Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 (BR Klassik)

★★★★★

🎧 Presto

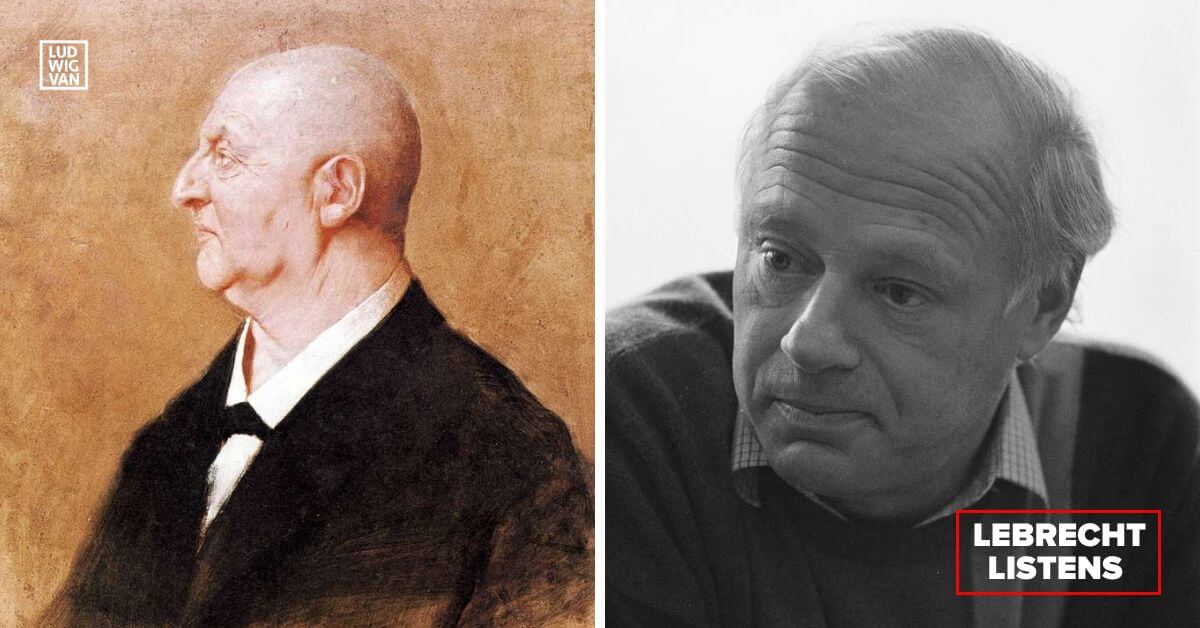

At the risk of provoking premature exasperation, I’m about to start the Bruckner bicentennial year a few days early. The Dutchman Bernard Haitink was a natural Brucknerian, more so than he was a Mahlerian. He had an innate grasp of structure and knew how to withhold passion and when to let rip. While Karajan, Wand and Giulini stole Bruckner’s thunder in the record stores, Haitink stuck to his meticulous ways with the symphonies, laying down markers for a longer posterity.

As principal conductor at the Concertgebouw, London Philharmonic, Covent Garden and Chicago, Haitink would make time for seasonal trips to Munich to work with the world’s best broadcast orchestra, the BRSO. Their sound in Bruckner is exemplary, the brass feral and unconstrained, the lower strings relishing the gift of a really big tune. The first page of the seventh symphony might well be the most impressive opening Bruckner ever wrote. The work was certainly the greatest success of his lifetime, coming shortly after he turned 60 and elevated by the Leipzig conductor Arthur Nikisch into a thing of wonder.

On the face of it, there is no imaginative leap forward from previous disappointments. The four movements look classical and sound romantic, but there is an authority that was hitherto absent. Richard Wagner had died since Bruckner last finished a score, and it is not far-fetched to suggest that the bereaved disciple stepped into the vacancy with a larger, more confident tread.

In an hour-long work, the first two movements take up 40 minutes can appear top-heavy. Haitink avoids the pitfall with a steady beat that is mitigated by lightness and touches of wit. This is the least Germanic interpretation you will find, the antithesis of folksy naiveties by Eugen Jochum, Gunter Wand and Karl Böhm. It is a reading that grows with repletion, vying with Karajan for explosiveness and with Giulini for sweet lyricism.

You will find no better entry point to Bruckner than this delicately civilised, never bombastic exploration of an essential milestone in German music.

To read more from Norman Lebrecht, subscribe to Slippedisc.com.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Two Releases Of Elgar Symphonies To Compare - April 19, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Jordan Bak’s Cantabile For Viola Reveals The Neglected Instrument’s Beauty - April 12, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS |David Robert Coleman & The Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Reveal The Charms Of Walter Kaufmann - April 5, 2024