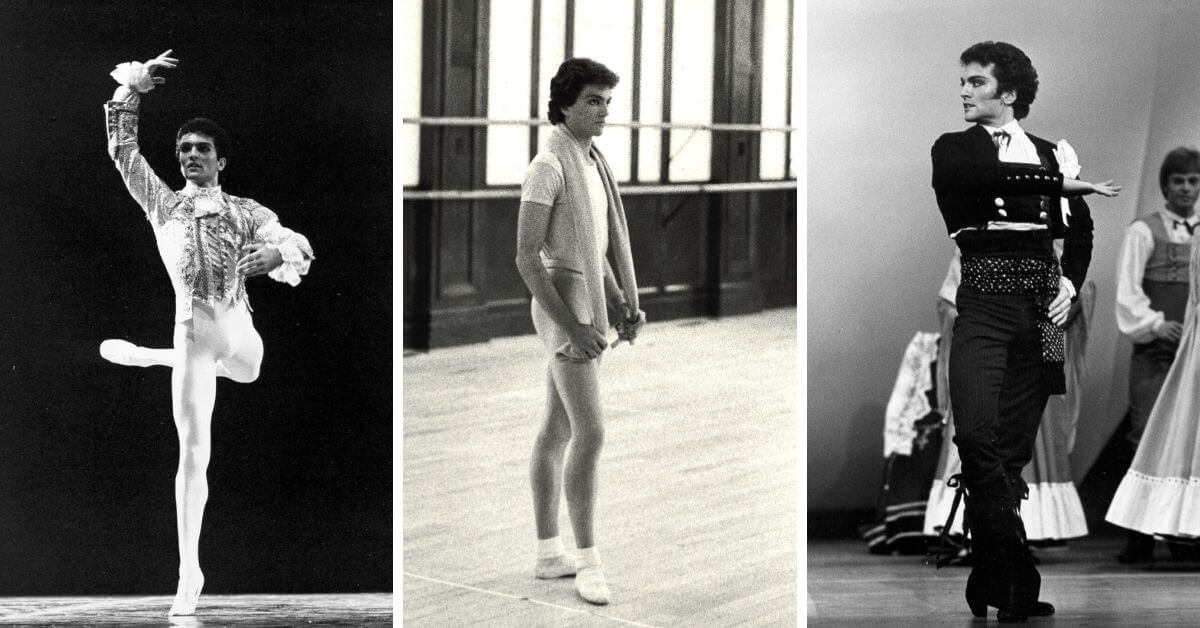

I was promoted to second soloist in 1979, and first soloist in 1983. I did perform principal roles in La Sylphide and Romeo and Juliet, which was my favourite, and in works created for me like Glen Tetley’s Alice and La Ronde, William Forsythe’s The Second Detail, and James Kudelka’s Musings.

But you never made it to principal.

I understood my shortcomings. Although I was a good partner, I lacked technical prowess. I was not a huge jumper or a showy trickster.

Then Eric Bruhn took over from Alexander in 1983, and he was inspiring, amazing, challenging and frightening. He would stroke you with one hand, and smack you on the head with the other. He also understood me as a dancer. He told me that I needed ballets with substance, rather than technique, and so he gave me Albrecht in Giselle. His motto was to push you forward, and not leave you where he found you. James Kudelka was like that too when he was artistic director.

So let’s talk about your change of career, from dancer to behind the scenes.

I transitioned in 1993 after 17 years as a dancer. When I got married, dancing became a hard slog. We wanted children, yet after dancing an exhausting role like Romeo, how was I going to have the strength to come home and change diapers? I had had a great experience as a dancer with both the repertoire roles I got to perform, and the roles that had been created for me, but it was time for a change.

At that time, Reid Anderson was artistic director, and he noticed something about me. For example, the questions I asked Billy Forsythe when he was setting Second Detail about the count. Do we count as music, or as an independent count? I would also correct my fellow dancers if they were doing their solos wrong. I seemed to really understood the relationship between dance and music.

So Reid talked to me about becoming a choreologist, which is a person who notates dance, and that took me to Benesh International in London, England in 1993 to study Benesh Movement Notation. Reid told me that there would be a job waiting for me when I got back. He also told me that the work was intense and time-consuming.

What’s involved in Benesh notation?

Rudolf Benesh was a mathematician and a musician, and his wife Joan was a dancer at the Royal Ballet. They established a way of recording human movement in 1956.

What if Beethoven couldn’t write down the 9th symphony as music notes? How could he pull it together? The Beneshes reasoned that the same thing was true about dance, where you only had memory and the oral tradition. Their notation system accounts for every physical movement aligned with every note of music. You can also add in extra information like a flex wrist here, or a turned knee there.

What were some of your new responsibilities in 1994?

My title was choreologist and ballet master. At first I notated dance, but I moved into setting ballets, rehearsing them, casting them, and coaching soloists. I managed a large part of the classical repertoire, and a lot of the contemporary pieces.

When James Kudelka became artistic director in 1996, he made me assistant to the artistic director. In 2005, Karen Kain appointed me senior ballet master, and Hope Muir made me senior répétiteur in 2022.

Every time I was in the studio with James, I learned something. For example, I assisted James when he was creating The Nutcracker in 1995, and so I would use his words when talking to the dancers when we remounted the piece each year.

I see the job of ballet master/ répétiteur as one that requires integrity, as well as being cooperative and helpful. My task is to impart difficult choreography without everyone crying.

Staging dances on other companies is a singular honour.

Glen Tetley was the first choreographer to trust me to set his work. It was Voluntaries that he had created for the National in 1989. James Kudelka has also used me. It’s important that nothing be changed, because everything in the piece is meaningful.

Do you see a future role with the National?

We’ve talked about performing character roles, and setting ballets. On my wish list is notating all the ballets of James Kudelka.

Any final thoughts?

I’ve been blessed in my career. It has been an embarrassment of riches, performing the smallest child to an elderly eccentric.

End Note: On the new production of Don Quixote

Marius Petipa created the Russian classical ballet Don Quixote in 1869 to music by Ludwig Minkus, and revived it in 1871. Over the years, there have been many alterations.

In his day, Cuban-born Carlos Acosta was considered one of the greatest danseur nobles of his generation. He first staged Don Quixote in 2013 for Royal Ballet, and redid the work in 2022 for Birmingham Royal Ballet where he is now artistic director.

The new iteration better accommodates touring, and serves as a signature work for the company. New features include lavish new sets and costumes, the use of voice, projections, and a new orchestration by Belgian composer Hans Vercauteren, and of course, what one critic called “smouldering choreography”. Clearly a great dancer is going to go for technique on steroids. There is even new music for guitar.

From Hope Muir, “Carlos staged this version of Don Quixote for Birmingham Royal Ballet in 2022, bringing his wonderful sense of story to an exquisite design and new orchestration of Ludwig Minkus’ score. Don Quixote is always a joyful ballet but this version feels particularly true to Carlos’ unique energy and passion as a world-renowned artist. I have known Carlos since we were young artists together at English National Ballet and his international career as a performer, choreographer and now Artistic Director of Birmingham Royal Ballet is legendary. I am thrilled for our dancers and audiences to experience this production.”

From Peter Ottmann, who is performing Don Quixote, “While many choreographic elements and scenes are the same, the choreographic style is new reflecting Acosta’s Cuban background and his career as a dancer in England. It’s Cuba meets England meet Russia.

“Acosta has enriched the role of Don Q and it’s wonderful to perform. He’s a refined, eccentric dreamer who lives in his ideals and just wants to save the world. It’s very poignant. His Don Q is still very classical, but the whole ballet looks fresh and different, and is very entertaining.”

Are you looking to promote an event? Have a news tip? Need to know the best events happening this weekend? Send us a note.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig Van Toronto e-Blast! — local classical music and opera news straight to your inbox HERE.

- SCRUTINY | Mirvish’s Canadian & Juliet Is A Runaway Hit - December 16, 2025

- SCRUTINY | The Woman In Black Evokes Terror Without The Customary Digital Spectacle - December 10, 2025

- SCRUTINY | Performances And Dazzling Production Values Elevate Mirvish’s We Will Rock You - December 8, 2025